Has India's contribution to WW2 been ignored?

- Published

More than two million Indian soldiers participated in World War Two

The numbers are staggering: up to three million Bengalis were killed by famine, more than half a million South Asian refugees fled Myanmar (formerly Burma), 2.3 million soldiers manned the Indian army and 89,000 of them died in military service.

South Asia was transformed dramatically during the war years as India became a vast garrison and supply-ground for the war against the Japanese in South-East Asia.

Yet, this part of the British Empire's history is only just emerging. By looking beyond the statistics to the stories of individual lives the Indian role in the war becomes truly meaningful.

Has the massive South Asian contribution to the World War Two been overlooked?

In some ways, it hasn't.

Everyone has heard of the Gurkhas and many people have heard something of the role of Indian soldiers at major battles like Tobruk, Monte Cassino, external, Kohima and Imphal.

The Fourteenth Army, a multinational force of British, Indian and African units turned the tide in Asia by recapturing Burma for the Allies. Thirty Indians won Victoria Crosses in the 1940s.

Untold stories

Increasingly, for both the World War One and Two, the contribution of soldiers from across the Empire-Commonwealth has been coming to light.

But what about all the other people who were caught up in the war?

Numerous other South Asian people sweated behind the scenes to secure supply lines and to support the Allies.

There were non-combatants like cooks, tailors, mechanics and washermen, such as a boot-maker to the Indian army named simply as Ghafur who died at the battle of Keren in present-day Eritrea and whose grave can still be seen there today.

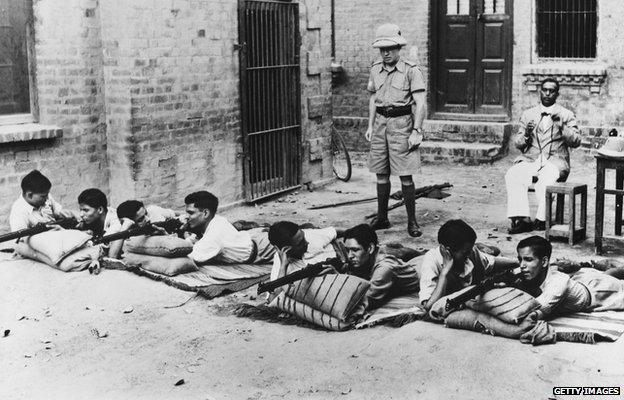

Soldiers from Punjab fought in the war

What do we know about the thousands of women who mined coal for wartime in Bihar and central India, working right up until childbirth? Or the gangs of plantation labourers from southern India who travelled up into the mountains of the northeast to hack out roads towards Myanmar and China? Or the lascars (merchant seamen) such as Mubarak Ali, remembered simply as "a baker" who died in the Atlantic when the SS City of Benares was torpedoed?

There were millions of other South Asians working towards the imperial war effort and we never hear about them.

It wasn't glamorous work: "coolies" loading and unloading cargo at imperial ports or clearing land for aerodromes did not share the prestige of fighter-pilots.

But their work could be very dangerous.

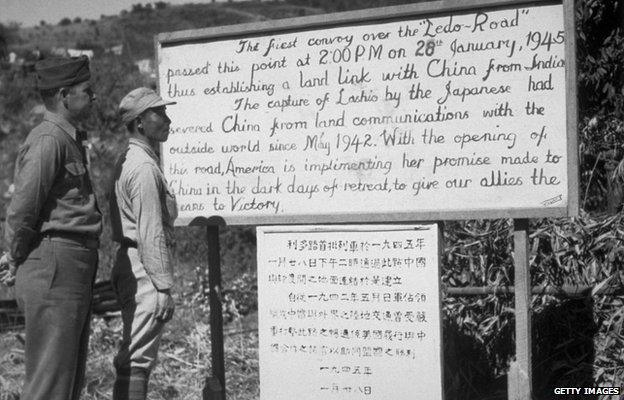

Thousands of Asian labourers died building treacherous roads at high altitude, including the Ledo Road between China and India, working with basic pickaxes and falling prey to malaria and other tropical diseases.

Harbour accident

Others died in industrial accidents - there was an incredible explosion in Bombay harbour in 1944, when a ship loaded with explosives and cotton caught alight, blew warships to smithereens and made over 80,000 homeless.

Factory workers and dockworkers also suffered from aerial bombardment - official figures suggest several thousand deaths from Japanese bombs on India's eastern coastline.

The men and women who kept the imperial war effort going in South Asia did not write diaries and memoirs.

An Indian air force pilot from Punjab in England

Often for them it was just a job, a way of earning enough money to eat.

They did not see it as belonging to a heroic part of world history, worthy of inclusion in history books. The illiterate left little trace of their service. And often their work - hard and poorly paid - was tough and dangerous whether it was wartime or not.

British officers wrote hundreds of accounts of their time in South Asia but there is not a single written memoir by an Indian rock-breaker, road builder or miner.

Quick profits

It's not a simple story of heroism or patriotism; many of these workers were more motivated by the need for bread than by the need to defeat the Axis.

And it's not a straightforward case of imperial exploitation - many elite South Asians made quick profits in the war and transformed their own fortunes.

Experiences of the 1940s depended on caste, class, vantage point and region: a Punjabi soldier could see things very differently to a metropolitan student in Mumbai (formerly Bombay) or a factory-owner in Kolkata (Calcutta).

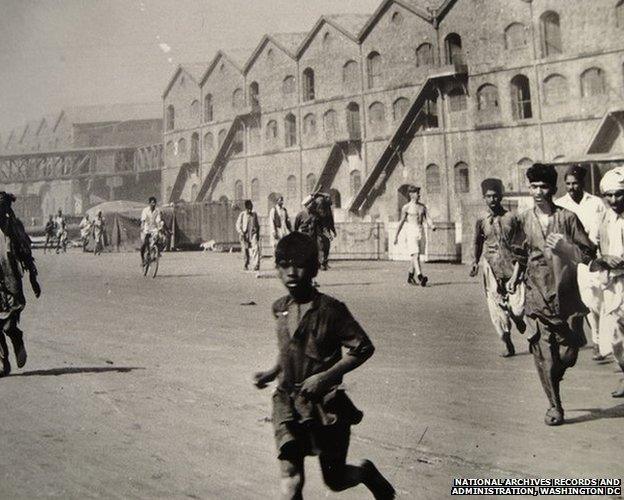

Locals flee from the Bombay docks in 1944 after an accident

Asian labourers died building the Ledo Road between China and India

Often those who worked towards the war were Anglo-Indians, adivasis [tribespeople], Parsis and Christians - and their histories slipped by the wayside during the writing of post-independence nationalist myths.

The people who made up the war effort soon had their lives shaped again by the Partition of 1947 and the carving up of new countries.

This wartime history belongs to Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan as much as to India.

In the rush to write new histories of nation states after 1947, much of the history of the 1940s was locked out from official memory. Tales of the freedom struggle took precedence. And in Britain and the US, the emphasis was placed on remembering military contributions to major battles, not on the everyday lives of anonymous workers.

As one report put it at the time, this was not the "forgotten army", but the "unknown army". Perhaps now we can finally start to appreciate the fullest extent of WW2.

Yasmin Khan is an associate Professor of History at the University of Oxford. Her book, The Raj at War: A People's History of India's Second World War will be published in July by Random House.