Pathankot attack: India-Pakistan peace talks derailed?

- Published

Six Indian soldiers died in the Pathankot attack

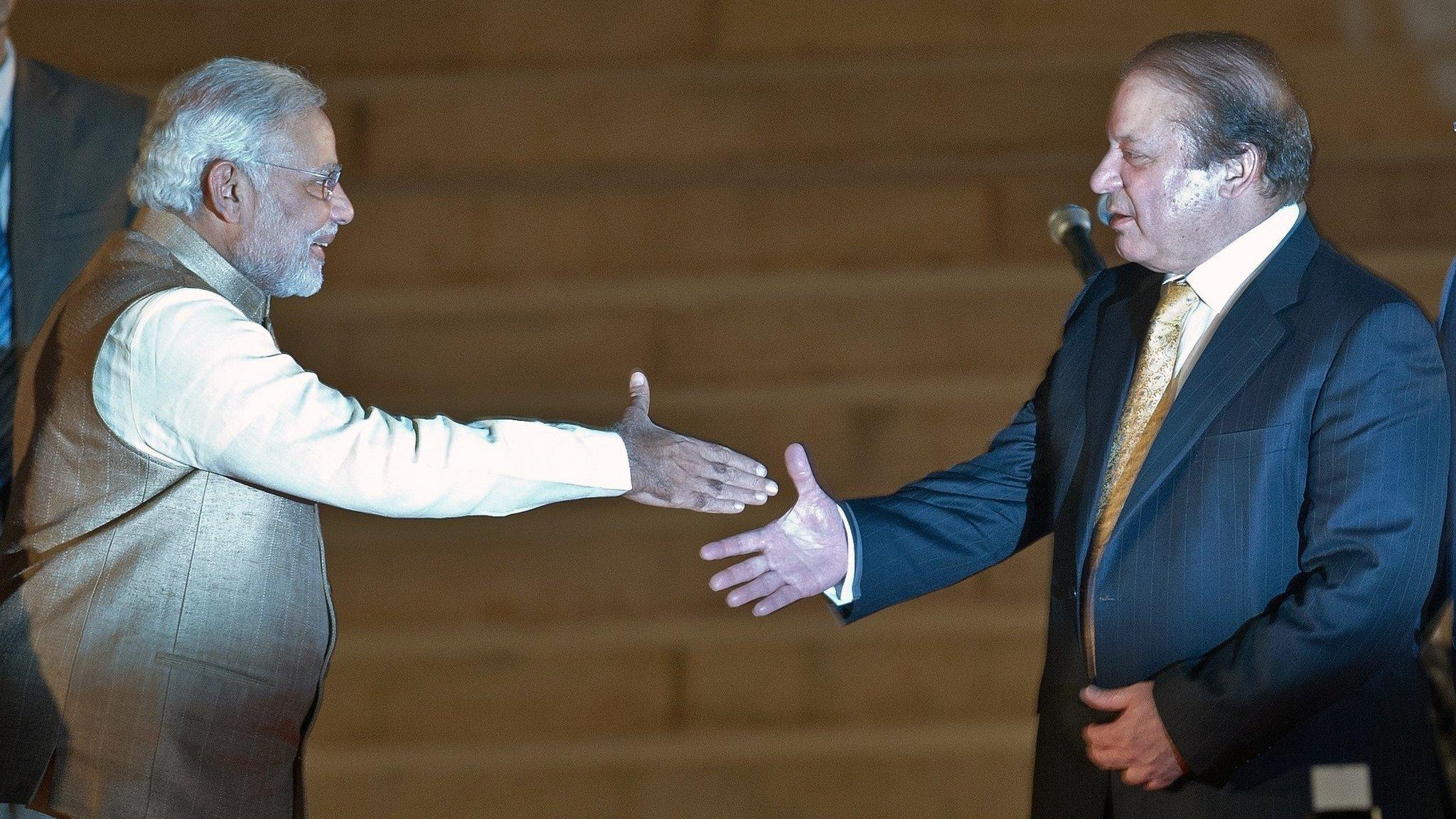

On Christmas Day, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a landmark visit to Pakistan to meet his counterpart Nawaz Sharif, the first such visit in over a decade. Two weeks on, and events have taken a disturbing, if predictable turn.

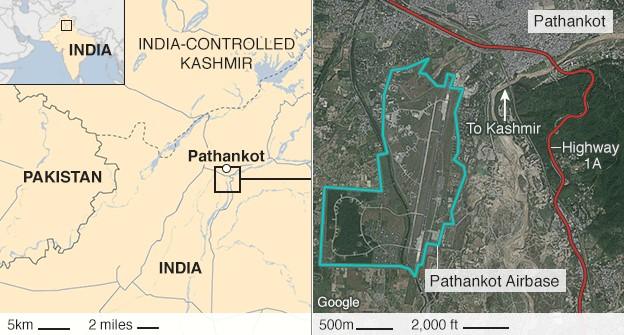

On 2 January, India's sprawling Pathankot airbase came under a remarkable four days of attack from a handful of gunmen. On 3 January, India's consulate in the northern Afghan city of Mazar-e-Sharif was besieged for over 24 hours. Then on 5 January, an explosion occurred near another of India's Afghan missions, in Jalalabad.

The two leaders had agreed that their foreign secretaries would meet in mid-January, and their national security advisers (NSAs) the next month. Indian officials were optimistic that Pakistan's powerful army - which famously torpedoed a rapprochement in 1999 by covertly sending troops into the Kargil district of Kashmir - was on board.

That assumption is now in doubt. Although the evidence remains uncertain, Indian officials have privately blamed the Pathankot attack on the Pakistan-based Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM), a militant group close to Pakistani intelligence which had been kept on a tight leash for several years.

