Does India's national anthem extol the British?

- Published

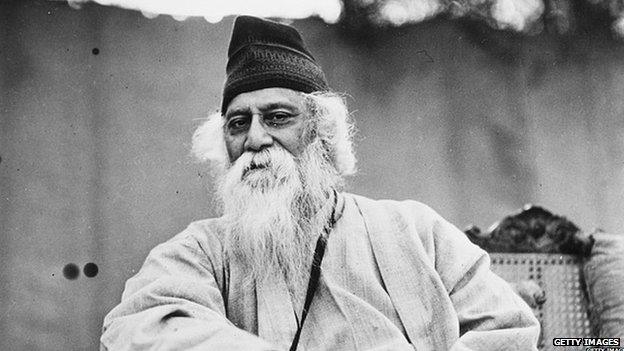

Tagore was the first Asian to win the Nobel Prize for literature

More than a century after it was first sung in the eastern city of Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), the song that later became India's national anthem is again mired in a worn-out controversy.

On Tuesday, the governor of Rajasthan state Kalyan Singh, a veteran BJP leader, pulled an old chestnut out of the fire by saying that Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore's Jana Gana Mana, had actually praised the British rulers. He said the phrase adhinayak jai he, which literally translates as "hail the leader" should be removed and replaced with mangaldayak, which means the "welfare giver" . His audacious remarks, external even made it to the front page of a prominent newspaper.

He is not alone. Former Supreme Court judge Markandey Katju wrote recently that Jana Gana Mana, which became India's national anthem in 1950, was "composed and sung as an act of sycophancy" to George V, the only British king-emperor to travel to India.

Mr Katju even offered some dubious evidence to support his thesis: the song was "composed at precisely the time of the visit" of the British king in December 1911, it does not "indicate any love for the motherland", the "lord or ruler" and the "dispenser of India's destiny" (another phrase in the song) in 1911 were the British rulers, and it was sung for the first time at a conference in Kolkata of the Congress party, which was held to welcome the king.

The song, written in Sanskritised Bengali, has had its fair share of controversies: some say it is deferential to the British monarchy; others say it fails to fully reflect India's races and regions.

But historians believe the claim about the song being a glowing testimonial to the British rulers by Tagore - the first Asian to win the Nobel Prize for literature and a patriot, who resigned his knighthood in protest against one of the bloodiest massacres in British history - is disingenuous.

Historian Sabyasachi Bhattacharya, who has written a definitive book on Tagore, believes that this "myth about the song" needs to be "refuted and laid to rest".

Tagore wrote the song on 11 December 1911. Next, day the Delhi durbar - or mass assembly when George V was proclaimed Emperor of India - was held.

The song was first sung on 28 December 1911 at the Congress session in Kolkata. It was also sung, as Mr Bhattacharya reminds us, at the foundation day programme of the Adi Brahma Samaj, a reformist and renaissance movement of Hindu religion, in February 1912, and included in their collection of psalms.

"Many years later fertile and malicious imagination connected the composition of the song and the durbar and it was rumoured that Tagore's poem was meant to be sung in the Delhi durbar," writes Mr Bhattacharya.

The truth was finally nailed by a letter Tagore wrote to his editor Pulin Behari Sen in November 1937. The poet said it was obvious that "neither the Fifth nor the Sixth nor any George could be the maker of human destiny through the ages".

"I had hailed in the song Jana Gana Mana that Dispenser of India's destiny who guides, through all rise and fall, the wayfarers, He who shows the people the way..."

Mr Bhattacharya says to see George V as the "object of worship in place of 'Dispenser of India's destiny..Thou King of all Kings' was only absurd, but also sacrilegious to Tagore".

Clearly, Tagore did not write the poem either for the British king or the Congress. "It was a hymn to his Maker, the guardian of the country's destiny," says Mr Bhattacharya. Something which many appear to be wilfully ignore - or forget.