What Indians have done to world cuisine

- Published

If the Chinese knew about 'Manchurian' and 'Schezwan' they might instantly request a divorce

About 75km (47 miles) northeast of Mumbai, along India's first access-controlled expressway, there is a slightly grubby food court that offers a Mexican dosa, a Russian-salad dosa and a Schezwan dosa.

Packed with families from a middle class that has, roughly after the turn of the century, fallen in love with the automobile and the open road, the expressway food plaza hints at the restless energy of emerging India - a constant search for new destinations and experiences.

The dosa, a popular rice pancake, usually crispy brown on one side, white on the other, is itself a traveller.

This is the fourth article in a BBC series India on a plate, on the diversity and vibrancy of Indian food. Other stories in the series:

It originated in south India but with growing internal migration, is now known nationwide.

India's great restlessness has forced the birth of hundreds of dosa varieties, more than this article can record.

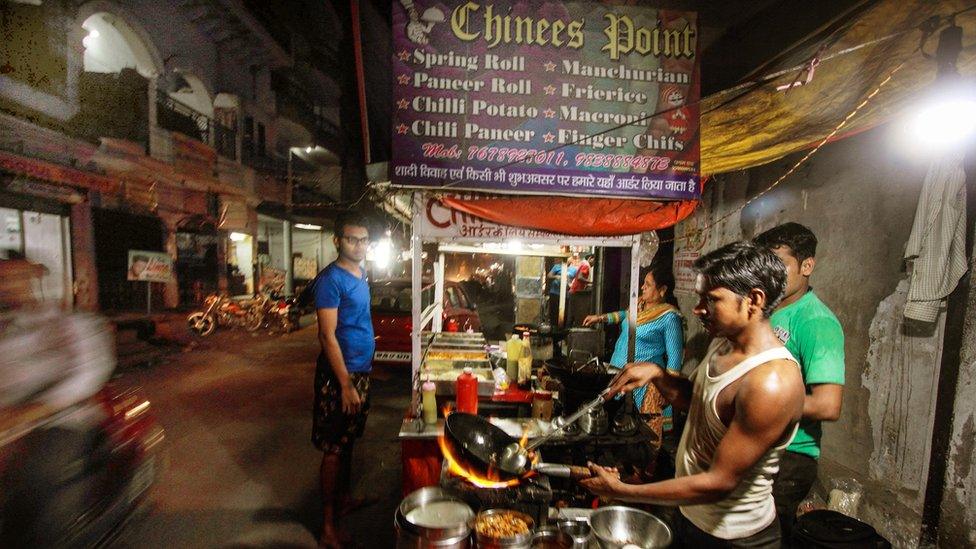

The Schezwan saga

Of these, few dosas signify the modern middle-class Indian's food choices and the national proclivity to marry culinary cultures - although the Chinese, if they knew, might instantly request a divorce - than the "Schezwan dosa".

Relations between the world's two most populous countries are scrappy at the best of times, and the most generous way to describe Indian-Chinese relations would be suspicious incomprehension.

Yet, the ubiquitous presence of the Schezwan dosa across India reveals an aspect of Chinese culture that Indians have enthusiastically adopted, albeit in a form no self-respecting Chinese would recognise, such as the word "Schezwan".

Indian-Chinese can take many forms depending on what part of the country you are in

The dosa, a popular rice pancake, usually crispy brown on one side, white on the other, is itself a traveller

"Schezwan" is a corruption of "Sichuan", a Chinese province that lends its name to a style of cooking known for the use of hot peppers - or chillies, as we call them.

Indians take enthusiastically to any cuisine that uses chillies, and in our restless search for new flavours - especially after a tide of growth, sparked by economic reforms in the 1990s - a home-grown, bright-orange "Schezwan (also spelt Shezuan)" sauce seeped rapidly into not just Indian street food but posh restaurants and home kitchens.

No one really knows how Schezwan sauce and the dosa met, but of that meeting there are myriad manifestations, such as the Schezwan butter dosa, the Schezwan masala dosa, and the Schezwan noodle dosa.

In the expanding universe of the Schezwan dosa, nothing is as bizarre - and popular - as the Schezwan chopsuey dosa.

It incorporates all the ingredients I mentioned and then some: a dosa stuffed with butter, spicy vegetables and noodles, tossed in a sweet-sharp Schezuan sauce.

"Take the typical potato stuffing out of the masala dosa and replace it with a tongue-tickling Schezuan chopsuey," writes food diva for the middle-class, Tarla Dalal, on her website, "and there you have a unique snack that is both filling and tasty. With noodles and colourful veggies, this dosa's stuffing is quite sumptuous (sic) too."

