India's maverick 'frog man'

- Published

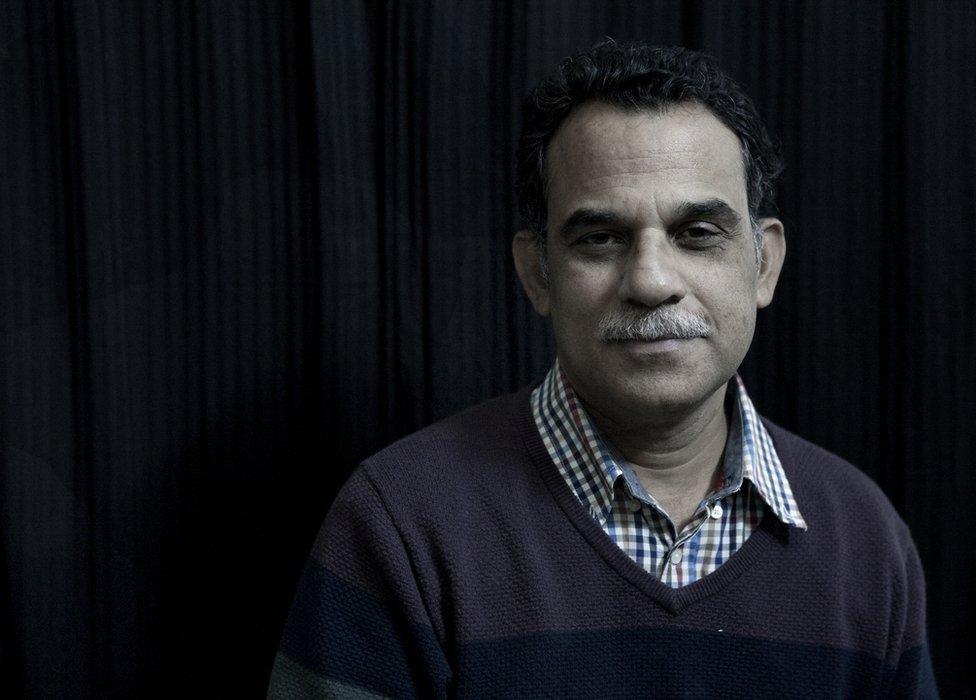

Dr Biju grew up in a remote village in Kerala

"Without this frog, I would be a nobody," says Sathyabhama Das Biju, sitting in his laboratory in Delhi University, on a cold overcast afternoon.

The phones haven't stopped ringing ever since Dr Biju and his team of scientists announced their latest discovery - an extraordinary tree frog thought to have died out more than a century ago. The usually quiet and cosy book-lined lab with a frosted glass door which says 'The Frog People' is unusually frantic.

But right now, the 52-year-old amphibian researcher - The Economist called Dr Biju the "closest thing Indian herpetology has to a celebrity" in 2011 - is talking about the purple frog, a brand new family of amphibians he discovered in 2003.

This bizarre, pig-nosed frog, found in Western Ghats, a mountain range and a biodiversity hotspot that runs along the western coast of India, uses shovel-like limbs to burrow the earth and live as deep as 20ft (6m) under the ground. National Geographic, external described it as a frog with a "chubby, purple body and pointed, pig like snout... and unlike any frog on earth".

The Indian purple frog that 'changed' Dr Biju's life

The tiny night frog, seen here sitting on a five rupee coin, is another of Dr Biju's discoveries

"People say it is a weird looking frog, but I find it beautiful. It looks like a turtle and sounds like a chicken. They are also very smart," says Dr Biju. They emerge during the first monsoon shower to mate, and the males call out to attract the females.

'Changed my life'

"This frog changed my life, it made me what I am today."

That was two years after the researcher published a controversial paper that claimed that up to 200 frog species were still undiscovered in India where the amphibian is generally associated with a pond frog or a common toad. "Many people said I was bluffing," says Dr Biju.

More than a decade later, the maverick researcher stands vindicated.

In the last 15 years, Dr Biju - called the frog man of India and the frog fanatic, among other things - and his team of scientists have discovered 89 of India's 388 frog species. He reckons there are some 100 species which remain undiscovered - enough to keep him working for a while.

Dr Biju and his team rediscovered this lost specie of bubble-nest frog after 136 years

Frog specimens are preserved in Dr Biju's laboratory

It has been a long, strange trip for Dr Biju.

