The man who helps a village through uncomfortable questions

- Published

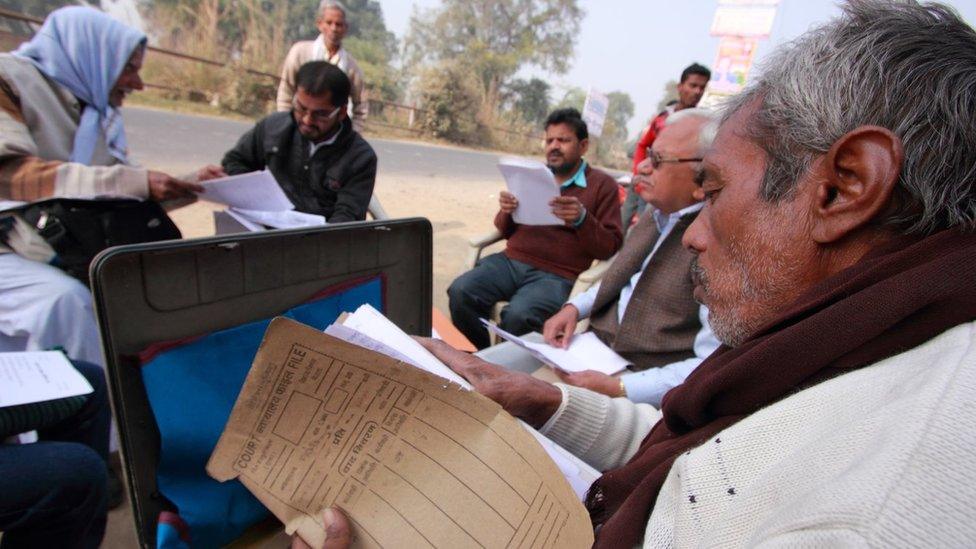

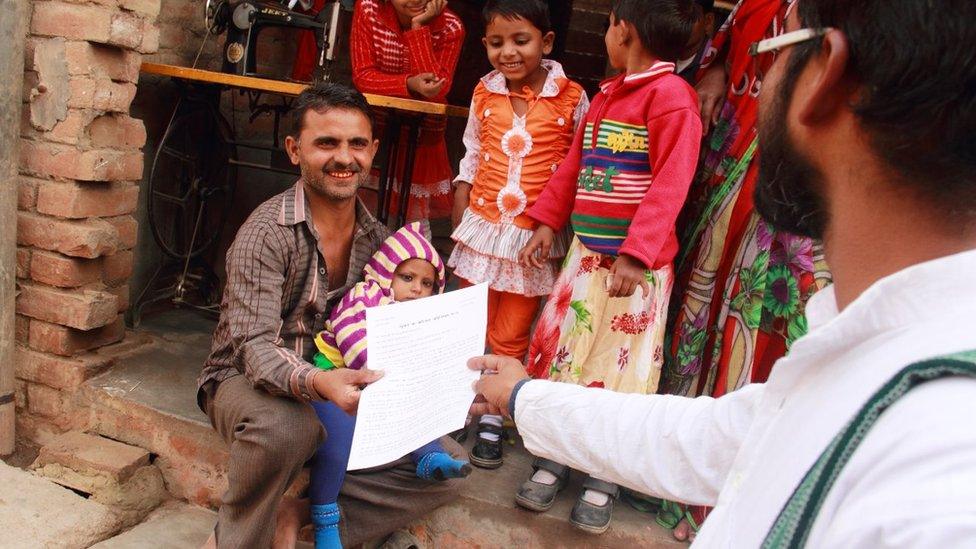

KM Yadav's tea shop doubles up as his office

KM Yadav has helped hundreds of Indian villagers access crucial government information that has helped them claim their benefits and rights. Vikas Pandey meets him at his "office" in Chaubepur village in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh.

Mr Yadav is patiently listening to a group of villagers as he serves them hot tea from his stall.

This tea stall is indistinguishable from the many others dotted across India's towns and villages - three mud walls and a thatched roof, with just enough space for 10 chairs and a few tables for people to sit.

But that's where the similarities end.

This stall is also a makeshift office, where Mr Yadav, an activist armed with India's Right to Information (RTI) law, helps villagers get access to critical government information that they can then use to claim their rights and benefits.

When I visit Mr Yadav, a group of people are milling around, many of them armed with papers, and visibly agitated.

He goes through stacks of documents, makes notes and gives suggestions.

It is clear that many of them are looking to Mr Yadav for solutions to their problems.

Unsung Indians

This is the ninth article in a BBC series Unsung Indians, profiling people who are working to improve the lives of others.

