Viewpoint: Can India-Pakistan cricket promote peace?

- Published

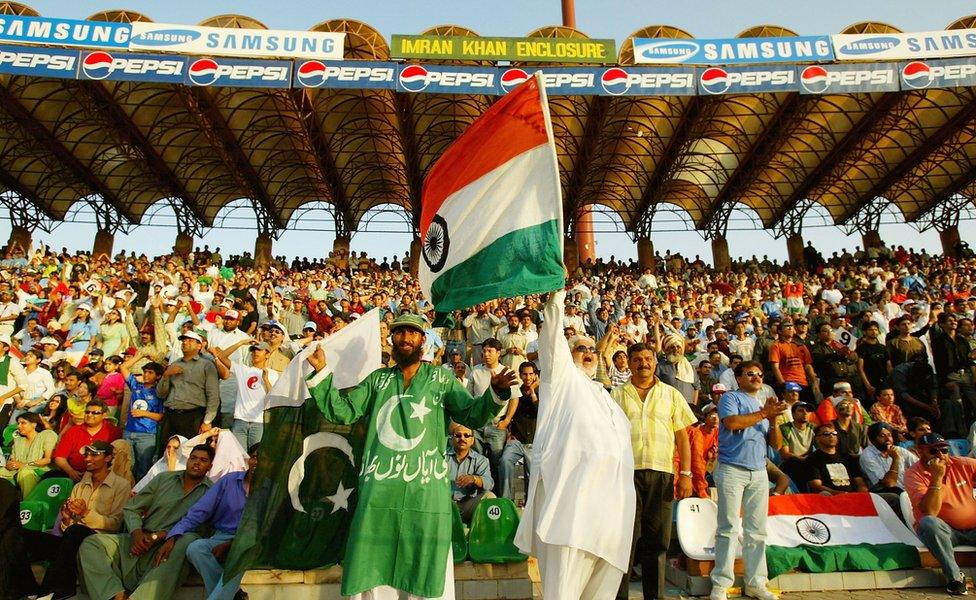

Pakistan allowed thousands of Indians to cross the border in 2004 to watch a series between the two countries

So India and Pakistan will play each other again on Indian soil, this time in the World Twenty20 cricket tournament.

Saturday's match will take place in Kolkata (Calcutta), having had to be shifted from picturesque Dharamsala because the chief minister of Himachal Pradesh state felt the families of Indian soldiers from his state would not welcome a game, external with the "enemy".

The Pakistanis nearly did not come at all, out of fear for their security.

The question of whether, amidst all the strife that besets the two countries' cricketing relations, a mere sport can bring them together, is at one level easy to answer: No.

Sport can sublimate many emotions, but it cannot be a substitute for geopolitics. Cricket can be an instrument for diplomacy, not an alternative to it.

After all, six decades of cricketing ties have done little to promote good relations between the two antagonists.

Victim of politics

If anything, the game has been a victim of politics, as proved by the 18-year gap in cricketing relations between the two countries from 1960 to 1978, the dozen-year hiatus in Pakistani Test tours of India between 1987 and 1999, and the current stalemate, brought about by the 2008 Mumbai attacks, external and sustained by subsequent incidents.

The basic challenge to "normal" cricketing relations lies in the nature of partition, which carved a Muslim state out of India. In Pakistan, cricket is expected to bear a particularly heavy burden as the embodiment of national pride against the larger (and more powerful) neighbour from which it seceded.

The instrumentalisation of cricket in the service of a militarised nationalism, especially against India, is a feature of Pakistani cricket.

So are explicit evocations of a religious mission (as when Pakistan's then captain, Shoaib Malik, publicly thanked "Muslims all over the world" for their presumed support for his team in the 2007 World Twenty20).

The contrast with India's multi-religious, multi-ethnic and commercially-driven cricketing culture is striking, and significant.

India have never lost to Pakistan in any World Cup

There was a 18-year gap in cricketing relations between the two countries from 1960 to 1978

