Why are India's housewives killing themselves?

- Published

There are very few studies on why Indian homemakers have been killing themselves

More than 20,000 housewives took their lives in India in 2014.

This was the year when 5,650 farmers killed themselves in the country.

So the number of suicides by housewives was about four times those by farmers. They also comprised 47% of the total female victims.

Yet the high number of homemakers killing themselves doesn't make front page news in the way farmer suicides do, year after year.

In fact, more than 20,000 housewives have been killing themselves in India every year since 1997, the earliest year for which we have information compiled by the National Crime Records Bureau , externalbased on occupation of the victim. In 2009, the grim statistic peaked at 25,092 deaths.

Forget raw numbers.

The rate of housewives taking their lives - more than 11 per 100,000 people - has been consistently higher than India's overall suicide rate since 1997. It dropped to 9.3 in 2014, yet suicide rate for housewives was more than twice those for farmers that year.

Little attention

Suicide rates of housewives vary from state to state.

In 2011, for example, their rates - more than 20 per 100,000 people - were higher in states like Maharashtra, Pondicherry, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Goa, West Bengal and Gujarat. Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar showed lower suicide rates.

Peter Mayer, who teaches politics at the University of Adelaide and has spent much time studying the sociology of suicide in India, wonders why suicide rates of housewives in India is so high, external, and why it gets so little attention in the media.

After all, as Mr Mayer says, research in western societies suggests that "marriage confers protection from suicide to married women".

Therefore, married people are less likely to kill themselves - studies have found suicide rates for married people in the US and Australia, for example, are lower than others in the same age group.

India, clearly, is an outlier.

Nearly 70% of people who took their lives in 2001, for example, were married - 70.6% of the men and 67% of the women.

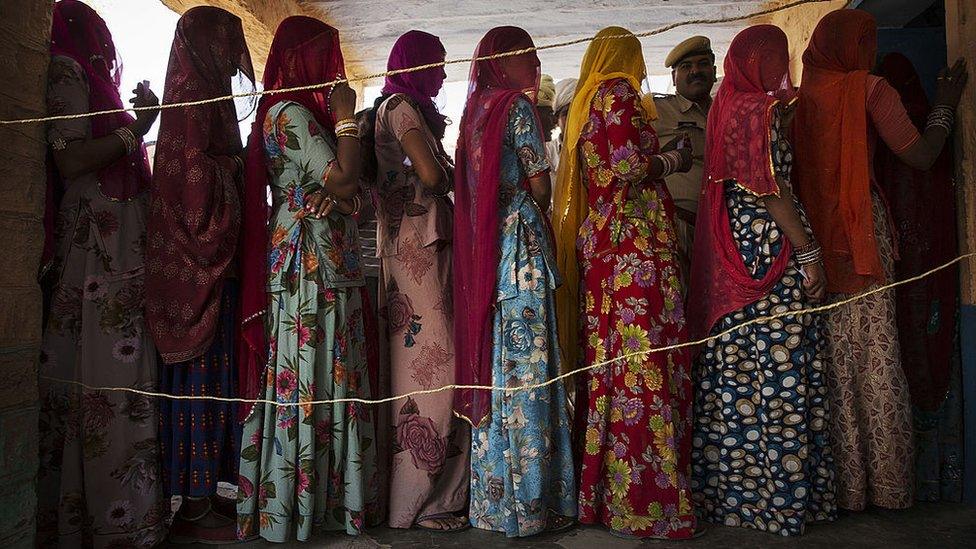

Suicides of women do not get much coverage in the media

A study , externalpublished in the medical journal The Lancet in 2012 found that the suicide rate in Indian women aged 15 years or older is more than two and a half times greater than it is in women of the same age in high-income countries, and nearly as high as in China.

Married women are part of the cohort. Mr Mayer, author of Suicide and Society in India, and co-researcher Della Steen, found that the "risk of suicide is, on the whole, highest in what are probably the first or second decades of marriage, that is, for those aged between 30 and 45".

