Will Narendra Modi be India's Thatcher?

- Published

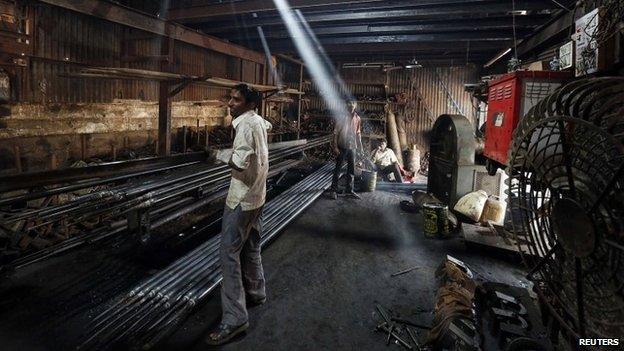

The government needs to improve India's appalling infrastructure

India's Narendra Modi-led BJP government will unveil its first full-year budget on Saturday. The budget is seen as a key test of Mr Modi's appetite for reform. The BBC's new South Asia correspondent, Justin Rowlatt, asks how far he is likely to go to stimulate growth and provide jobs.

Expectations are running high for the new government's first major budget.

The hundreds of millions of Indians whose votes helped sweep Prime Minister Modi to power in May last year believed that he offered the best hope for bringing growth and jobs to the country.

The budget will be the first really big test of Mr Modi's reformist credentials, an opportunity for his government to demonstrate how it intends to reshape the Indian economy and deliver prosperity in the years ahead.

So how radical will Mr Modi's government be: is he India's answer to Margaret Thatcher, ready to fundamentally restructure the economy?

Mr Modi has already identified India's key challenge: to create jobs. India's vast population should be a huge asset.

Almost half of its 1.25 billion people are under 25. Find them decent jobs and you create a powerful engine for prosperity and growth. This is India's potential "demographic dividend".

Yet hundreds of millions of Indians still live in abject poverty.

Shining success

Two-thirds of the country gets by on $1.50 (97p) a day or less, according to the Asian Development Bank; nine out of 10 Indians work outside the formal economy; and even more shockingly Unicef estimates that almost half of all Indian children are malnourished.

Mr Modi has said he aims to create the employment that would help lift people out of destitution by encouraging manufacturing industry to flourish - you see his invocation to "Make in India" everywhere.

And there are certainly some shining successes in manufacturing, as well as in the more commonly celebrated sectors of software and pharmaceuticals.

This week I visited Royal Enfield, the oldest motorcycle brand in the world.

Royal Enfield has blossomed under its Indian owners in recent years

This once British-owned business has blossomed under its Indian owners in recent years. In 2010 it sold 50,000 Royal Enfields, last year that was up to 300,000. It expects to sell almost half a million bikes this year.

It is, boasts Sidhartha Lal, the company's young and casually dressed chief executive, "the most profitable automotive business in the world".

Yet despite his company's success, he says India is still a very tough place to do business.

That view is confirmed by the World Bank, which produces an index measuring the ease of doing business around the world.

India is ranked a woeful 142nd out of 189 countries, behind beacons of good business practice like Yemen, Uzbekistan and Iran - vivid evidence of the scale of Mr Modi's challenge.

Mr Modi has said he wants to take India into the top 50, which is where the Thatcher comparison comes in. How far will the Indian prime minister be willing to go to streamline the Indian economy?

Unthinkable?

His critics say so far his government has been better at producing slogans than tackling real problems. They say he needs to take on India's trade unions and reform India's restrictive labour laws.

If he wants to do something really eye-catching he could begin to privatise some of the array of companies still owned by the Indian state.

He could start with Coal India, perhaps, or maybe the national airline, Air India.

The idea is as unthinkable to many Indians as it was to many British people when Mrs Thatcher proposed it but, say free market economists, it would mark Mr Modi out as really serious about reshaping the Indian economy.

Mr Modi's land acquisition bill is being opposed by farmers

If he's feeling really brave he could reform India's vast and heavily subsidised railway network - so big it warrants its own separate budget, presented two days before the main event.

At the very least, say his critics, this budget needs to give clear direction on how the government intends to improve India's appalling infrastructure.

They want to see a commitment to capital investment to improve the roads and efforts to guarantee reliable water and power supplies. According to one survey, half of all manufacturers suffered power cuts lasting five hours each week.

But the criticism of inaction isn't entirely fair.

Mr Modi's government is already attempting to replace the network of state taxes, a huge barrier to trade within the country, with a national goods and services tax - a very significant reform, if he can only get it passed.

The government is standing by plans to make land acquisition easier for businesses, despite considerable political heat.

It has also moved to ease foreign investment in Indian companies and is trying to cut back the thicket of bureaucracy that ties so much of Indian life up in knots.

Trimming subsidies

Nevertheless, those looking for dramatic reform on Saturday may well be disappointed.

Take India's vast food and fuel subsidy bill, something the Modi government has promised to trim.

Word is that Mr Modi's Finance Minister Arun Jaitley will announce he is slashing $8bn (£5.15bn) from the total, a 20% cut. That sounds like an impressive figure until you realise that most of this will come from falling fuel prices.

The budget will be the first really big test of Mr Modi's reformist credentials

That would be more evidence that the administration is keen to avoid dramatic confrontation.

"Why take on the unions when you'll just end up fighting them for the rest of your term," a senior Indian businessman told me Mr Modi had said to him.

And unlike Margaret Thatcher who came to power in the depths of recession, creating an urgent justification for structural reform, Mr Modi has a fair economic wind behind him.

Growth is slowing in China, has virtually stopped in Brazil, while Russia has gone into reverse. India, meanwhile, has been forging ahead.

According to the official figures the Indian economy grew at 7.5% in the last quarter of 2014. On that basis, India is already the fastest growing big economy in the world.

The figure may exaggerate India's achievements.

The Modi government has controversially recalculated the GDP figures to cast the country in a favourable light. Nevertheless, even Mr Modi's most ardent critics agree growth is well above 5%.

What's more, inflation is under control, the rupee has stabilised and the stock market is booming.

India will also be a huge beneficiary of the collapse in the oil price - 80% of the country's oil is imported.

But Mr Modi and Mr Jaitley would be unwise to rest back on the cushion of a buoyant Indian economy and avoid tough choices.

The country's youthful population presents the government with a unique opportunity.

If it succeeds in creating good jobs for the million new workers that come into the job market every month, it will entrench growth and set India on the path to prosperity.

But if it fails to do so India's demographic dividend could easily become a demographic disaster.

Hundreds of millions of Indians would remain trapped in poverty for decades to come, representing not just a legacy of misery but a brake on India's future growth.

- Published26 February 2015

- Published26 May 2014

- Published9 February 2015

- Published29 August 2014

- Published29 August 2014

- Published18 May 2014