More from the series:

The doctor who delivers girls for free

Cancer survivor bringing joy to destitute children

A messiah for India's abandoned sick

The woman whose daughter's death led her to save others

The man saving Mumbai water one tap at a time

'Powerful weapon'

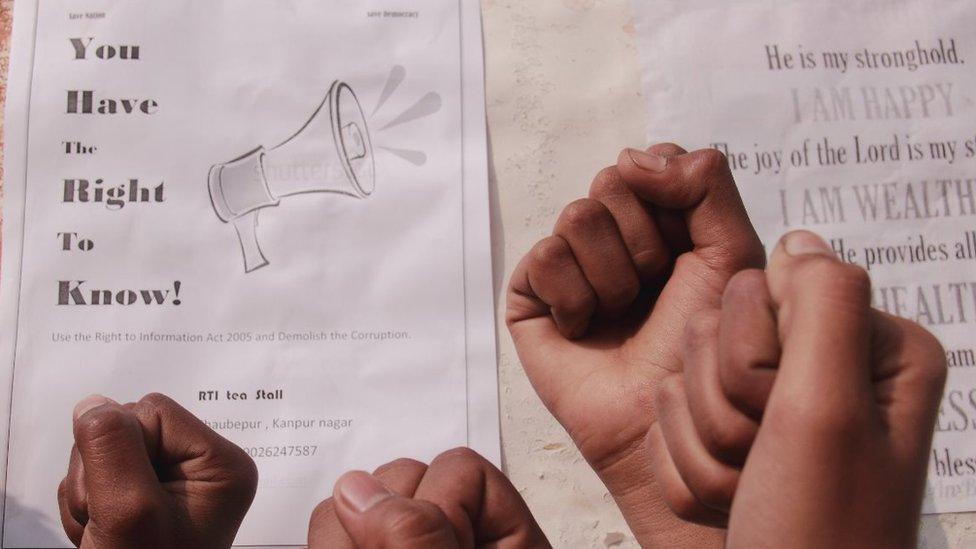

The RTI law, also called India's "weapon of the weak", has since 2005 enabled citizens to question government officials. It has been lauded for helping expose misdeeds and corruption in government departments.

But the law also has its limitations.

"People who cannot read and write in India's villages find it difficult to file applications, and even those who are literate often don't know the procedures," Mr Yadav tells the BBC.

"That's where I come into the picture. I just help them raise their voices through RTI, one application at a time."

His tea stall is the nerve centre of his activities.

Villagers regularly visit him to seek his help

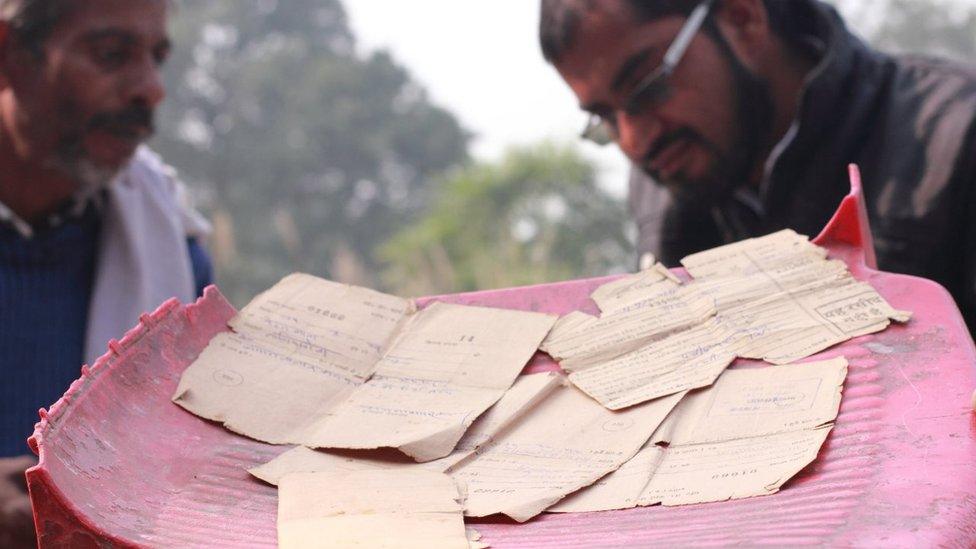

He gets government papers dating back to the 1970s

Mr Yadav spends three hours every morning at his tea shop to hear problems faced by villagers

Most applications often require Mr Yadav to go through a large number of files

Local residents of Chaubepur and its neighbouring areas refer to Mr Yadav as "the information soldier" and "a modern day Mahatma Gandhi".

But he disagrees with these labels.

"I am just an activist trying to help these villagers get crucial information about their problems," he says.

Mr Yadav started participating in RTI awareness campaigns in 2010 after leaving his job in the nearby city of Kanpur. He soon realised that it was the people in India's villages who needed the law more.

In 2013, he rented a small room in the village and started using the tea stall as his office.

He has filed more than 800 RTI applications since then.

The issues faced by the people of Chaubepur could be a template for the problems encountered by any Indian village. Land disputes, loan schemes, pensions, road construction and funds for local schools figure prominently.

