Dealing with dengue: Lessons from the fever crippling Delhi

- Published

Hospitals and clinics across Delhi have been inundated with patients as Justin Rowlatt reports

An auto rickshaw buzzes to a halt outside the Bara Hindu Rao Hospital in Delhi, one of the biggest in the Indian capital.

Two women get out and pull a young man after them. His body is limp.

The women take an arm each and manhandle him into the casualty area where they join a crush of people.

Every day this hospital sees hundreds of people with the high fever and agonising joint pain that has earned dengue its alternate name: breakbone fever.

Security guards have been deployed to keep order but even so fights are still common. People are that desperate to see a doctor.

Tough decisions

Delhi is in the grip of its worst outbreak of dengue in years. According to the official figures, 25,000 people have been infected in India this year. The real figure is believed to be hundreds of times higher.

And the scale of the outbreak means hospitals have to make tough decisions.

One the day we visit, it is Dr Sonali Chaturvedi's job to decide who gets admitted. She says she turns nine out of 10 people away.

Most people recover after a week or two of severe illness, but a few will go on to develop the most serious and life-threatening form of the disease.

That's when the plasma starts to leak out of patients' blood vessels. It is known as dengue haemorrhagic fever.

Nine of ten patients are turned away in Delhi hospitals as doctors struggle to deal with the deluge of cases

The only way to tackle dengue is to get to the root cause.

Official figures say 25,000 people have been infected by dengue. The real number is believed to be much higher

The medical director of the hospital, Dr Hemant Sharma, leads me through wards full of dengue sufferers.

Ceiling fans churn the torpid air above the rows of beds. Space is so short some patients have to share a bed.

And, Dr Sharma says, that's after the hospital has cancelled all emergency surgery to free up more wards for dengue.

All government doctors have been told they can't take any leave until the disease subsides and that won't happen for weeks - until the first winter chills kill off the mosquitoes that carry the disease.

There is no vaccination to protect you from dengue, and no cure if you contract the disease, so the only way to tackle dengue is to get to the root cause.

Hunting for aedes

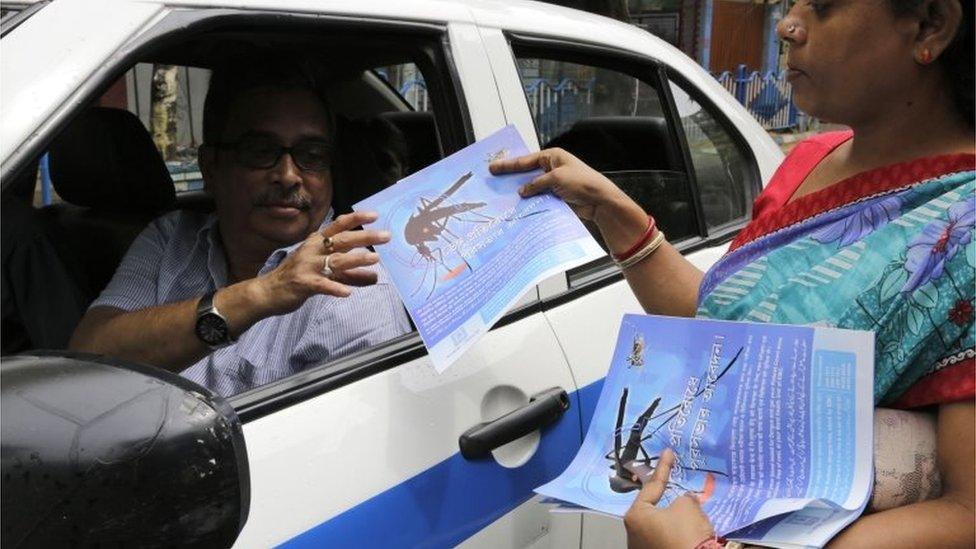

In a narrow alley in Delhi's old town I meet up with a team of 30 government employees, some of up to 10,000 who are sent out into the city each day to warn of the dangers of dengue and to try and hunt down the aedes mosquitoes that carry it.

The only way is to go house to house, checking for anything that could hold even a tiny puddle of water.

Babita Bisht, who is in charge of the small team, tells me aedes mosquitoes can breed in just a few millimetres of clear water.

Government employees are sent into the cities to warn of the dangers of dengue

She's a trained entomologist - an insect expert - and I'm surprised when she tells me she loves the aedes mosquito and loves to find it breeding.

After less than half an hour a shout goes up. One of the team has found a water vessel on the roof of one of the houses. Hundreds of aedes larvae squirm and wriggle inside.

The family that live here will face a fine designed, says Babita, to encourage people to take more care to get rid of anything the mosquitoes could breed in.

'Spread across the world'

Dengue is a disease of modernity. Fifty years ago just a couple of countries reported dengue outbreaks, now it is endemic in more than 120 nations.

The transport networks that knit our world together have spread the mosquitoes across the world and the explosion in urban living over the same period has ensured a ready supply of people to feed on and all sorts of new habitats to live in.

Over the last few decades the rate of infection has increased thirtyfold, says Neena Valecha, a world expert on dengue and the head of India's national mosquito research centre.

The mortality rate is fewer than one in a hundred but with the World Health Organisation estimates there at least 100 million infections a year so it is still a very serious health issue.

And she warns that dengue will continue to spread out across the world.

Climate change is likely to make the warm, wet conditions dengue mosquitoes love even more common.

Dengue fever

Dengue fever is prevalent in sub-tropical and tropical regions, including South East Asia and South America

It is a major cause of illness worldwide, causing about 100 million episodes of feverish illness a year

Symptoms include high fever, aching joints and vomiting

Complications can prove fatal in extreme cases

There are four major strains of the virus

- Published16 September 2015

- Published16 September 2015