Why India needs a new debate on caste quotas

- Published

Some 300,000 members of the Patel community attended the meeting in Ahmedabad on Tuesday

Caste-related violence involving an influential community in India's Gujarat state left eight people dead earlier this week. The Patel community is demanding quotas in educational institutions and government jobs. Politician and writer Shashi Tharoor explains why India needs a new debate on affirmative action.

India has been shaken, and its thriving state of Gujarat paralysed, by a massive agitation by its influential Patel community.

Millions gathered in the state's major towns under the surprisingly belligerent leadership of a hitherto unknown 22-year-old called Hardik Patel, clamouring for their caste to be granted affirmative-action benefits known as "reservations".

Violence erupted, property was damaged, eight lives were lost and the army was called in. Hardik Patel was briefly arrested and, when his arrest sparked fury and more violence, released.

The agitation damaged not only property and people but also some of the fundamental assumptions of Indian politics.

Discrimination

India's constitution, adopted in 1950, inaugurated the world's oldest and farthest-reaching affirmative action programme, guaranteeing scheduled castes and tribes - the most disadvantaged groups in Hinduism's hierarchy - not only equality of opportunity but guaranteed outcomes, with reserved places in educational institutions, government jobs and even seats in parliament and the state assemblies.

These "reservations" or quotas were granted to groups on the basis of their (presumably immutable) caste identities. The logic of reservations in India was simple: they were justified as a means of making up for millennia of discrimination based on birth.

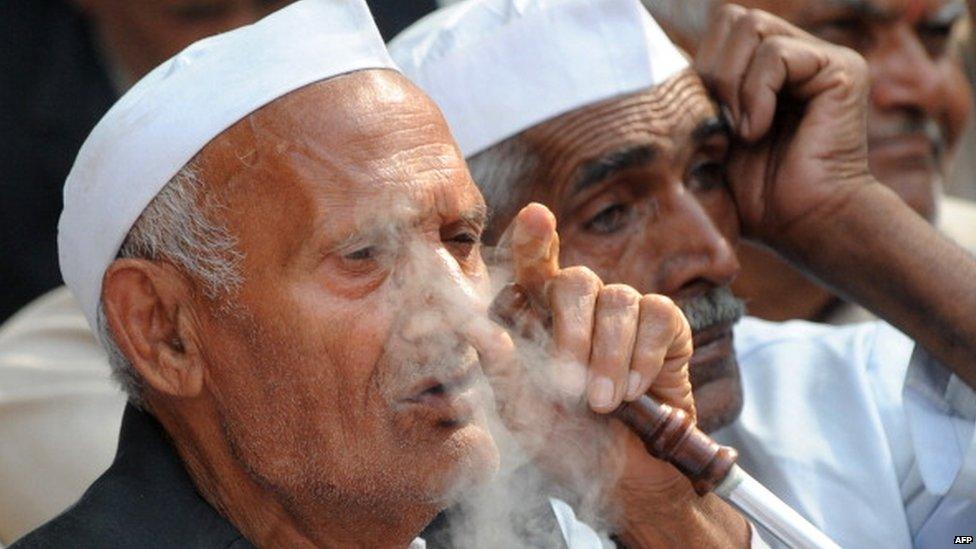

Eight people, including a policeman and a father and son, were killed in the violence in Gujarat

It was a small way of compensating the millions of unfortunates who suffered daily the inequities and humiliations of untouchability.

Reservations became more political in 1989, when the VP Singh, external-led government of the day decided to extend their benefits to Other Backward Classes (OBCs), based on the recommendations of the Mandal Commission, external.

The OBCs hailed from the lower and intermediate castes who were deemed backward because they lacked "upper caste" status.

Prominent and successful

As more and more people sought fewer available government and university positions, we witnessed the unedifying (and unwittingly hilarious) spectacle of castes fighting with each other to be declared backward: the competitive zeal of the Meena and the Gujjar communities in Rajasthan, castes not originally listed as OBCs, to be deemed more backward than each other would be funny if both sides weren't so deadly serious.

As an uncle of mine sagely observed, "In our country now, you can't go forward unless you're a backward."

The Patels, however, are an unlikely caste to be seeking such recognition: they are in fact dominant in Gujarat, prominent, successful and wealthy beyond their share of 15% of the state's population.

Gujarat Chief Minister Anandiben Patel is from the community; several Patels occupy important portfolios in her cabinet. Hardik Patel says the majority of his fellow Patels are less well off.

India's Gujjar community is also demanding reservation

India's top court has struck down a directive which included the powerful Jat caste in the list of OBCs

But to suggest that the caste as a whole deserves reservations strikes most people of Gujarat as absurd.

The problem, as all too often in India, is politics.

India's first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru had hoped that caste consciousness would wither away after Independence, but the opposite has happened.

Because caste was such a powerful source of self-identification, it proved to be a useful tool of political mobilisation in India's electoral democracy: when an Indian casts his vote, he too often votes his caste. Granting sops to various castes proved a major vote-catcher for India's politicians.

The number benefiting from such sops varies from state to state, but has reached extreme proportions in a state like Tamil Nadu, where 69% of government jobs and educational positions are reserved for a range of deprived and disadvantaged castes - so much so that the state has a cottage industry of fake caste certificates for Brahmins seeking to pass themselves off as Dalits, formerly known as untouchables.

Backlash

Inevitably, a backlash has set in, with members of the forward castes decrying the unfairness of affirmative action in perpetuity, and asking whether it is reasonable, for instance, that the daughter of a senior government servant from a backward caste should benefit from reservations while the son of his upper-caste driver or clerk competes for limited unreserved seats.

Some argue for reservations to no longer be caste-based but tied only to economic criteria, with the poorest of all castes benefiting from them rather than the better-off of some castes. (Many suspect that Hardik Patel and his fellow Patels aren't really looking for reservations: by demanding the impossible, they are actually seeking the abolition of the present system.)

The current beneficiary castes, however, respond hotly that such a change overlooks the social discrimination that comes with, for example, the stigma of untouchability: however prosperous a Dalit family, many upper-caste Indians would not grant it respect unless its members enjoyed the status that comes with, for instance, a government position.

The quotas were justified as a means of making up for millennia of discrimination based on birth

Gujarat's Patel agitation has succeeded in starting a nationwide debate on reservations.

It has an interesting partner in India's Supreme Court, which earlier this year struck down the government's notification including the powerful Jat caste in the list of OBCs. , external

The judges' rationale was that the state should not go by the "perception of the self-proclaimed socially backward class or advanced classes" on whether they deserved to be categorised among the "less fortunates".

Most significantly, the court held that caste, while acknowledged to be a prominent cause of injustice in the country historically, could not be the sole determinant of the backwardness of a class.

While caste may be a prominent factor for "easy determination of backwardness", the top court discouraged "the identification of a group as backward solely on the basis of caste" and called for "new practices, methods and yardsticks" to be evolved.

"The gates would be opened only to permit entry of the most distressed. Any other inclusions would be a serious abdication of the constitutional duty of the State," the court warned.

This suggests that the Patel's demands to be classified as OBCs will not stand the scrutiny of the Supreme Court. But it also suggests that India's entire range of affirmative action practices will need to be reviewed.

The battle has truly been joined.

- Published22 June 2013

- Published10 March