Why caste is still key in Indian politics

- Published

Bihar recorded a 57% turnout of voters during the first phase of polls on Monday

You already know far more than you ever wanted to about Donald Trump's hair - not to mention his views on women and Mexicans - but how much do you know about politics in the world's fastest growing large economy?

Mr Trump will almost certainly never face the electorate, and even if he does it won't be for a full year. Mr Modi, on the other hand faces a crucial electoral test right now.

The second phase of elections is being held today in India's most intriguing and - until fairly recently - its most lawless and disreputable state.

Indian elections are mind-bogglingly complex. Economic class, ethnicity, regional identity, religion - sometimes even politics - all play a role.

But the key factor is still caste.

Blocked reforms

Indeed, Mr Modi's genius - or good fortune, depending on where you stand - has been that he has managed to lift himself and the party he leads above the narrow appeal of caste.

Traditionally his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has drawn support from upper caste Hindus - not a big enough base for a national party.

Mr Modi won a landslide a year and a half ago by hugely widening the party's appeal, persuading hundreds of millions of Indians that only he could knock the economy into shape and deliver growth and prosperity to the nation.

Elections are being held for 32 seats on Friday

Mr Modi is slated to appear so many rallies he's been accused of "carpet bombing" Bihar

The problem is his reform agenda has been blocked in the upper house of parliament. He needs to win every state election from now to the next general election to get anywhere near the majority he needs.

That's why he's investing so much in the election in Bihar, India's poorest and third most populous state.

He is slated to appear at so many rallies he's been accused of "carpet bombing" the state and because the party hasn't named a candidate for chief minister - the top job in the state - he's the only figurehead.

Tight contest

That brings its own risks, massively raising the stakes for Mr Modi. A loss will be a huge blow to his reputation and will embolden opposition parties across India.

The polls say the ballot is too close to call and Mr Modi is up against two of the most seasoned - and successful - players of caste politics in all India.

These are regional leaders who have learnt to exploit the key advantage lower-caste voters have: their sheer weight of numbers. About half the Indian population is classified as lower caste.

These caste-based politicians have learnt that by ruthlessly targeting their message at the narrow slice of the population they represent they can win state elections.

The BJP and its national rival the Congress party, meanwhile, has to water its message down to attempt to appeal to almost everyone.

Laloo Prasad Yadav, or Laloo as he is universally known in India was one of the first post-independence politicians to refine this strategy down to a fine art.

He ruled Bihar for 15 years thanks to the seemingly impregnable electoral alliance he forged between the state's Muslims and the large, traditionally cow-herding, Yadav caste that delivered 30% of the vote at every election.

Laloo Yadav himself has been convicted of corruption

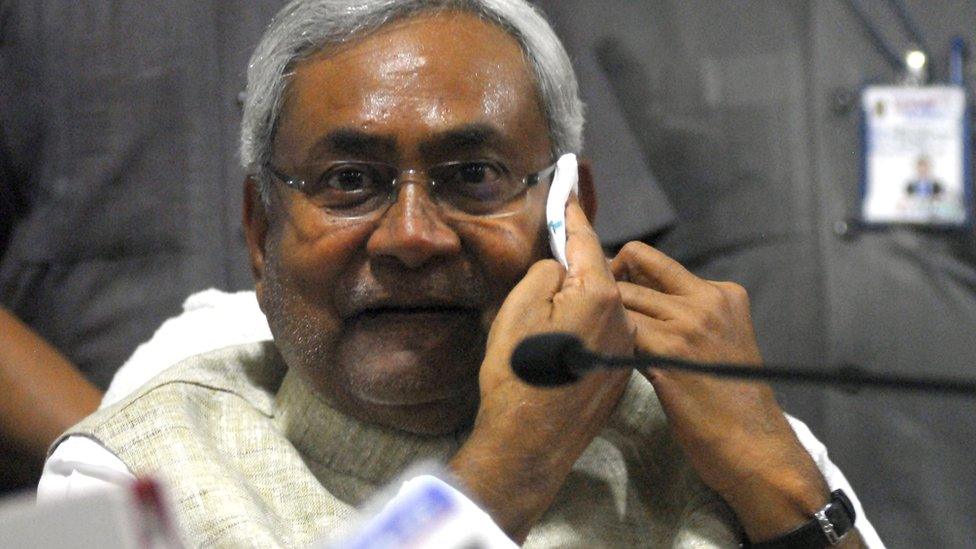

Until very recently, Nitish Kumar was a strong supporter of the BJP

But the appeal to caste identity tends to be linked to appeasement in India: politics becomes almost exclusively about what you can deliver - jobs, housing, subsidies - for your fellow caste members.

That is what critics say happened in Bihar under Laloo. Law and order wasn't a priority and kidnapping flourished alongside the state's traditional mango and lychee industries.

And gradually the chaos and economic decline of Bihar began to weaken the electoral alliance he had created.

Socialist champion

Laloo's nemesis was another expert orchestrator of caste allegiance, Nitish Kumar. He built his support in Bihar by cleverly picking off disaffected lower caste voters and Muslim voters from Lalu's vote bank.

Like Laloo he styles himself a socialist, but unlike him, also a champion of law and order who would put development first.

And Bihar did begin to improve under Kumar. He got rid of the caste-cronyism that marred Laloo's rule and has made the state more law abiding and more prosperous.

And, until very recently, Mr Kumar was a strong supporter of the BJP. But he didn't think Mr Modi was fit to be prime minister and cut his ties with the party.

Bihar is one of India's poorest states

Instead Mr Kumar formed a "Grand Alliance" with his sworn enemy, Laloo. The idea is that together they can unite lower caste voters against Mr Modi.

And on balance they probably have the edge over the BJP.

Which is where the issue of beef comes in.

Mr Modi has been widely criticised for waiting so long to speak out against the lynching of a Muslim man by a mob of his Hindu neighbours for allegedly slaughtering a cow, a sacred animal to Hindus.

Cynics here say the issue was exactly what he needed to drive a wedge between the lower caste Hindus and the Muslims that are the electoral bedrock of the Grand Alliance.

But don't hold your breath to find out who prevails. This being India even state elections are democratic contests on a truly staggering scale.

There are 66 million people eligible to vote - Britain boasts an electorate of just 45 million. The ballot will be conducted in five phases and take more than three weeks to complete.

The results are expected on 8 November.

- Published9 September 2015