Viewpoint: Will 2016 be a turning point for free speech in India?

- Published

Arundhati Roy faces a contempt of court case over her reporting

In December, just before India's busy literary festival season swung into full gear, over a hundred journalists across the central state of Chhattisgarh were gathering for another round of protests.

They were demonstrating against the arrests, external earlier in the year of two local journalists, Santosh Yadav and Somaru Nag, in cases they called "false".

They had been raising their voices ever since August, and with Delhi's journalists adding their support, the state government finally agreed to set up an independent committee that might look into cases such as this.

2015 had been one of the harshest years in memory for India's journalists, and for free speech in general - local-language newspapers, reporters and stringers had faced everything from defamation suits to threats and detentions, and worse.

Reporters Without Borders, external tracked the cases of nine journalists who had been murdered in 2015 - the most dangerous beats were environmental and political corruption. In Nagaland, newspapers blanked out their editorial spaces in November - an unprecedented gesture, as a protest against military directives that threatened to crush free reporting in the media.

Rot and fear

The rot and the fear were not limited to journalism: 2015 was by any standards one of the worst years for free speech in India, with a sharp rise in defamation cases, sedition cases, majoritarian bullying and everywhere, an undercurrent of violence, a sense that mobs, or hired executioners, were never very far away.

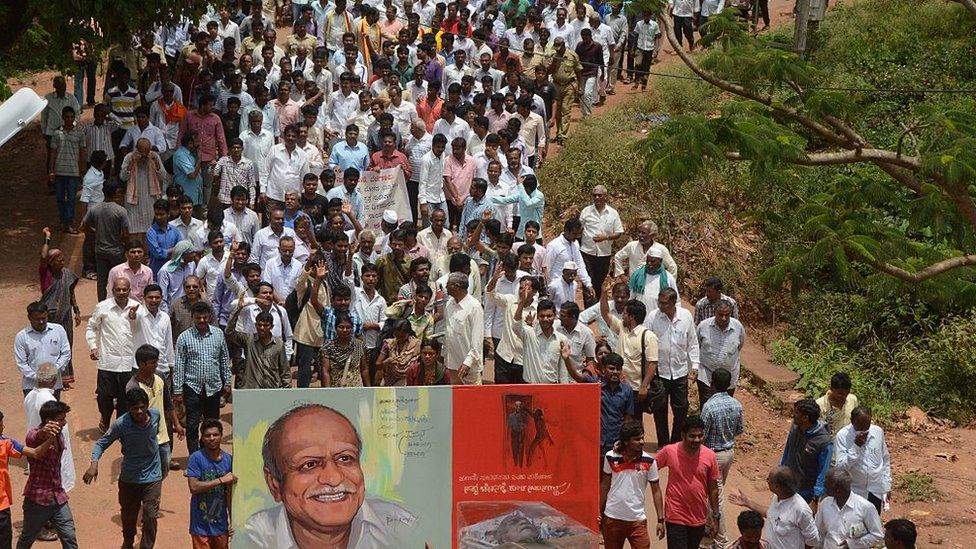

In the middle of the year, writers across India had returned their state awards after the Karnataka scholar MM Kalburgi was shot by two unidentified attackers in his own home.

This gesture of conscience - spontaneous and unplanned - snowballed into a surprisingly large demonstration of solidarity as hundreds of academics, scientists, film stars and historians joined in the protest against intolerance.

At some cost: senior government ministers called the movement a "conspiracy", and the rightwing's army of trolls attempted to bully the writers, sometimes brazenly spreading lies about them.

