Why the UK visit is designed to dazzle Modi

- Published

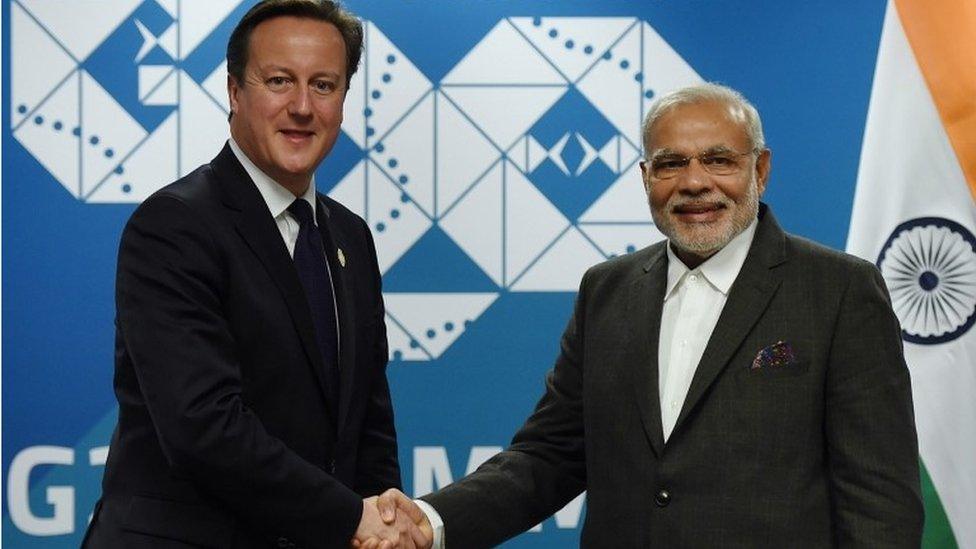

Mr Modi's visit is about establishing a deeper connection between the two prime ministers

For David Cameron, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's visit to the UK is personal.

Leading British officials involved with the visit underline that Mr Modi's three days in the UK - 12-14 November - is all about convincing the Indian leader that Britain is a friend like none other.

Equally, it is about establishing a deeper connection between the two prime ministers, one that they do not share at present.

Apart from the many memorandums that will be signed and business deals worth $15bn (£9.9bn) agreed, the idea is to provide Mr Cameron and Mr Modi space to relate better with each other.

Mr Cameron will have adequate opportunity to do this at Chequers, his country residence, where Mr Modi will stay overnight.

As importantly, the visit is about tickling the Indian prime minister's vanity, something that insiders in the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) appear to understand all too well.

Mammoth event

The weather permitting, Mr Modi's drive down Horse Guards en route to his first official meeting with Mr Cameron on Thursday will be accompanied by a fly past by the Red Arrows, the Royal Air Forces' pioneer aerobatic team.

The London Eye will be lit-up in the colours of the Indian tricolour. Mr Modi will even be given a guard of honour, a privilege ordinarily reserved only for heads of state. Mr Modi is a guest of state, given that India's President, Pranab Mukherjee is the head of state.

But most importantly, a mammoth event organised at Wembley Stadium on Friday is designed to impress the Indian prime minister and most of India, who will watch him speak from the centre of the football pitch.