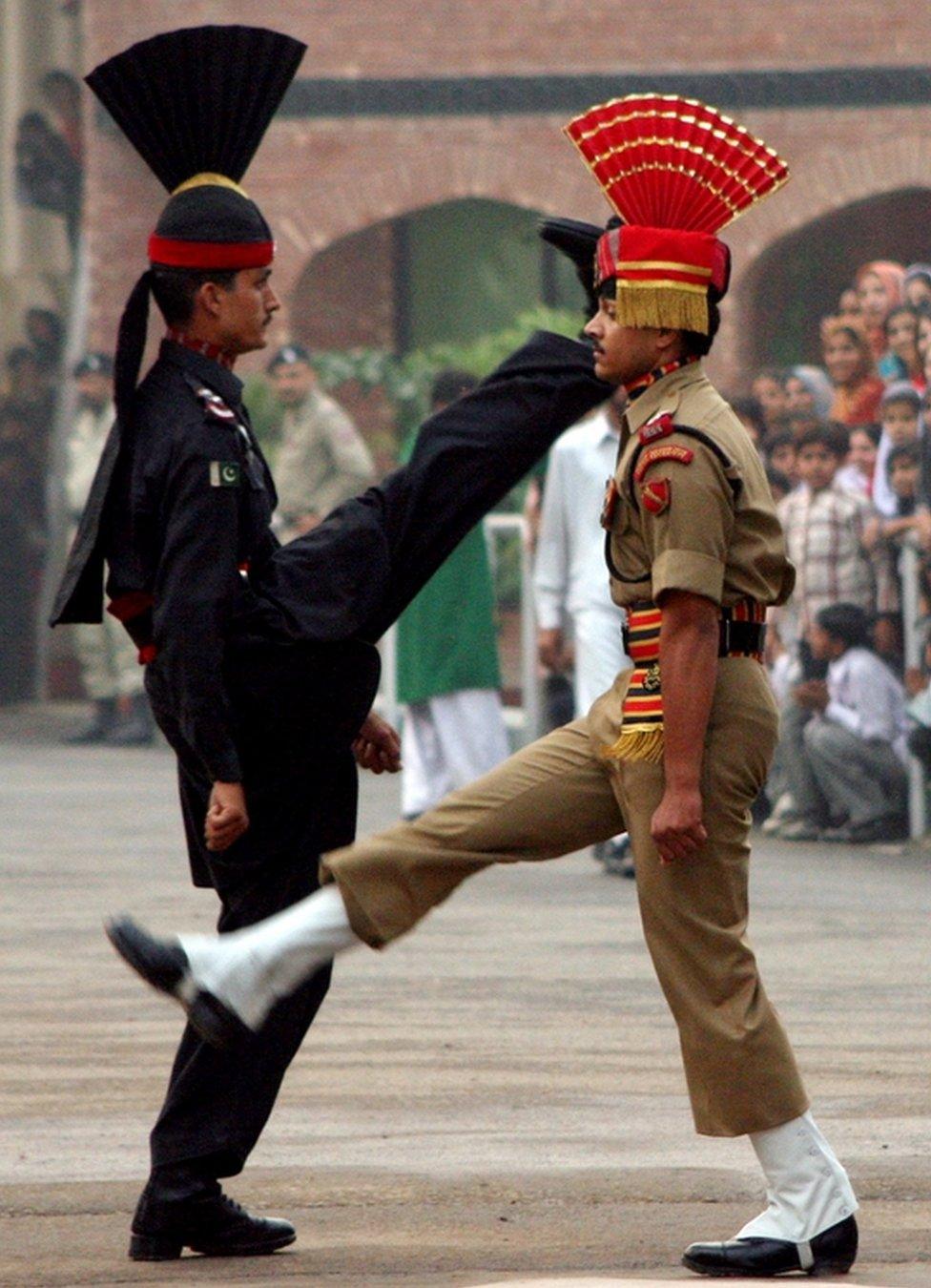

These are two countries whose soldiers have frequently shot at each other, where border tensions have erupted into war, and where the result of a cricket match can prompt a soldier to unleash a volley of celebratory or intimidatory fire on the Line of Control, the de facto border.

Above all, this is a region where the alleged fomenting of terrorism in India by Pakistan and (in Pakistani eyes) the "sufferings" of Muslims in India creates in each side a "moral obligation" to teach the perpetrators a lesson on the cricket field.

No other cricketing rivalry in the world has to contend with such a perverse mixture of elements sharpening the keen edge of competition between them.

Against such a background, it is expecting too much for cricket matches between India and Pakistan to remain mere sporting spectacles. As activist and philosopher CLR James has so memorably written, "what do they know of cricket who only cricket know?"

The two sides played each other in the 1999 World Cup in England while the Pakistani-instigated war over Kargil in Kashmir was going on: on the very day of India's 47-run victory, six Pakistani soldiers and three Indian officers were killed.

Healing capabilities

And yet there is a good argument to be made for the healing capabilities of cricket.

When India embarked on a peace offensive with its 2003-04 tour of Pakistan, Islamabad, for the first time in five decades, allowed thousands of Indians to cross the border on "cricket visas".

They were greeted effusively by ordinary Pakistanis: to be an Indian in Lahore or Karachi those days was to be offered free rides, discounted meals and purchases, and overwhelming hospitality.

It was said, not entirely in jest, that large numbers of Pakistanis were going about pretending to be Indians in order to avail themselves of these benefits.

But less than five years later came the horrors of the Mumbai attacks.

