What stands in the way of India's digital dream?

- Published

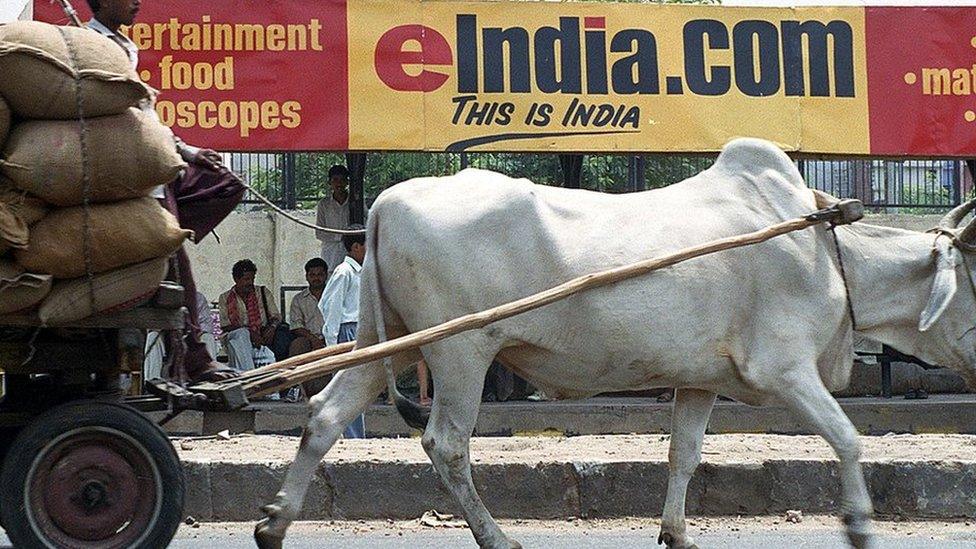

Traditional India is embracing mobile technology to boost growth

India appears to be on its way to be a connected, digital and mobile-first society. But dig a little deeper and you will uncover various hurdles, writes technology expert Mohit Rana.

Telecoms narrative in India over the past three years has been dominated by growth in mobile data with 3G and 4G services being rolled out and smartphones growing exponentially.

According to latest reports, India has over 300 million internet subscribers. Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government has set an ambitious target of getting 600 million broadband connections at speeds of over 2Mbps by 2020.

Policy makers seem to believe that cellular networks will play the same role for broadband data as they did for voice 10 years back - allow mass adoption and help achieve parity with developed countries.

But this is unlikely to happen as data usage and economics are very different. Cellular networks, with limited capacity and variable cost structures, are better suited to voice.

Cellular operators in India can meet the voice traffic demand for 900 million customers with only 6-10 MHz of spectrum per operator.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi hopes the step up to 4G will accelerate economic growth

But when it comes to data, the upper usage limits per subscriber are yet to be tested. Consumers in developed markets are hitting 10GB per month and growing rapidly.

Cellular networks globally are struggling to meet the data demand even with 50-70 MHz of spectrum. Leading Indian operators only have about 25MHz planned for data.

Distant dream

The pricing adds to the complexity. Cellular data is priced with the aim to sell limited capacity at higher rates. On the other hand, good quality fixed line networks provide almost unlimited capacity at low costs.

It is no different in India where fixed data plans are available for 20 rupees (30 cents; 20 pence) against cellular data at 200 rupees.

The price difference means that almost 90% of data globally is carried on fixed networks. This dichotomy works well for developed countries that have almost 75% of households covered by fixed broadband.

However, this dual broadband access option is a distant dream for India. Currently, India has less than 15 million fixed broadband connections (3% of households). That means only about 60 million consumers (about 20% of total internet users) are able to access fixed broadband at home.

These same high-income consumers account for most of the 3G/4G connections.

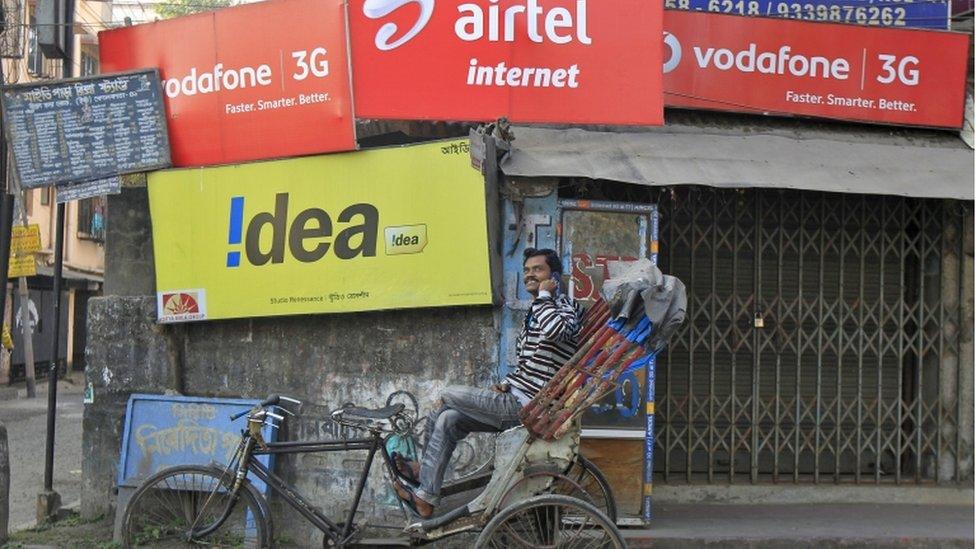

India's telecom market is a crowded place

It is the next 1.2 billion people with no access to a fixed broadband connection that are severely disadvantaged.

They have to rely only on cellular data which at 200 rupees is lower than global benchmarks on mobile data costs, but is still more than their current average monthly expenditure on mobile phone plans.

Hence, even after acquiring smartphones, social network accounts and local language typing skills, 80% of data subscribers consume less than 100MB per month, most of it on 2G.

The next lower level of income segment is still to join the party and will be able to afford even less.

Digital gap

One could argue that with the launch of 4G networks by large players and availability of more spectrum, things will change. But the reality is that while prices may drop slightly, it is unlikely to be enough to fundamentally change the affordability.

Operators have limited ability and incentive to drop prices since even at current rates, data traffic is growing at 100% and networks are stressed.

Moreover, any reduction in price will lead to increased traffic, further clogging networks and impacting user experience across voice and data.

And the increase in revenues will be marginal at best.

Flat or declining voice revenues over last several quarters have already limited operators' capacity to invest in more network and spectrum.

Leading Indian operators only have about 25MHz planned for data

The implications are immense - the widening digital gap will mean inequality of information and access to opportunities.

This will impact the government's plans to leverage internet and broadband as a means of inclusive growth by driving access to education, health, banking and information.

Various internet ventures also rest on a huge population base freely using broadband.

If most consumers have only a limited amount of data to consume, they will aggressively prioritise their usage and most smartphone applications will not even make it to the trial stage. Business models will hit a wall after 60 to 100 million users.

Once 600 million citizens armed with smartphones - and votes - start complaining about expensive data, it could evolve in several interesting directions, particularly in a democracy used to freebies and subsidies.

The government is hoping for some more private sector magic, but this is one area where just auctioning more spectrum will not be enough - much more direct and urgent action is needed to provide cheaper broadband access to the masses.

Mohit Rana is a partner in global management consulting firm AT Kearney's Gurgaon office