Is Narendra Modi's government unravelling?

- Published

Mr Modi has remained silent on the recent unrest

A week is a long time in politics, and what happened in India last week has not exactly covered Narendra Modi's government in glory.

Many believe the government whipped up needless nationalist hysteria by sending the police into the prestigious Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) and arresting students under India's discredited colonial-era sedition laws.

It levelled allegations against the students on the basis of an allegedly doctored video a, externalnd a fake tweet, external. An unapologetic commissioner of police actually asked the students to prove their innocence, external.

As if this was not enough, Mr Modi maintained a baffling silence over the shameful attack on students and journalists by party-backed lawyers inside and outside a court. A lot of this violence happened within a mile of Mr Modi's office and his home ministry office.

Elsewhere, journalists and lawyers working in the Maoist-affected areas of BJP-ruled Chhattisgarh state were forced to pack up and leave, external, allegedly under pressure from the authorities.

At the well-known Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), BJP supporters kicked up a storm over beef being allegedly served in the college canteen, external, a charge that the university denied. And 19 people died in violent caste riots in BJP-ruled Haryana.

'Assault on free speech'

Mr Modi's peace initiative with Pakistan - he paid a surprise visit to his counterpart Nawaz Sharif in December - appeared to be in tatters after militants stormed an institute in Kashmir.

Talks between the two countries have stalled anyway after last month's attack on an air force base near the Pakistan border. Mr Modi has promised growth and jobs, and last year India outpaced China in terms of economic growth, though some analysts say India still doesn't 'feel' , externallike a 7% economy.

But what has rankled most are the campus arrests. Critics have condemned them as an assault on the freedom of expression. Yet government ministers have refused to back down, vowing to punish what they describe as "anti-national elements".

Students of a leading university have been arrested for shouting anti-national slogans

Many believe that whipping up nationalism is a 'risky gamble' for the government

Commentators have described the student arrests as a "national embarrassment", external and a "self-goal", external for Mr Modi's government. A columnist wrote that sending the police after the students was like "swinging a battle-axe to crack a nut"., external

The government, said another analyst, was "seeking out conflict", external rather than resolving it. The New York Times wrote trenchantly that Mr Modi and his political allies were "determined to silence dissent", external. Rights watchdog Amnesty International, never a friend of Mr Modi, has joined in, blaming his government for contributing to a climate of growing intolerance for dissent, external.

Mr Modi has so far preferred to remain silent - even on his favoured Twitter - about the rising frenzy over nationalism being stoked by his party.

Inflection point

Much like former prime minister Indira Gandhi, who used to blame the "foreign hand", external for her government's travails in the last few years of her reign, Mr Modi, who secured one of the biggest mandates in India's history last May, said recently that conspiracies were being hatched, external to destabilise his government.

"I find his behaviour increasingly odd," historian Ramachandra Guha told the Financial Times.

It is not clear whether the last week could turn out to be an inflection point in the history of Mr Modi's government. A week of mass protests in Delhi in December 2012 following the death of a woman who was gang-raped turned out to be such a turning point for the last government.

By the time Mr Modi's taciturn predecessor Manmohan Singh appealed for calm, his Congress party had completely lost the battle of perception.

On the eve of its second anniversary, Mr Modi's government, according to one commentator, could well have already sown the seeds of defeat, external.

Caste riots have rocked BJP-ruled Haryana

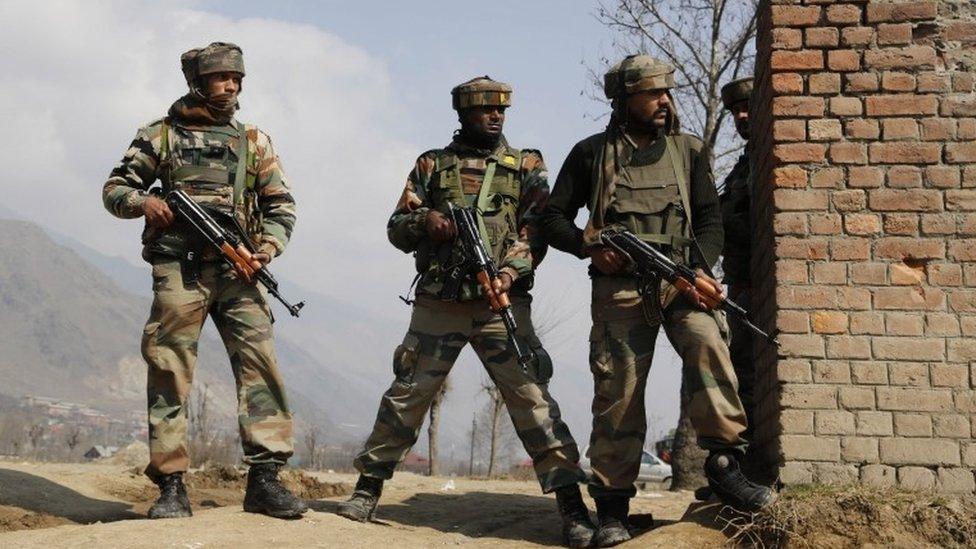

Militants killed five soldiers and a civilian in an attack in Kashmir

But such pronouncements may well be premature.

A recent opinion poll , externalshowed that although his popularity is fading, Mr Modi remains twice as popular as his rival Rahul Gandhi of the main opposition Congress. Mr Gandhi's feeble party and the regional opposition still remain, according to many, Mr Modi's greatest advantage.

Also, some believe that the current climate of confrontation actually helps Mr Modi and his Hindu nationalist party.

"This helps the BJP to move to the plank of ultra-nationalism. They are saying that India is threatened by anti-nationals, people who don't agree with us or vote for us," says Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, who has written a biography of Mr Modi.

'Bad for democracy'

"In one stroke everyone ranging from liberals to social democrats, parliamentary communists to ultra-leftists have been clubbed together as being anti-nationals. They are saying everybody has ganged up against this nationalist government."

Sudipta Kaviraj of Columbia University has written that India's economic growth may have led to rising nationalism among a section of its people. Dr Kaviraj says six decades of economic growth have produced a "relatively large and economically powerful and politically assertive modern professional middle class who support a strong nation state as a precondition for further economic growth". A substantial section of this urban middle-class continues to back Mr Modi for his muscular nationalism.

It is not clear, however, whether the idea of a less pluralist Hindu nationalist state is finding any buyers beyond a few northern and western Indian states. More importantly, India's villages end up deciding the fate of its governments.

Two years of drought, crop failures and declining rural incomes have left many farmers frustrated with Mr Modi's government. Triumphal nationalism may not be enough to stir them into voting for him.

Also, as Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay says, nationalism is always a dangerous gamble. "It sends out the signal that you want to remake India. It is bad for the health of our democracy and it is bad for India's image."