Viewpoint: Why Britain does not owe reparations to India

- Published

- comments

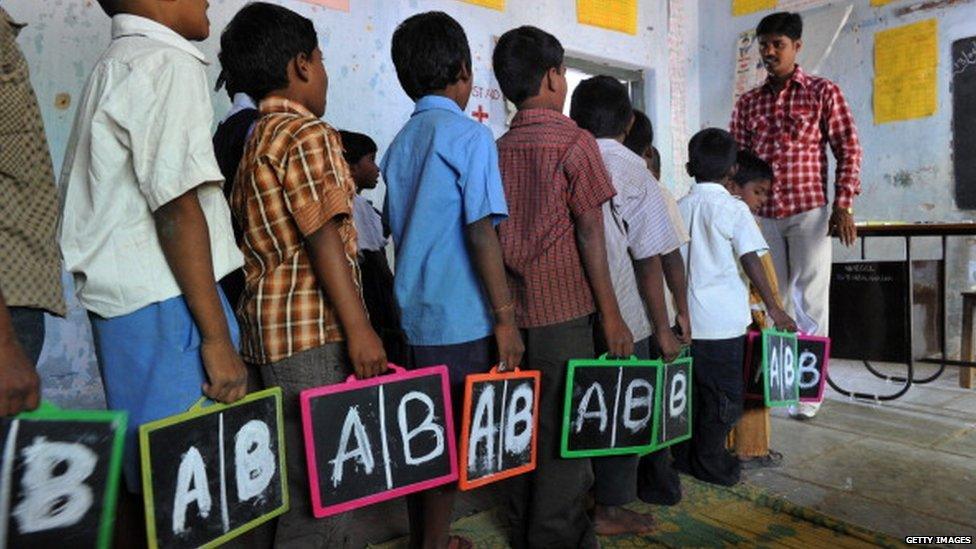

'The British did offer English as a unifying language'

At the end of May, the Oxford Union held a debate on the motion "This house believes Britain owes reparations to her former colonies". Speakers included Indian politician and writer Shashi Tharoor and British historian John MacKenzie. Mr Tharoor's argument in support of the motion has found favour among many Indians, where the subject of colonial exploitation remains a sore topic. Here, Professor MacKenzie, who spoke against the motion, offers his views.

Mr Shashi Tharoor is a remarkable man, a great ornament in India's diplomatic, political and literary life. He spoke at the Oxford Union reparations debate with great elegance and wit, but he overstated the case.

And he is wrong about reparations.

Having just emerged from editing a four-volume encyclopaedia of all empires in human history, I can say categorically that no empires have pursued tender or altruistic policies.

Empires happen because of imbalances in environmental opportunities, military and technological power, or capacities for state centralisation.

Or sometimes all three and more of those. And they always, without fail, pursue policies that benefit the rulers.

It would be quite wrong to create a myth of a peaceful "Merrie India" in the pre-British period.

Enriching the elite

India has been subjected to imperial formations for much of its history. In each case, people have been dominated for the benefit of the rulers.

This was certainly true of the Mughal Empire which preceded the British.

Countless people died in famines during the Mughal period, not least during the period when the Taj Mahal in Agra was being built.

Much of Indian wealth was creamed off for the benefit of rulers.

If it is true that it did not necessarily leave India, it is also true that it enriched a tiny elite, which certainly used military power and massacre and bloodshed to maintain their power. The militarisation of the Indian landscape with forts is evidence of this.

Over millennia of history, the locus of power and wealth has shifted back and forth.

When Europeans began their expansionist urges in the 1500s and 1600s, there can be no doubt at all that the great Asiatic Empires - the Ottoman, the Mughal and the Chinese - were much more powerful. It was only in the 18th Century that Europeans began to secure dominance. Now in the post-European age, the locus of power is moving back again.

A group of British expatriates, some in military uniform, sitting outside their house in India in 1880

European power was confirmed by wholly new forms of mechanised industrialisation.

When Mr Tharoor uses the word and suggests that Indian "industries" were destroyed, he is writing about two completely different things.

Indian "industries", while highly skilled in producing fine textiles, were essentially about craft production with relatively low levels of scale and technology.

European industrial production was unassailable worldwide because of the cheapness of the product. Craft production like handloom weaving was destroyed everywhere, including in Britain itself.

Weavers' thumbs

I am not sure of Mr Tharoor's source for the cutting off of weavers' thumbs.

It is not something I have heard of. What can certainly be said is that this was never official policy. If it happened at all, it must have been a localised, unofficial and illegal activity.

And if this practice had been publicised, it would have produced a storm of protest in Britain. Later in the 19th Century the British came to admire Indian crafts and argued that their values should be imported to the United Kingdom.

As with so much of the argument, the question of railways is largely correct, but some economic historians have suggested that Indian railways would have cost a great deal more if indigenous developers had had to seek capitalisation on world markets and buy in technology in a wholly unprotected way.

The fact is that India has one of the greatest railway networks in the world, a network which helped to bind the country together and, ironically, permit Congress nationalists to move around developing opposition to the British.

Britain also developed Western-style universities, a Western-style press, and a large publishing sector.

