How will Delhi's 'odd-even' car rationing work?

- Published

In an attempt to curb alarming levels of pollution in the Indian capital, Delhi, authorities have announced that private cars with even and odd number plates will be allowed only on alternate days from Friday.

The "odd-even" car rationing experiment will run for an initial two-week trial period after which the government will decide whether to extend it or junk it.

The city - the most polluted in the world, according to the World Health Organisation - has been experiencing hazardous levels of pollution this winter - and the government believes that draconian measures are needed to help improve the air quality.

The BBC's Geeta Pandey in Delhi explains how this formula will work.

How will the 'odd-even' plan work?

For the first 15 days in the New Year, number plates ending with odd numbers - one, three, five, seven and nine - will be allowed on odd dates while number plates ending with even numbers - zero, two, four, six and eight - will be allowed on even dates.

The restrictions will be in place from 8am to 8pm from Monday to Saturday.

The rule has to be followed by everyone, except for those who have been granted exemption.

Delhi is known for its wide avenues, but with more than 8.5 million vehicles in the city, the roads are choked with endless traffic snarls.

And reports say with 1,400 new cars being added to the city roads every day, the situation is going to get only worse.

Authorities say car emissions are a major contributor to pollution and curtailing their use will help clean the city air.

They want to encourage more people to start using public transport like the Metro and the bus or take to cycling.

The odd-even formula is among several measures aimed at reducing smog levels - the plan is also to shut some coal-fired power plants in the vicinity of the city and vacuum roads to reduce dust.

Who is exempted?

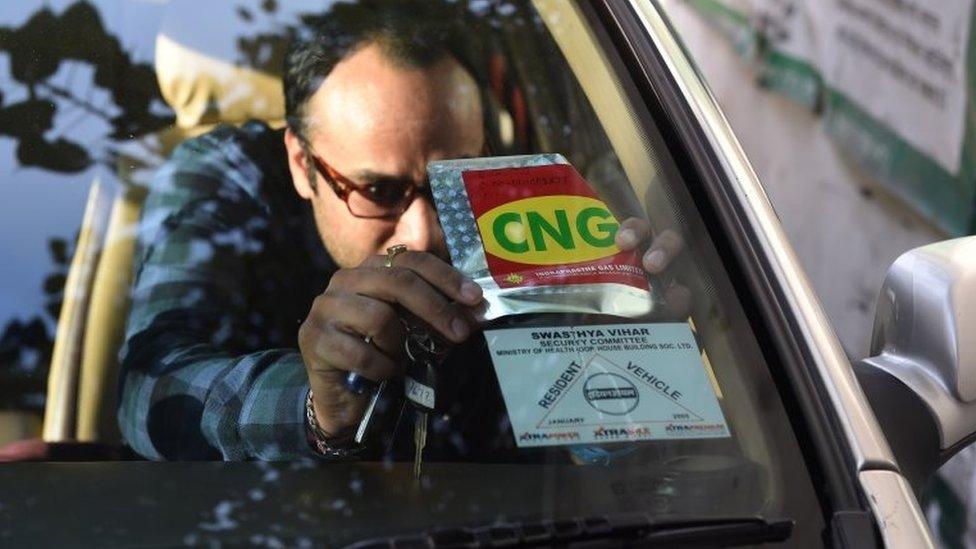

Private cars that use clean fuel like compressed natural gas or electricity are exempt

The list of exemptions is long:

All VIPs - including the president, vice-president, prime minister, all government ministers, several senior politicians, judges and foreign diplomats

Women drivers - alone or when they are driving with female passengers. Male children up to 12 years are allowed, but no adult men can travel in the car

Two-wheelers, which include motorbikes and scooters

Non-polluting vehicles - those that run on clean fuel like CNG (compressed natural gas) or electricity

Emergency vehicles - ambulances, fire engines, hospital and prison vehicles, hearses, enforcement vehicles or those belonging to paramilitary forces

Disabled drivers

Those on the way to hospital for emergency treatment - they will be allowed to go if they can "prove the emergency" to the traffic policemen

This long list of exemptions has caused much heartburn - the Delhi police chief has said enforcing the scheme will be difficult, external and the Delhi high court has asked the government to explain the rationale behind exempting women and two-wheelers.