Indian officials are sceptical of a claim of responsibility by the United Jihad Council, a confederation of Kashmiri jihadist groups, because the UJC's core members are not known to have carried out attacks outside Indian-controlled Kashmir.

Mr Modi (left) urged Mr Sharif (right) to "take prompt and decisive action against the terrorists"

Meanwhile, the Afghan attacks would be the seventh and possibly eighth such attacks on Indian diplomats there in under a decade, with even the United States attributing the most prominent - a 2008 bombing of the embassy in Kabul - to Pakistan's intelligence services.

Afghan insurgents have little cause to focus resources on Indian targets. It strains credulity to imagine that they do so in the absence of Pakistani direction. The timing is especially sensitive, as India is wary of China-brokered peace talks involving Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the Taliban - and the impact on India's long-term position in Afghanistan.

While a single incident within India could be written off as the work of autonomous jihadist "spoilers", concurrent attacks in Afghanistan and India are harder to interpret as such. At the same time, it is difficult to see how Pakistan's army could have planned an attack, if it wanted to, in the two weeks since Mr Modi travelled to Lahore, or even in the month since a fleeting Modi-Sharif meeting in Paris. Such attacks in the past have had much longer gestation periods.

What now for India? Mr Modi is personally invested in engagement with Pakistan and his advisers would certainly have accounted for the likelihood of such attacks in their decision to engage.

India's reluctance to break off talks is evident. When Mr Modi spoke to Mr Sharif on Tuesday, he reiterated the demand that Pakistan act on the "actionable and specific information" supplied; but he avoided blaming the Pakistani state. It is equally telling that Mr Sharif in turn praised the "maturity" of Indian statements. Notably, the two NSAs have also spoken to one another twice since Sunday.

This is an unusual, if welcome, level of cordiality in Indo-Pakistan relations in the aftermath of a major terrorist attack.

But there may yet be bumps in the road. Some Indian officials have suggested that if the scheduled talks do occur, they must focus entirely on terrorism. This will jar with Pakistan's belief that India's core concern, terrorism, should be discussed alongside Pakistani concerns, such as the Kashmir dispute.

One way of fudging the issue would be to bring forward the NSA talks, which would have focused on terrorism anyway, so they precede the broader discussion between foreign secretaries.

If JeM's role becomes clearer, India - cognisant of international and especially American eagerness to sustain India-Pakistan contacts - could even leverage the situation to push for pressure on Pakistan to clamp down on the group, recalling its modest success in doing so in 2001-2 during a similar crisis.

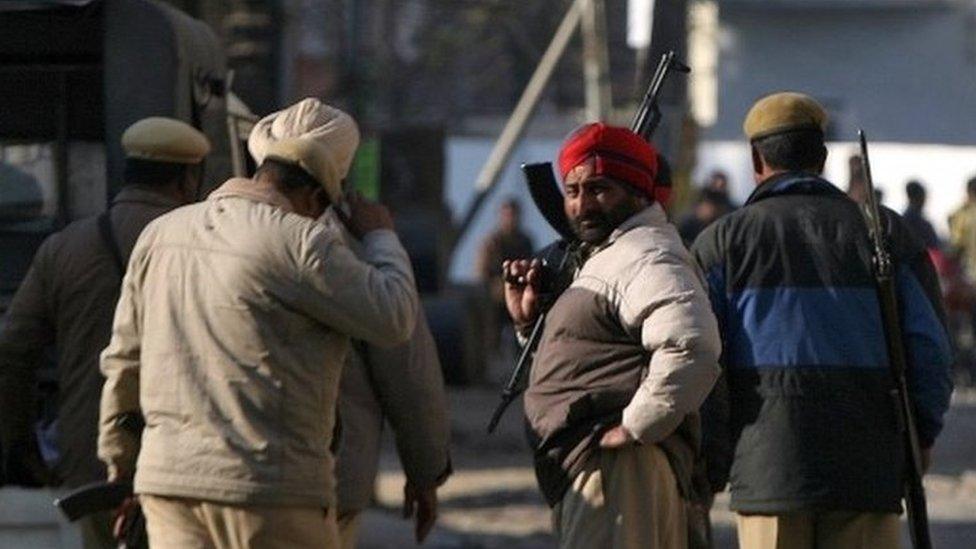

Indian troops battled the militants for nearly four days

The problem is that even if Mr Modi's outreach can survive this period of strain, there are limits to what it can bear. India got lucky at Pathankot. Its counter-terrorism response was, by some measures, catastrophic. Perimeter security was awful despite fortuitous advance warning.

A plethora of unsuitable competing forces - including ageing Defence Security Corps (DSC) personnel, close-quarters trained National Security Guards (NSG), and the Air Force's Garud commandos - operated with an uncertain chain of command. And a series of premature declarations of victory by characteristically loquacious ministers confused matters further.

The army, highly experienced in clearing operations over large areas, was bafflingly sidelined despite the proximity of several large units. Poor Indian border security and connections between drug smuggling and border guards also seems to have played a role.

Had the attackers exploited these failures and successfully destroyed "strategic assets" - India's term for the MiG-21 fighter jets and Mi-35 attack helicopters located at the base - or had they massacred family members of army personnel, as occurred at Kaluchak in 2002, a much larger crisis would have resulted.

Those behind Pathankot must have known this was a possibility. It presumably remains their objective. And India's counter-terrorism defences will remain highly uneven, at best. Such a crisis is therefore a near certainty. Yet the only actor seriously capable of clamping down on cross-border violence - the Pakistani military - is likely to remain disinclined to do so.

- Published4 January 2016

- Published25 December 2015

- Published27 July 2015

- Published5 October 2015