This placed the written word in the hands of much wider sectors of the population and, in all cases, served to promote political opposition to the British. It must remain doubtful that traditional Indian elites would have done this. Mr Tharoor is a great product of this shift to bourgeois learning.

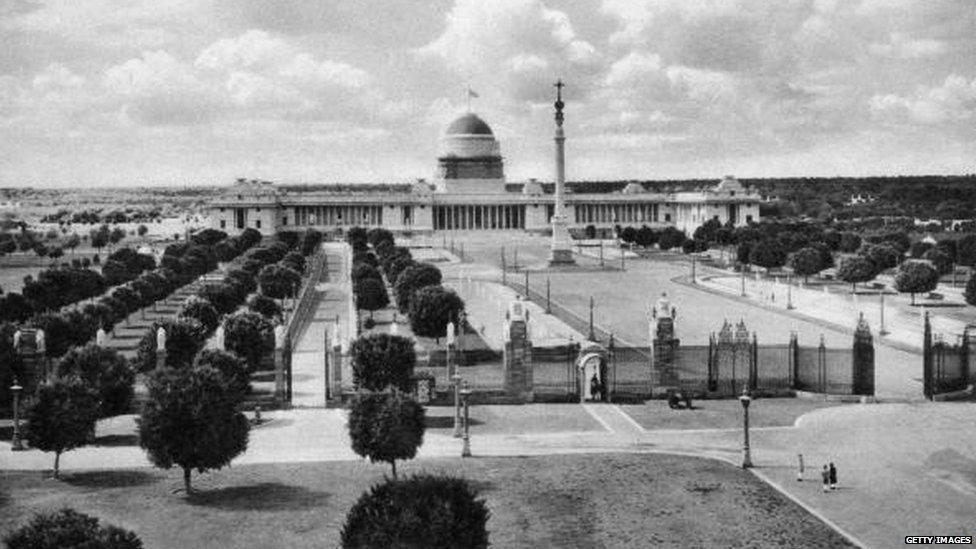

The British spent millions on the new capital at New Delhi

We should also remember that in some areas, Indian industrialisation actually destroyed the British equivalents.

An excellent example lies in jute manufacture.

Raw jute was exported to Scotland for manufacture in the city of Dundee. Already by the end of the 19th Century, Dundee's skilled workers and managers, imagining that there was room for all production, and pursuing their own personal interests, took the technology to Calcutta and the surrounding areas.

By World War One, Indian production was already much cheaper than British and the jute factories of Dundee went into steep decline, producing considerable misery for its population.

The British government did nothing to prevent this and Indian industry triumphed over British. To a certain extent it happened in other sectors too.

There can be little doubt that the British, by ultimately forcing the princely states into the independent state of India, helped to unify India while at the same time partitioning it and, it might be argued, protecting it from the tensions and problems that a much larger Muslim population might have produced.

Unifying language

The British did offer English as a unifying language, which certainly helped the survival of Indian democracy.

In the last years of their rule the British spent millions on the new capital at New Delhi, an imperial folly which left India with one of the greatest capitals in the world.

Today India has a major globalising middle class with tastes and pursuits (tourism for example) to match.

Bangalore has seen a tremendous amount of "outsourcing" of such functions as "call centres" which, together with its remarkable response to the opportunities of the latest digital technologies, has ensured that the balance has shifted in India's favour. British companies fostering this have indulged in a form of reparations.

Only one major country in the world responded to Western industrialism and modernism without the imposition of imperial control or its equivalent and that was Japan, a country quite unlike India in its geographical formation, the relative uniformity of its peoples, and its common culture and religion.

'By World War One, Indian jute production was already much cheaper than British'

Even Japan had the stimulus of the treaty ports which introduced Western-style trade, ship-building and technologies.

It can indeed be said that India's share of world GDP declined dramatically between, say, 1800 and 1947, but it must be remembered that economic revolutions, massive shifts in world population, and the dramatic expansion of other economies were all taking place throughout Europe, in the United States, in Latin America, Australasia, and the Far East during this period.

This great collapse in share was only partly due to British rule, but has to be seen largely in terms of great global shifts and stunning economic growth.

Finally reparations.

It was my argument in the Oxford Union debate that reparations were not the right answer, that they were essentially an impractical solution.

Ill omens

Precedents, such as [former Italian prime minister Silvio] Berlusconi's agreement with [former Libyan leader Muammar] Gaddafi, are ill omens. The calculation of reparations, their payment, ensuring that they went in the direction of the poorer in society, and their contribution to economic growth for all, would all be fraught with difficulties.

Atonement? Historians have been offering atonement through their writings for years and many superb Indian historians have taken up and sometimes modified these themes. Academic historians have considerable influence on the education of European, American and other elites.

All are fully aware of the iniquities and damage of imperialism (perhaps slavery is the worst example). We all seek atonement while recognising that the past is past and that we must guard against some of the modern equivalents of imperial exploitation that are still amongst us. Economic growth and improvements in health and social life must come from aid, support, fair and free trade.

The Koh-i-Noor diamond is a strange example for Mr Tharoor to use. It is surely absolutely symbolic of some unproductive aspects of Hinduism, as well as the power of earlier elites who had oppressed India just as much as the British.

John MacKenzie is emeritus professor of imperial history at Lancaster University and a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- Published22 July 2015