Indian designers reinterpret traditional textile art

- Published

Rimzim Dadu and her colleagues are trying to reinterpret Indian textiles

Can it take two years to make a piece of traditional Indian garment sari?

The garment is the most popular women's wear in India and is sold in big and small shops across the country.

But Delhi-based fashion designer Rimzim Dadu took nearly two years to create her silicone Jamdani sari as part of an initiative to "reinvent" Indian textiles.

The Jamdani weaving tradition comes from the Bengal region in eastern India and Bangladesh. It is one of the most time and labour-intensive forms of handloom. Jamdani is a fine muslin cloth on which decorative motifs are woven on the loom, typically in grey and white.

But Ms Dadu used silicone sheets and cut them into fine threads to weave her Jamdani sari.

"Silicone is a very delicate and elastic material. I took long silicone rubber sheets, shredded them into very fine yarns and then hand-wove them into a Jamdani sari," she explains.

Her work is part of an ongoing exhibition called "Fracture: Indian textiles, new conversations" in a Delhi suburb. It seeks to redefine Indian craft for global and domestic audiences.

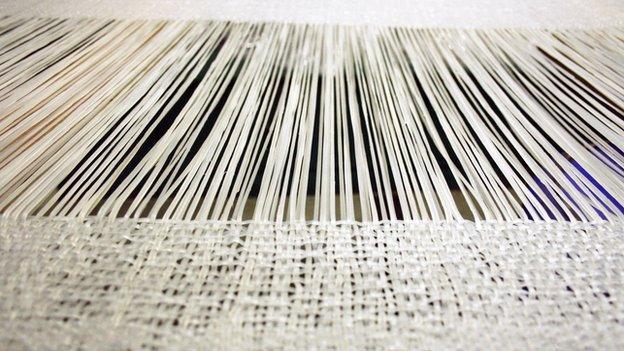

Silicone sheets were shredded into fine cords for the Jamdani sari

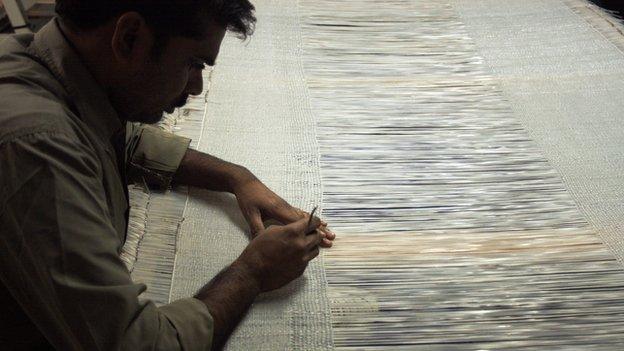

The entire sari has been hand woven

The sari is an outcome of two years of fine work and planning

'Fresh perspective'

Indian textiles are known and loved all over the world for their detail and craft.

The exhibit's message says that Indian textiles are unparalleled because of their extraordinary diversity in aesthetics and techniques. They straddle the multiple genres of arts, design and manufacturing.

Then why reinvent?

Ms Dadu says India has a brilliant heritage of textiles and craft "but felt the time was right to have a fresh perspective".

"The exhibit is about exploring our own potential and pushing our own boundaries. We are trying to find out what more can we do with our heritage," she adds.

Exhibition curator Mayank Mansingh Kaul agrees.

"There is a great sense of nostalgia about Indian textiles. But we wanted to find out what breaking away from traditions means," he says.

"We want to tell the world that India is just not a manufacturing hub for global brands, but it can emerge with its own innovations and compete with the world," he adds.

Swati Kalsi, another participating textile artist, has been practising the craft of Sujani for many years now.

Designer Swati Kalsi has reinvented the Sujani fabric

Sujani commonly refers to the traditional layering and sewing together of old worn fragments of cloth for soft wraps, quilts and mats, commonly practised in the eastern state of Bihar.

She has worked on reinventing the traditional Sujani fabric for the exhibition.

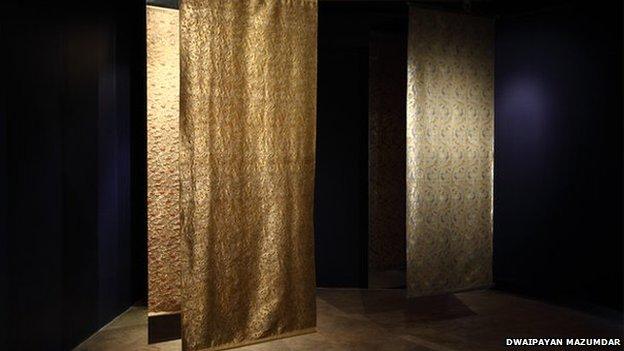

These panels by Rahul Jain reinterpret the traditional Varanasi brocade by highlighting India's vanishing wildlife

'New materials, old techniques'

Works by Ms Dadu, Ms Kalsi and other designers will also be presented later in the year at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London as part of an exhibition called Fabric of India, external.

Established Indian names such as Manish Arora and Rajesh Pratap Singh and emerging talents like Rahul Mishra, Aneeth Arora, and Kallol Datta will be part of the V&A exhibition.

Textile expert Divia Patel feels that reinvention of textiles is not a new phenomenon in India.

"If you look at the post-Independence period, writers like Pupal Jayakar and Mulk Raj Anand were talking about the need to re-invent textiles for new urban markets. At that time artists and designers like KG Subramanyan and Ritin Majumdhar were bought in to modernise textiles," she says.

She also adds that the work of today's designers is equally important.

"The work by Rimzim and other artists and designers is important because it opens up new ways of appreciating textile history and of inviting us to look at the process of making again."

She adds that reinvention "pushes us to think about new materials and old techniques".

"It pushes us to think about how familiar materials like leather are used in innovative ways while still paying homage to the textile traditions like patola," she says.

Ms Dadu reinterprets the traditional Patola weave from Gujarat state in leather which will be on display at the V&A museum

Ms Patel agrees that Indian designers are gaining more prominence globally because of such events. "They are celebrating something that is unique to India and which can be infinitely adaptable and desirable, as history has shown," she adds.

Weavers' future

But designers are not alone in India's quest to reinvent its textiles. Most artists and designers work with weavers from remote places.

Ms Dadu and Ms Patel hope that reinvention will help the people at the grassroots level.

"These initiatives are small but much-needed steps in the right direction. It's a long process but eventually the weavers on the ground will benefit as such initiatives help to create a wider and a more aware audience," Ms Patel says.

"The exhibitions can highlight, to a broader audience, the extremely skilled nature of the work that artisans do in India.

"They can help an audience or potential consumers appreciate the value of the handmade and better understand why handmade things cost more," she adds.

BBC Monitoring, external reports and analyses news from TV, radio, web and print media around the world. You can follow BBC Monitoring on Twitter , externaland Facebook, external.

- Published14 April 2015

- Published9 December 2013

- Published9 December 2013