He was born in a farming family in a remote Kerala village on the edge of a forest, which is now a small town. He grew up bathing cows, feeding chickens, living in nature and protecting the crops from the depredations of wild animals. He went to primary school - which doesn't exist now - late, around the age of 11. "Getting educated late actually helped," he says with a wry smile. "I spent a lot of time with nature, observing animals. This taught me more than any science books."

Dr Biju then travelled to Trivandrum to pick up a degree in botany from one of India's oldest colleges. He also finished a doctorate in plant evolution before landing a job as junior scientist with a state-run research facility. His job was to explore plants and find out more about their utility.

'Plants are boring'

"But plants bored me, I was not happy with them. I wanted to study something which moved," he says with a disarming childlike candour.

So Dr Biju used his modest salary to buy a camera and a motorcycle and began travelling into the forests in southern India and found that frogs drew him more than anything else. Along the way he did his second dissertation - this time on amphibian evolution and the conservation of the frog-rich Western Ghats - from a university in Brussels.

He believes he turned to frogs because Indians are obsessed with tigers, elephants, leopards - "our three most charismatic animals" - and birds. "We neglect our extraordinarily diverse bio-diversity. I have, at least, got people talking about frogs."

And how. Listen to Dr Biju talking about his discoveries, and you realise that he is no pedant, but a sprightly man of science who is, at once, erudite, energetic and passionate about his slimy subjects in equal measure.

Tell me about your most favourite frog discoveries, I ask.

Dr Biju has studied the behaviour of this 'dancing frog'

A tree frog discovered by Dr Biju in 2010

The meowing frog is among Dr Biju's discoveries

There's a meowing night frog, external with a "secretive lifestyle"; another one with a "unique parenting style" - both parents watch over the eggs until they hatch; a loud singing night frog he discovered in a cardamom plantation; and foot-waving dancing frogs, external with "bizarre courtship rituals".

Then there's the smallest Indian frog, less than 11mm (0.43 inches)-long which can sit on a coin.

And this week, he announced the golf ball-sized frog that lives in tree holes up to 6m (19ft) above ground, which may have helped it stay undiscovered.

Frogs have an extraordinary history of evolution of more than 350 million years, he adds, "possibly the oldest animal with a backbone, having witnessed five extinctions".

'Magical'

The Frankixalus jerdonii - as the latest discovery has been christened after Mr Biju's adviser herpetologist Franky Bossuyt - was a serendipitous discovery when the researcher and his students were digging in the day looking for frogs in Meghalaya state. As evening fell, Dr Biju says, they heard "a full musical orchestra coming from the treetops".

"It was magical.

"So we began climbing the tree. We went up 7ft and spotted the tadpoles. Much later we realised that we had stumbled on to a major discovery." Most tree frogs live closer to the ground.

Over the next seven years, the frog man and his students collected more specimens, compared it with other tree frogs around the world, looked at their behaviour, outer appearances, skeletal features, and sequenced their genetic code.

Then they identified the frogs as part of a new genus, meaning it has a new name. And they found an amazing quirk - females laid their fertilised eggs in tree holes filled with water, only to return after the tadpoles hatched, to feed them unfertilised eggs.

But the new tree discovery is a work in progress, says Dr Biju.

"How do they breed? Do they come down from the tree? Does the mother stay with the babies? We are still trying to solve a lot of unanswered questions."

The search for answers will continue, as will Dr Biju's amphibian journeys.

Every monsoon, the researcher and his students will trek to the mountainous rainforests of southern India and north-east to look for the frogs. (For a riveting account of an expedition, read this, external.)

Here is where the frogs, acutely sensitive to climate and habitat changes, are struggling to fight extinction. There are some 7,000 species of frogs in the world, and Dr Biju reckons half of them are on the verge of extinction.

Dr Biju's latest discovery is an extraordinary tree frog thought to have died out more than a century ago

Dr Biju's laboratory in Delhi university

"That is why we have to keep on working. All my discoveries are accidental. We don't plan on finding new frogs. You go out into the forests and spend time there."

Dr Biju says he has no other interests in life. The last time he went to see a movie was when his students dragged him to the theatre to watch Avatar. His wife has a doctorate in plant breeding and genetics. His two daughters aren't interested in frogs: they will possibly pursue careers in liberal arts and medicine.

"I have my friends and I have my frogs. I sometimes wonder what my life would be after frogs."