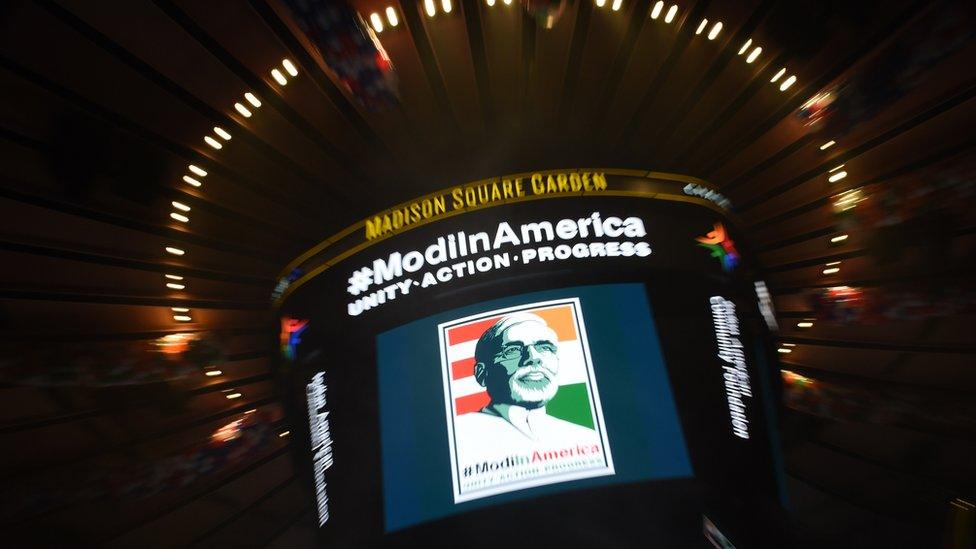

Wembley promises to make last year's much-reported celebration at Madison Square Garden in New York, where Mr Modi addressed mostly Indians in the US, look microscopic in comparison.

An estimated 70,000 people, mostly of Indian origin will be present, as also the entire British cabinet. It promises to make last year's much-reported celebration at Madison Square Garden in New York, where Mr Modi addressed mostly Indians in the US, look microscopic in comparison.

Unusually, and perhaps for the first time in Mr Cameron's political career, he is expected to introduce Mr Modi and then walk-off the stadium.

The optics will say it all. Mr Modi might be in the UK, but this is his show for his people.

The timing of the event is no mistake either. It's on the same weekend as when the majority of the 1.5 million-strong Indian diaspora in the UK will celebrate Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights.

It provides Mr Cameron with the opportunity to tap into an electorate that has become increasingly important in winning marginal seats in UK elections.

Dadabhai Naoroji, a founder of the Indian National Congress, became the first India-origin MP in the House of Commons (representing the Liberal Party) in 1892. There are currently 10 MPs from the Indian diaspora in parliament.

Mr Cameron understands well that relations between India and the UK in the current milieu is all that more promising because of this diaspora.

His government seems to understand that the biggest take-away of this visit will have less to do with deals and mergers than opportune photographs curated to remind the Indian prime minister of all that Britain stands for.

Reform agenda

Not the least of these include an address in the British parliament and lunch with the Queen.

Yet, and the optics notwithstanding, Mr Cameron is under pressure from UK Inc to push the Indian prime minister on a reform agenda that they argue is yet to be realised.

Mr Modi's supporters here expect India to maintain an average growth rate of nearly 8% over the next decade. Equally, they suggest that China's will slow further down to an average of 5%.

This is all part of the promise narrative carefully crafted by the Modi government, but which investors in the UK appear to have only half-swallowed.

They are keen to explore the potential embedded in his promise-laden script, but are quick to realise that even if China's growth rates halve in the next decade, it will still be double in size of the Indian economy.

Further, Mr Modi came to power promising a "predictable, stable, and competitive" tax regime. This, they argue, has not yet happened. The prime minister also undertook to introduce what is called the Goods and Services Tax (GST), a uniform national value added tax in India. His government is unlikely to be able to do this by the date - April 2016 - set by them.

Mr Modi's supporters here expect India to maintain an average growth rate of nearly 8% over the next decade

Most importantly, financial houses have grown suspect of the Indian government's limited appetite for risk.

They complain of a continuing protectionist attitude held by the Modi government that despite its majority mandate, it is unwilling to shake.

While promise and sentiment provides enough to keep big business in the UK optimistic about investing in India, the window for such hopefulness has a sell-by-date.

Between the night at Chequers and the evening at Wembley, this is a message that Mr Cameron is expected to relay without qualification.

Embracing the optimism

In sum however, this visit is designed to dazzle the Indian prime minister, the Indian people, and allow Mr Cameron the opportunity to place Britain at the centre of Modi's political imagination.

India is one of the world's fastest growing economies

Heritage issues to do with Pakistan and Kashmir that have strained relations in the past, are unlikely to occupy any broadsheet space. Even India's position on climate change, that No 10 reportedly views as obstructionist, will be placed in the freezer for the time being.

The idea is simple: to unequivocally embrace the optimism set out by Mr Modi. Reservations with regards to India's advance in her immediate neighbourhood and in international negotiations will be parked away for the time being.

Dr Rudra Chaudhuri is a senior lecturer in South Asian Security and Strategic Studies at King's College, London