Why women are worst hit by India's farm crisis

- Published

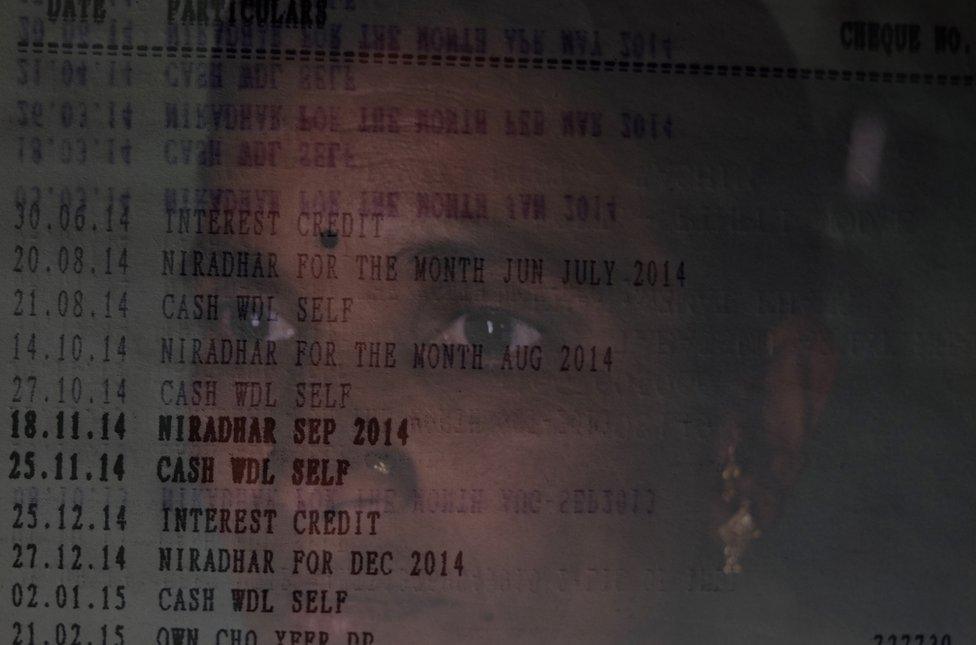

Mandha Alone suffered from depression after her debt-stricken husband took his life

He tried to take his life for the first time in 2009.

Mukunda Wagh, a farmer, consumed pesticide in the cow shed at his village home in Maharashtra's Washim district.

Then he collapsed, frothing at the mouth, and lay unconscious until his wife, Babi, found him. She rushed him to a hospital, where doctors washed his stomach and saved him.

Three years later, in May 2012, Wagh's luck ran out.

The soybean crop on his two-acre farm had failed and he was drowning in a debt of 60,000 rupees ($890; £631), borrowed from friends and relatives. Villagers found his lifeless body outside a local gas plant. He was 38.

'Not so fortunate'

"Some say he drank himself to death, others say he was electrocuted. His body had turned black. I was at my parents' place when this happened. My children said, if I had stayed at home, their father wouldn't have taken his life," says Mrs Wagh, 38.

Over four years, Mrs Wagh has rebuilt her family - she has worked long hours, tilling the family plot and working on other people's farms; sent her son and daughter to polytechnic; bought livestock, repaid most of her husband's loan. Low interest loans from self-help groups have been a lifeline.

"I am lucky. Other widows are not so fortunate," she says, sitting in her tin-roofed home in Malegaon village.

Archana Burare had to leave her farmer husband's home after he killed himself

...and her three-year-old boy - carrying his dead father's picture - needs expensive treatment for an ailment

One of them is Archana Burare, a 22-year-old widow, who now lives with her ageing parents and her baby boy in a village in Washim.

When her husband took his life after consuming pesticide in 2014, her in-laws abandoned her and locked up their home, forcing her to return to her landless father and homemaker mother.

Mrs Burare was 19 when she got married. Her husband had taken a 12-acre farm on rent after borrowing 50,000 rupees, and begun growing rice, groundnut and soybean. The crop was good the first year, and she also worked at another farm, and things were going fine.

"Then the rains stopped and the land dried up. The well ran out of water and the crops failed."