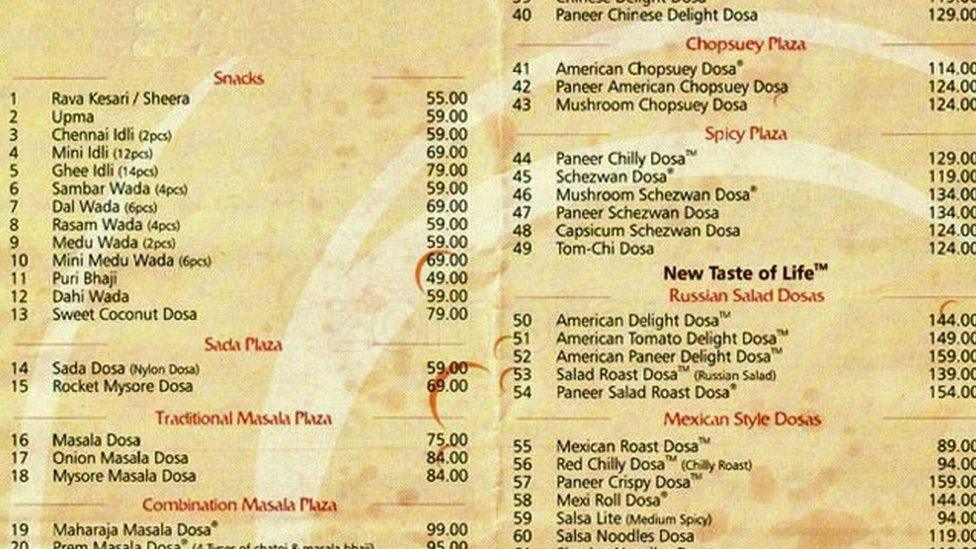

Items from an Indian-Chinese menu

Menus such as this one from Dosa Plaza are a common sight in India

Veg balls in black bean

Paneer (north Indian cottage cheese) crispy

Paneer stick in - what else - Schezwan sauce

Chow chu potatoes

Potato-jiang chilly

Sauces such as chilli, garlic, Schz. (you know what that is), black garlic, hot garlic and - my favourite - human. Human? Oh alright, that's probably a typo.

As you travel across India, you will also find (on the western, or Konkan, coast) Konkan-Chinese with a preponderance of coconut; Telugu-Chinese which is laced with super-spicy chillies from the southeast; and paneer (or cottage-cheese) heavy Sino-Ludhianvi.

Food writer Vir Sanghi says that no one from China would recognise any of these culinary digressions as Chinese, but he offers this justification: "No Indian would eat the so-called Balti rubbish that British call Indian food in the Midlands."

Spice imperative

Chinese cuisine - or, a vague idea of it - may top the food-fusion list of Indians, but as incomes, enthusiasm and the desire to experiment grow, no national culinary tradition that is strong on spice is safe.

In a country where those who suspect even a hint of blandness in food call for raw green chillies as compensation - hard as it might be to conceive today, Indians never knew of the chilly until the Portuguese ferried it over during the 16th Century - cuisines that use strong spices are favoured but not necessarily.

So, Indians are latching on to Thai, Mexican, Indonesian, Malay and Italian food, the last being a particularly good example of how cuisines that appear inherently alien are forcibly subsumed.

Multinational food chains know better than to ignore the spice imperative.

So McDonald's has a best-selling, spiced vegetarian Mac Aloo Tikki (potato patty) burger, Pizza Hut offers a "curry crust" flavoured with coriander, cardamom and fenugreek and Dominos has a "southern chilly chicken" topping.

The rich may enjoy those fancy tortillas and baos, but the middle classes are still content with the wonders of Schezwan

Newer, wilder interpretations of foreign fusions include spiced chicken tikkas wrapped in tortillas (with tandoori salad and garlic aioli), samosas - savoury puffs - stuffed with pizza, and Punjabi butter chicken gravy stuffed into a bao, a Chinese steamed bun.

The extent of experimentation appears to - anecdotally - correlate with disposable income.

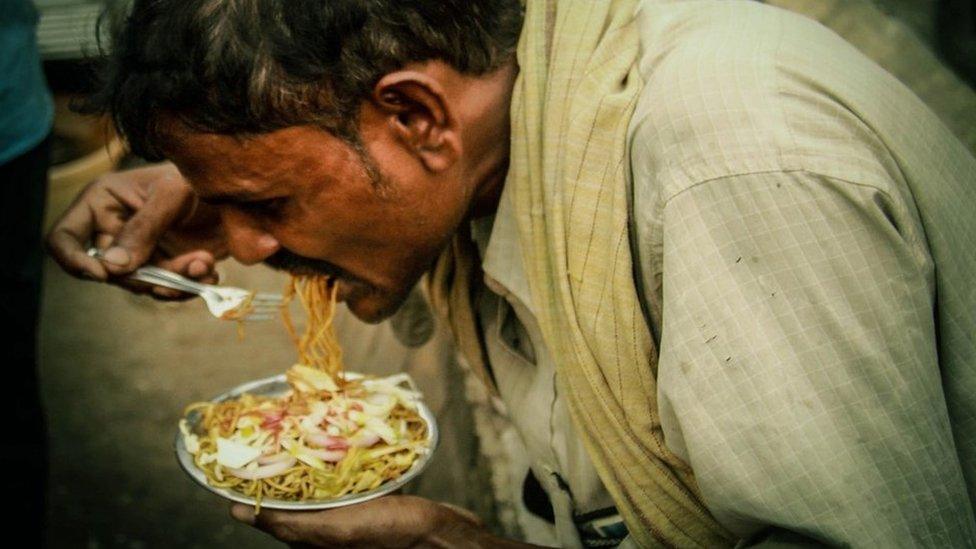

The rich may enjoy those fancy tortillas and baos, but the middle-classes are still content with the wonders of the Schezwan dosa.

The poor may appear to have few choices, but street carts with cheap "gobhi (cauliflower) manchurian" proliferate in the dustiest small towns.

When they do trade cycles for scooters, the first thing they will do is ride out for a Schezwan dosa.

Samar Halarnkar is the editor of Indiaspend.org, external and a food writer who runs the blog marriedmaninthekitchen.tumblr.com, external.