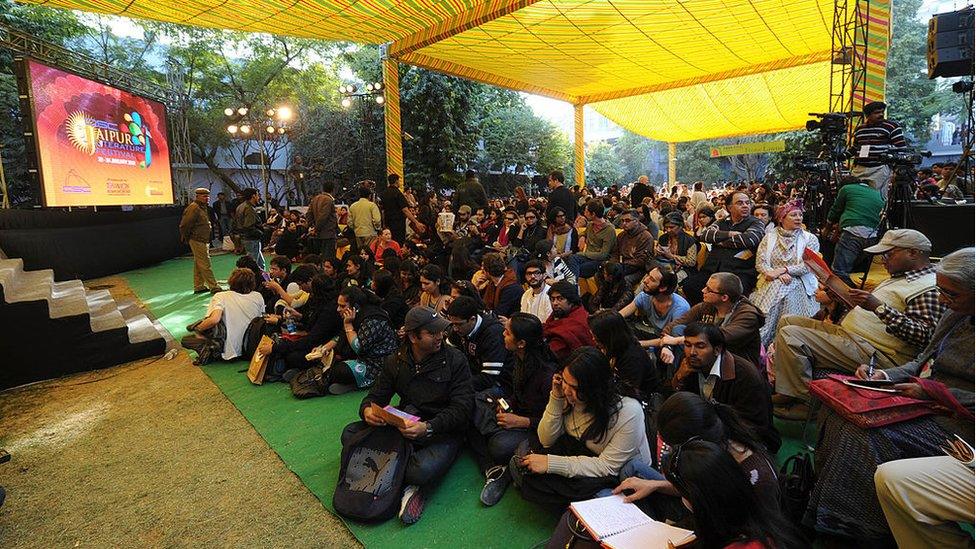

The Jaipur Literature Festival draws crowds in the hundreds of thousands

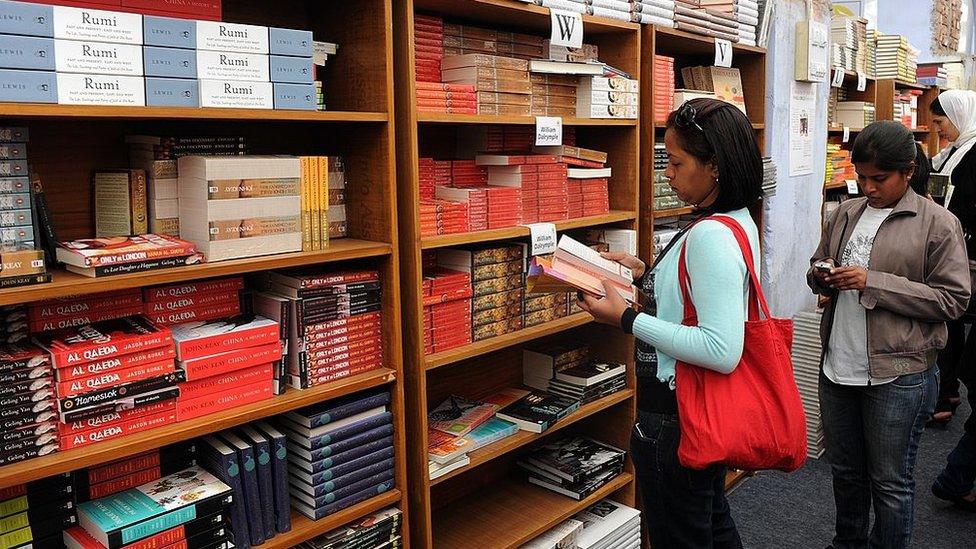

India had also seen an enormous and unsuspected appetite for books

It is impossible not to believe that 2016 will be a turning point for India and free expression in the subcontinent.

We could go under, losing more and more essential freedoms as writers, performers, environmentalists and citizens are caught in the crossfire of pressure from the state, as outspoken voices choke in the pollution caused by bad laws, or succumb to the rule of mobs, thugs and the deliberate violence unleashed by religious and political leaders.

Or we could see a steady fight wresting back these basic freedoms and demanding them as universal rights, not just rights for the relatively small world of India's English-speaking writers and journalists.