How will the scheme be enforced?

Besides policemen, thousands of volunteers will be at traffic signals, telling the offenders "politely that they should follow the law"

Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kerjiwal has said the idea is to encourage people to use public transport more and to cope with the increased numbers, the government will be running 3,000 additional buses.

Schools have been ordered to remain shut until 15 January so that their buses could be used as public transport.

Car-pooling is being encouraged and the web-based taxi service Uber and radio-taxi service Meru have also launched pooling facilities.

Thousands of traffic policemen will be deployed to catch the violators and the offenders will have to pay a fine of 2,000 rupees ($30; £20) - rather steep by Indian standards where traffic offenders generally get away with a fine of 100 rupees to 400 rupees.

In addition, Mr Kejriwal's Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) has roped in more than 7,500 volunteers - they will man nearly 200 traffic signals, carrying placards to encourage people to follow the scheme. They will tell the offenders "politely that they should follow the law and give them a flower and ask them to go home", external.

What has been the public reaction?

The reaction to the odd-even plan has been mixed

Mixed.

The chief justice of India and the US embassy - though on the list of exemptions - have said they would carpool and follow the odd-even formula.

Many residents, sick of breathing the toxic air, have expressed their support and said they would join in to make the scheme a success.

Many others, however, are complaining about the inconvenience they would face getting to work - they point out the inadequate public transport infrastructure and poor last-mile connectivity.

The Metro and buses are already bursting at the seams and with millions more taking to public transport, overcrowding will get worse, they say.

Will it help clean the Delhi air?

Delhi traffic policemen are expected to have a tough time enforcing the odd-even car plan

A few months ago, Delhi introduced a "car-free day" on the 22nd of every month - on that day, cars are banned from one city district for a few hours and authorities say the air quality monitoring has shown a plunge in pollution levels in the area after the exercise.

They say they are confident that the odd-even formula, along with the other measures, will make a difference.

Critics, however, say it's too little because of the long list of exemptions.

The environmental group, Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), has welcomed the "emergency action to reduce vehicle numbers on the road" but questioned the absurdity of exempting two-wheelers, which account for more than 30% of air pollutants generated by the transport sector in Delhi, external, and women drivers.

Also, Delhi'ites are notorious for not following traffic regulations and there is talk already of how people will get around the ban with forged "sliding number plates" to fit the odd-even formula, how men might start dressing in drag, external to evade detection, how many may pretend to be sick and how many would rush to buy a second car.

Where did the idea come from?

In recent years, Beijing's pollution levels have worsened again

Car rationing has been tried in many countries around the world.

In 1989, Mexico's capital city introduced "hoy no circula" - roughly translating as "today, (your car) does not circulate".

Since then, similar restrictions have been tried in the Colombian capital Bogota, the Chilean capital Santiago, Brazil's largest city Sao Paulo, the French capital Paris and the Chinese capital Beijing.

Beijing's odd-even formula imposed ahead of the 2008 Olympics produced its best air quality in a decade - with a Chinese government study claiming that vehicle emissions reduced by 40%.

Indian authorities say they are hopeful of similar results.

In recent years though, Beijing's pollution levels have worsened again - a warning to authorities in Delhi that the measures will have to be sustained in the long run.

Will it be extended?

Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal has said he is committed to reducing pollution in the city

The Delhi chief minister has said if the policy causes too much inconvenience to the city residents, they will scrap it.

For the next fortnight though, all eyes will be on Delhi - the WHO survey of global cities last year said that besides Delhi, 13 of the most polluted 20 cities in the world were in India.

If the experiment succeeds in cleaning up Delhi's air, other cities may also be willing to try out the odd-even formula.