Kashmiri Hindus: Driven out and insignificant

- Published

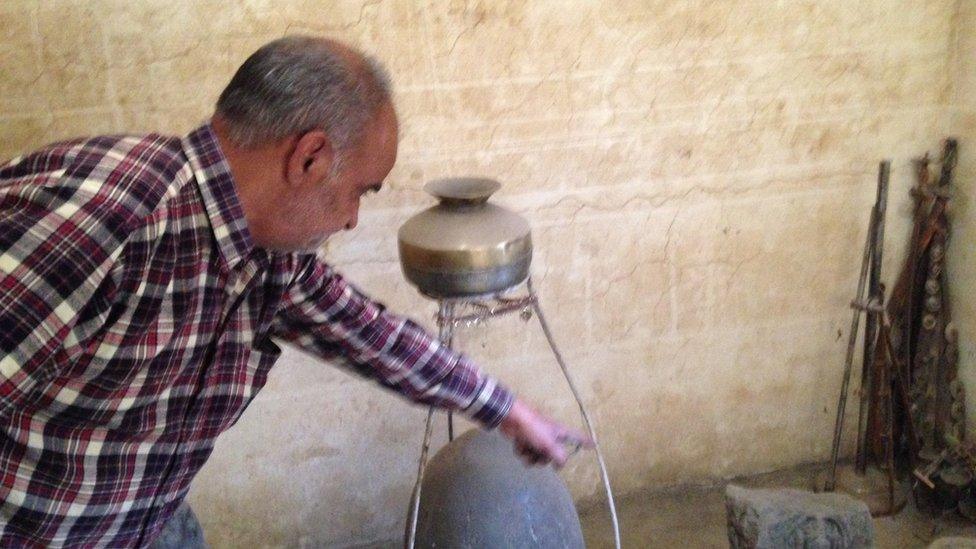

Mohan Lal Bhat is among the 3,000-5,000 Pandits left in the Muslim-dominated valley

In a room opposite an ancient temple in Srinagar, four men - two Hindu and two Muslim - are hotly debating the exodus of hundreds of thousands of Kashmiri Hindus from Indian-administered Kashmir in the early 1990s.

The two Muslims sympathise with the Hindu migrants, also known as Kashmiri Pandits, calling them victims of circumstance. They admit the Hindus were wronged, but are quick to add that they were helpless to stop the mass migration.

For the Hindu men, temple keeper Maharaj Pandita and his friend Sanjay Tikku, the "absence of the Muslim community's collective guilt" over what happened is a familiar frustration.

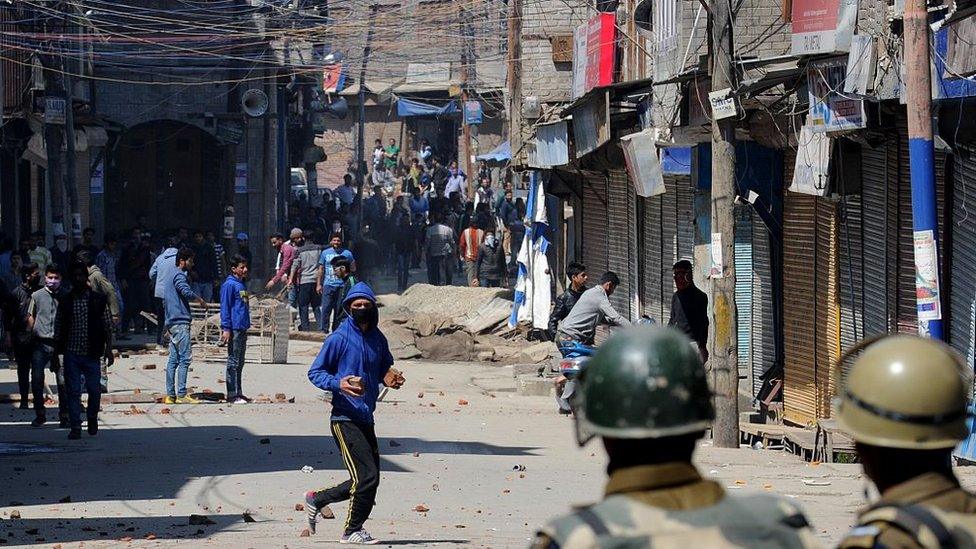

It has been 27 years since a violent armed insurgency erupted in Kashmir, completely paralysing its politics and crippling its economy.