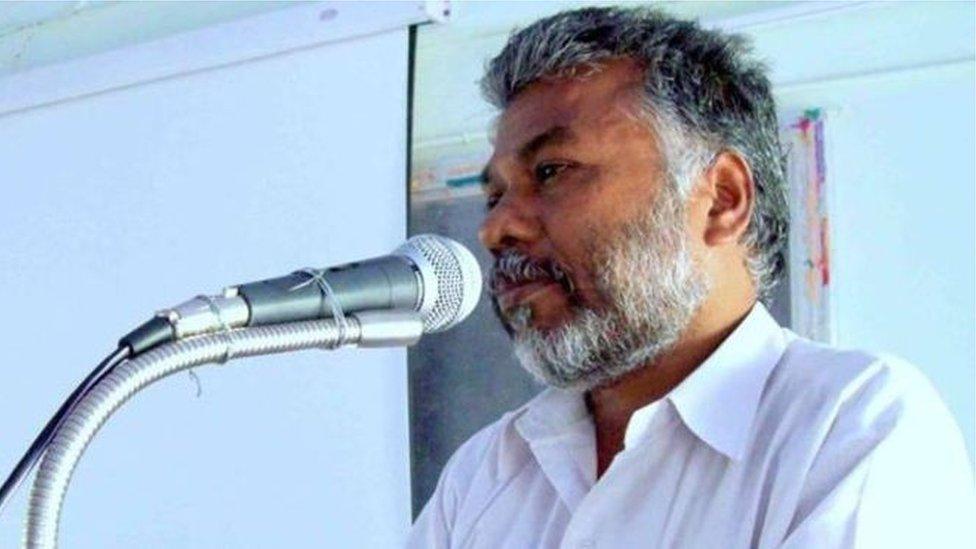

There is a wider sphere that connects the folk singer Kovan,, external arrested in November under sedition laws in Tamil Nadu for lampooning the government, with Huchangi Prasad, external, a young Dalit writer from Karnataka who had been beaten up in October and threatened for his writings on caste and religion, and the well-known writer Arundhati Roy, external, who faces a contempt of court case this month yet again over her reporting, on flimsy grounds.

Appetite for books

2015 had seen a landslide of alarming and tragic events. But these past years in India had also seen an enormous and unsuspected appetite for books, a nascent fascination with authors, bestselling and otherwise.

The single biggest indicator of this was the profusion of literary festivals around the country - over 75 at last count, with the largest of them, the Jaipur Literature Festival, external, drawing crowds in the hundreds of thousands.

They could be spectacles with film stars, cricketing heroes and politicians grabbing the headlines rather than writers, but they were also increasingly one of the few spaces where writers in English and Hindi could meet authors and publishers whose medium was one of India's many other languages.

At the Hindu Lit For Life i, externaln Chennai, I had the chance to hear Kannan Sundaram speak.

Mr Sundaram is the publisher of Perumal Murugan, the writer who erased himself by announcing, "the death of the writer, Perumal Murugan".

The murder of Malleshappa Kalburgi set off an unusual movement with little precedent

He had been subjected to legal attacks, threatened, and in this deadly game of chess, where writer after writer was accused of provoking acts of organised violence, he had chosen to take himself and his books off the chessboard. Mr Sundaram spoke on the challenges in publishing, a subject on which he was, by any standards, an expert.

But on the drive to Jaipur, I was thinking about another incident, an apparently minor one in the present landscape of murders, thuggery, violent intimidation.

Just before the New Year, novelist and academic Saikat Majumdar had one of his short stories abruptly pulled from the Mint newspaper's end-of-the-year fiction special.

'Violence of words'

Majumdar got in touch with Delhi's nascent PEN chapter to ask if there was anything the group could do to help. The publication was within its rights not to carry his story, but the reason they gave sounded like self-censorship: their lawyers had said the story contained too much "violence of the words".

The magazine Caravan offered to print the story instead, with an explanatory note, and Majumdar's The Father of Man , externalcame out in its January issue.

The incident left a question mark hanging in the air: were we measuring sentences, now, for the violence of their words, and if so, what was the violence ration? What did editors consider an acceptable, under-the-radar amount of violence for words to bear?

The festivals felt, this year, somewhere between an escape from the violence that was bubbling up across the country along fault-lines of gender, caste, race and political allegiance, and something else, something more serious.

On the final day at Jaipur, I listened as Nirupama Dutt, the poet and biographer, shared her memories of the murder of Pash, the Punjabi poet, in 1988, another era of turbulent change.

I felt lucky to be on a session with Ashok Vajpeyi, Uday Prakash and CP Deval, to listen to them talk about what it meant to be a writer in a time of storms, how the writer's responsibility was not separate from his or her duty as a citizen.

Perumal Murugan is one of the finest writers in the Tamil language

In Jaipur, we spoke about the rise in defamation suits (48 filed in 2015), and what it meant for corporates and state governments to use this law to muzzle critics; about the contempt case against Arundhati Roy; about the rise in sedition cases (14 filed in 2015 against 35 respondents) making it a crime to question your country.

Roy's trials were bookended by the plight of other writers, journalists, environmentalists, that was how greatly the times had changed.

There are so many kinds of violence.

There is the violence of the word that people fear because it holds up a mirror to what is happening in India today; there is also the violence of not listening to the words of those who have borne the harshest brunt of censorship, of dismissing their struggles and trials without giving them equal weight.

Arundhati Roy is fighting a monstrous and unjust battle, but as people speak up for her, they must not erase the others who fight the same battle, too.

- Published15 January 2015