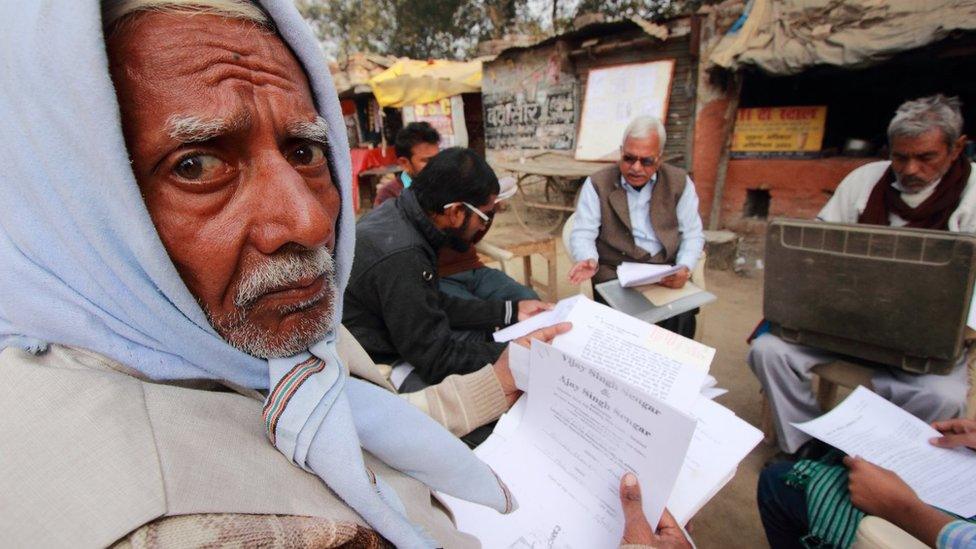

Rameshra Chandra Gupta has been fighting to get food security for people

Raj Bahadur Sachan has filed a case to get his land back

Badai Kashyap wants the government to provide an irrigation canal to his fields

Raj Bahadur Sachan says he has been trying to get his farmland back from some powerful people who he alleges have illegally occupied it.

Mr Sachan, 55, tells the BBC that a court in 1994 ordered that the land belonged to him. But more than two decades later, he is still trying to claim it.

He met Mr Yadav last year and filed RTI applications to get a copy of the court order and information from other government departments.

"His case is taking a long time because a number of government offices are involved. But at least he now has all the papers he needs to file a fresh petition," Mr Yadav says.

'He lives among us'

Ramesh Chandra Gupta, 70, has been fighting to ensure that the people in his village get cheaper grains from a government-run shop.

"The contractor at the shop was selling grains at a higher price than the government rate. I filed an RTI plea with Mr Yadav's help to get the real prices, which were at least 20% cheaper than what he was charging," he says.

"Officials were forced to take action because I had the right information."

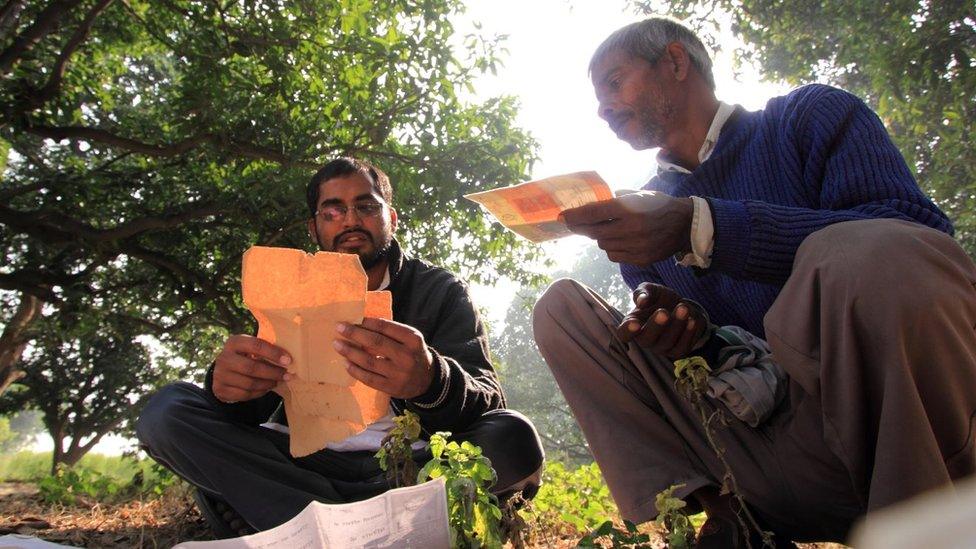

Mr Yadav regularly visits villages to create awareness about the RTI

Local youth of the village support Mr Yadav's campaigns

Mr Yadav wants to train at least one "RTI volunteer" in every village of Uttar Pradesh

Mr Yadav also files applications on his own.

"I have personally filed more than 200 applications about government funds for schools, money allocated for road construction and drinking water supply," he says.

"In most cases I was able to put pressure on government officials to get public work done because I had the right information."