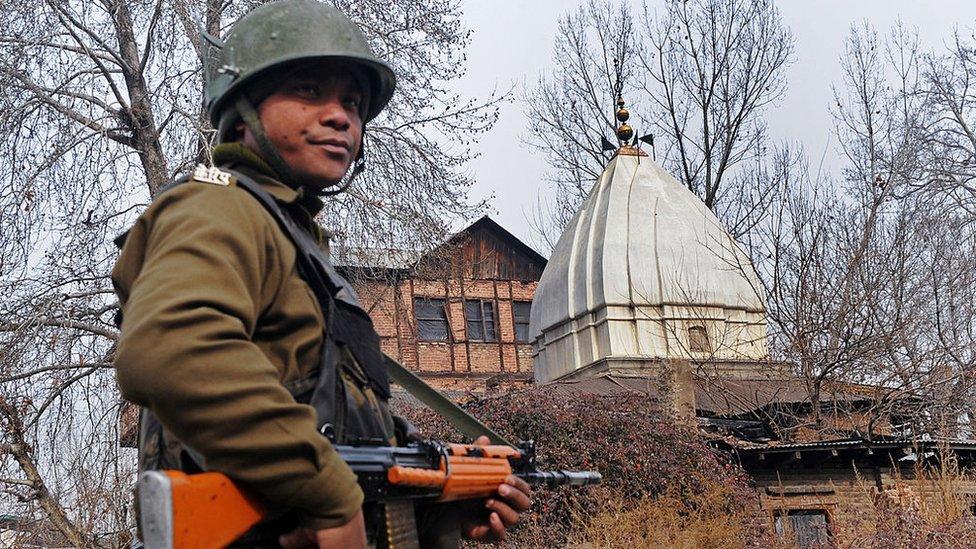

There are many Hindu temples in the valley...

...but few Hindu priests are available for religious occasions

It also tore apart the centuries-old harmony that existed between the majority Muslim and tiny but influential Hindu communities, after the latter was terrorised into leaving.

Muslim militant groups targeted Hindus by killing their men, burning their homes and damaging their places of worship. Mosques would make calls for them to leave the valley.

Saifullah, a former militant, tells the BBC that he regrets participating in driving Kashmiri Hindus out. "We want them back. We want them to live in peace. Kashmir is theirs too," he says.

Insignificant numbers

The bulk of Kashmir's Hindus are now settled in neighbouring Jammu city and the Indian capital Delhi.

Some, like Mr Pandita and Mr Tikku never left, though more out of compulsion rather than defiance.

The number of those who stayed, however, is insignificant. Finding Kashmiri Pandits in the Muslim-dominated valley is like looking for a needle in a haystack.

Today the Pandits are condemned to live a life of anonymity in their own homeland

According to one estimate, 3,000-5,000 Pandits are left in the valley today - a far cry from the 300,000 who used to live there. These few thousand are scattered over 185 places in the valley, where seven million people live.

Today the Pandits are condemned to live a life of anonymity in their own homeland.

'Painful times'

Mr Tikku and Mohan Lal Bhat, like most Hindus who did not leave Kashmir, lived nightmarish existences during the initial phase of the conflict.

"In the beginning there was a lot of fear, nights were eerily silent. If a cat jumped on to the roof we thought militants had come to kill us", Mr Tikku tells the BBC.

Mr Bhat, a retired policeman, also recalls the "painful times" he used to be up all night "in case someone came to kill us".

Kashmir has been relatively peaceful in recent years

"I would look out of the window to see if an intruder was coming to kill us," he says.

The Bhats never left the valley and poverty never left them. A young son was killed in a terror attack. The other is unemployed. Like many others in the valley, they have their own homes, but ready cash is scarce.

For the community, the scars undoubtedly run deep, but it seems that time has nearly healed their wounds. They now enjoy healthy relationships with their Muslim neighbours.

Peace problems

But relative peace comes with its own set of problems.

Many complain about a lack of priests. This becomes an issue during occasions like weddings, and also during deaths, when priests are needed to perform the last rites.

Another problem, according to Mr Tikku, is finding partners for their children.

He estimates that there are around 900 Pandit boys and girls of marriageable age in the valley. Mr Pandita himself has three daughters, none of them married yet. "We would like to get our daughters married in the valley but it's not easy to find the boys in our community," he says.

There were protests last year against a government proposal to create exclusive settlements for Kashmiri Hindus

Children's education is another worry.

Many young parents are unwilling to raise their children in a predominantly Muslim Kashmir, where all children "have to learn Arabic and the Koran".

Sonica Bhatt is 30 and has three children. The oldest is six. She says she has not told them about their Hindu background yet, because their friends are all Muslim. "We want to send them to Jammu where they will be raised as Hindus," she says.

Identity crisis

Writer Manoj Pandita, a police officer, doesn't think education is a problem for Hindu children. He says he went to a local school where he had to learn Islamic tenets.

Journalist Manohar Lalgami, who is the only Hindu employee in an Urdu newspaper, agrees.

He says he is not scared of speaking his mind to his fellow Muslim journalists. "I am loudmouthed and forthright. That has earned me my colleagues respect," he tells the BBC.

Relations between the two communities are better now

Mr Lalgami is among many internally displaced Kashmiri Hindus. He had to abandon his ancestral home and settle in Srinagar in a cluster of flats built by the federal government under a scheme that has seen more than 2,000 members of his community return to the valley.

To him, the real problem for the valley Pandits is official apathy.

"Unfortunately neither has the government paid attention to us nor has any political party raised our problems," he says.

"You can say we have been overlooked by everyone," he says.