The first cricketing casualty (aside from the Champions League scheduled to be played in Mumbai itself the week after the attacks) was the planned Indian tour of Pakistan in January 2009.

'Cricket affords one of the best ways of getting the two countries to engage with each other constructively'

Indian fans celebrate as a Pakistani cricket falls during last year's World Cup game in Australia

As India's then sports minister, MS Gill, remarked in calling off the government's permission, "You can't have one team coming from Pakistan to kill people in our country and another team going from India to play cricket there."

Since then, the two countries have hardly played each other (except in international tournaments like the World Cup, a single charity game, and one solitary one-day series in 2011); and Pakistani players have not participated in subsequent editions of the Indian Premier League (IPL). Politics has clearly again trumped cricket.

So where does this leave the prospects for cricket promoting peace between these sibling nations entwined together by history with bonds of paradox?

For many years now the talk has been of war, militancy, terrorism and even of a nuclear threat. Indian politicians routinely ask how India could play cricket with a country that supports terrorism against us.

Many ruling party MPs, and the Hindu hardline Shiv Sena party, object to any sporting relations with Pakistan.

'War by proxy'

When a thaw occurs, cricket matches will instantly follow. But there's the rub: cricket will follow diplomacy, not precede it.

Even the warmth of 2003-04 was not a cause of better relations between the countries, but a reflection of it. And when things are unpleasant between the governments, matches that take place at times of tension, as with the World Cup encounter during Kargil, mirror the antagonism; they do not cause it.

Yet the tendency to see these matches as warfare by proxy is also unfortunate.

Cricket is a sport; a cricket team represents a country, it does not symbolise it. To ask cricket to bear a larger burden than any other national endeavour is palpably unfair.

Yet cricket is selectively being made to pay the price of Indian anger against Pakistan.

We have not imposed sanctions on that country, withdrawn ambassadors, stopped trade with them, or even banned their movie stars and singers from practising their profession in India.

But the one activity being singled out for opprobrium is the playing of cricket.

Pakistan's cricket team is popular in India

Six decades of cricketing relations have done little to promote good relations between the two antagonists

That's unfair.

I happen to believe that we need to engage Pakistan across a variety of fronts, and I am strongly in favour of people-to-people contacts with regular Pakistanis to balance the influence of the military and the mullahs.

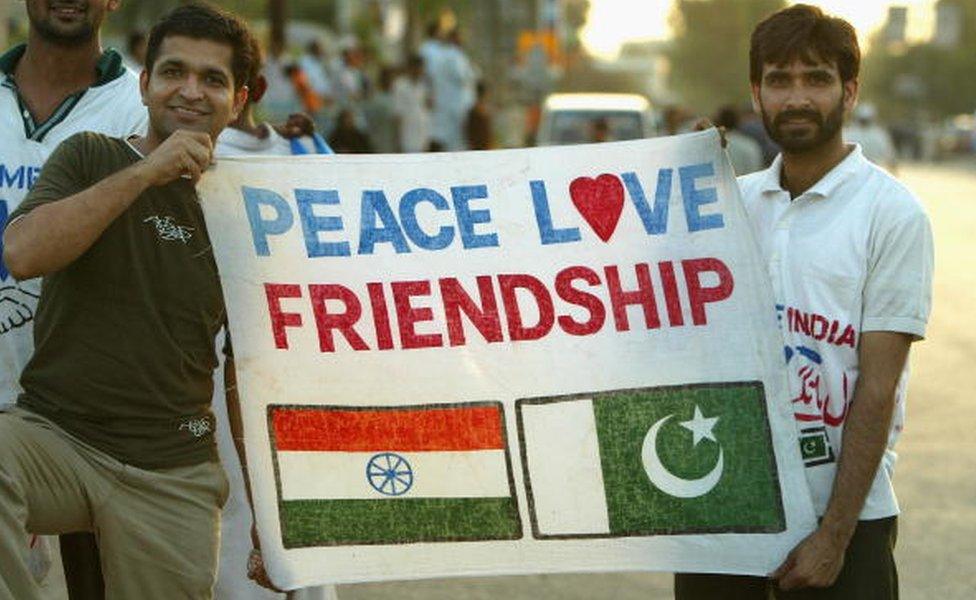

Cricket affords one of the best ways of getting the two countries to engage with each other constructively, and the two peoples to think about each other's talents and not their prejudices.

Cricket has been, and can be, an instrument of policy-makers determined to send a broader message to the general public.

But the policy issues remain unresolved, and till they are, cricket remains above all a sport, not "war minus the artillery".

So let us enjoy a good game of cricket on Saturday.

India have never lost to Pakistan in any World Cup; Pakistan have never lost to India at Kolkata's Eden Gardens.

One way or the other history will be made, and it is just as well that it will only be of the cricketing kind.