Mounting debt

The family went into a downward spiral. Her husband, she says, began drinking and beating her up. Then he broke his leg in a road accident, and could not afford an expensive private surgery to set it right. Meanwhile, the debts kept mounting: 25,000 rupees for her sister's marriage; another 20,000 rupees for the failing farm.

"I had gone to my parents' place for a break. He was alone at home when he drank pesticide and killed himself," says Mrs Burare.

"I did not get any compensation [from the government] because the land did not belong to my husband. My in-laws do not keep in touch."

Babi Wagh has rebuilt her life by taking low interest loans from self-help groups

Geeta Sudhakar Kale says she lives to pay off her dead husband's debts

Mrs Burare works as a cook at a government childcare centre for a salary of 850 rupees a month, but she hasn't been paid for the past eight months. Her widow pension is still stuck in the bureaucracy. She struggles to feed her extended family by working on other people's farms.

"I am trying to secure my family a bit, buying a few goats and a buffalo after taking some loans from self-help groups. My three-year-old son had an accident, and every check up at the private hospital is expensive. Government hospitals are crowded, it takes three days to get a scan."

Crop failures

According to one estimate, more than 3,000 farmers in Maharashtra have taken their lives every year between 2004 and 2013. Last year, as many as 3,228 farmers took their lives, the highest in the last 14 years, external, a government minister informed the parliament recently. Widows of 1,818 victims were paid compensation of 100,000 rupees each; the rest were found to be ineligible.

The vast, rain-fed farms of Vidarbha region spread over 11 districts in Maharashtra are the worst affected.

Cash crops are expensive to grow and a global commodities downturn has meant a drop in demand and declining farm incomes. Access to formal credit is scanty, so farmers are forced to borrow at usurious rates from private lenders to buy seeds, fertilisers, water pumps, and pay for a marriage in the family. Two successive poor monsoons have led to some nine million farmers in the region facing near-drought conditions and crop failures.

Nine million farmers in Vidarbha have been affected by two consecutive droughts

That's not all. It is not easy for the widows to be eligible for compensation: tangled land deeds mean ownerships of plots are often disputed - there are some 80 cases related to property disputes after farm suicides in four districts - and payment is denied if alcohol is found in the viscera of a dead farmer. The paltry widow pension can take ages to process.

"The widows are the worst affected. Single women face discrimination in patriarchal village households anyway. If they are widowed, they are often thrown out, deprived of their land, and their children's future is jeopardised," says Kishore Tiwari, a prominent farm activist heading a government panel to curb suicides.

'No future'

Mr Tiwari reckons 60% of some 10,000 farm widows in the Vidarbha region have received no compensation. What's keeping them going are dozens of non-profit and self-help groups networked to NGOs like Kisan Mitra (Farmer's Friend) which are counselling the widows, offering soft loans, making them aware of their property and legal rights and protecting them from sexual harassment.

The suicides mirror the state of India's ailing farms, which account for 14% of India's GDP, but on which more than half of its more than a billion people depend on for an uncertain living. Many farmers are simply not earning enough.

After the soybean and cotton crop on his three-acre plot failed, Mandha Alone's husband, Sharad, borrowed money to buy an auto-rickshaw, while she worked on the parched farm in Wardha district.

But, in 2011, he was injured seriously in a road accident, and had to sell his wife's jewellery and some of his land and take a loan of 200,000 rupees for a series of surgeries. He began defaulting.

"That completely broke him. He drank heavily, beat me up. Then on the day of Holi (festival of colours) in 2013, he simply walked into a river near our village and drowned."

Mandha Alone says there is 'no future' in farming

Mrs Alone says she went into a depression for a year. She was not eligible for compensation because the autopsy found liquor in Sharad's body. Then a self-help group arrived at her door and gave her a small loan to buy a sewing machine. Now she stitches clothes, works on other people's farms, and rents out the family plot.

Life continues to be hard, and her husband's debts remain unpaid.

"I have told the bank and the debtors that I cannot pay anymore. I tell them, take the responsibility of my children and do what you want to do," says Mrs Alone.

"There's no future in farming anymore. In the villages, farmers are driving auto-rickshaws, working in brick kilns. Their daughters are sitting at home because they don't get good grooms.

"If you come here in 10 years time," says Ms Alone, "you will see many, many more widows."