"We found that female literacy, the level of exposure to the media and smaller family size, all perhaps indicators of female empowerment, were correlated with higher suicide rates for women in these age groups."

Also, the researchers say that suicide rates among housewives are lowest in the most "traditional" states, where family sizes are big and extended families are common. Rates are higher in states where households are closer to nuclear families - Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Kerala. (Dowry-related deaths are treated as murders.)

'Changing expectations'

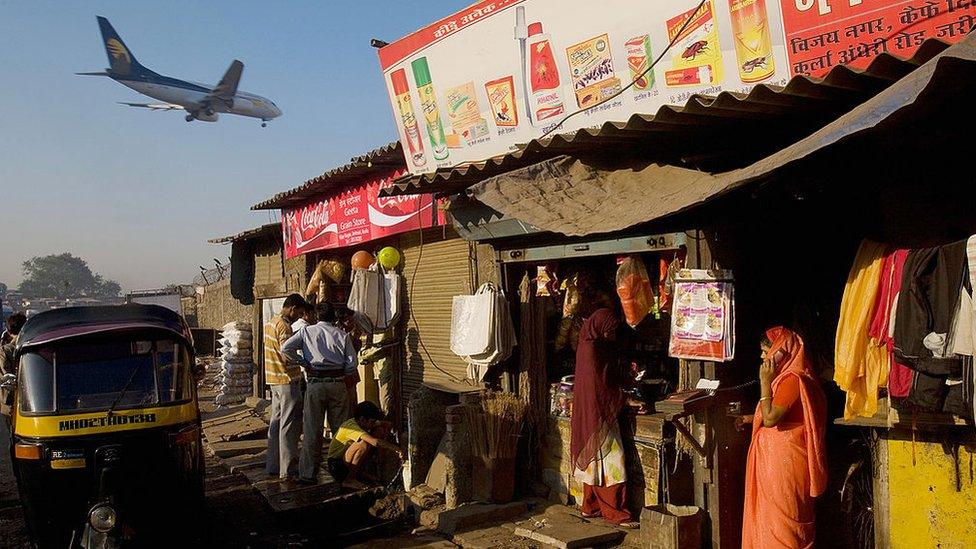

Mr Mayer told me that he believed the high rate of housewife suicides was linked to the "nature of the social transformation in the nature of the family, which is occurring in India".

"I suggest that a central explanatory factor is the importance of changing expectations concerning social roles, especially in marriage," he says.

There are conflicts with spouses and parents, and "relations between poorly educated mothers-in-law and better-educated, insubordinate daughters-in-law" are a source of tension.

An educated daughter-in-law was more likely to "forge a strong alliance with her husband and persuade him to break off from his parents and set up a nuclear family on their own", according to one study by Joanne Moller.

Dr Vikram Patel, a leading Goa-based psychiatrist and professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who co-authored the Lancet study, tells me that the high rate of housewife suicides in India can be attributed to a double whammy of "gender and discrimination".

"Many women face arranged marriages by force. They have dreams and aspirations, but they often do not get supportive spouses. Sometimes their parents don't support them either. They are trapped in a difficult system and social milieu," he says.

"The resulting lack of romantic, trusting and affectionate relationship with your spouse can lead to such tragedies."

Making things worse is the lack of counsellors and medical facilities for patients of depression. Then there's the social stigma associated with "mental illness".

Next big question: why does the media ignore the rising rate of suicides among married women, when, say, farmer suicides, rightly, gets a lot of attention?

'Harassment for dowry'

Mr Mayer says on the "relatively rare occasion when the Indian media do cover the suicides of married women it is almost always framed in terms of mistreatment by in-laws and harassment for dowry". That is clearly only a part of the story.

Kalpana Sharma, a researcher and journalist, says the lack of coverage has to largely do with the "invisibility of gender" in the Indian media.

"This, in some ways, is worse than misogyny. There is a lack of engagement with issues relating to women, and the media is not even aware of the problem," she says.

The story of India's "desperate housewives", as Mr Mayer describes them, needs to be urgently researched and told.