Viewpoint: Koh-i-Noor - a gift at the point of a bayonet

- Published

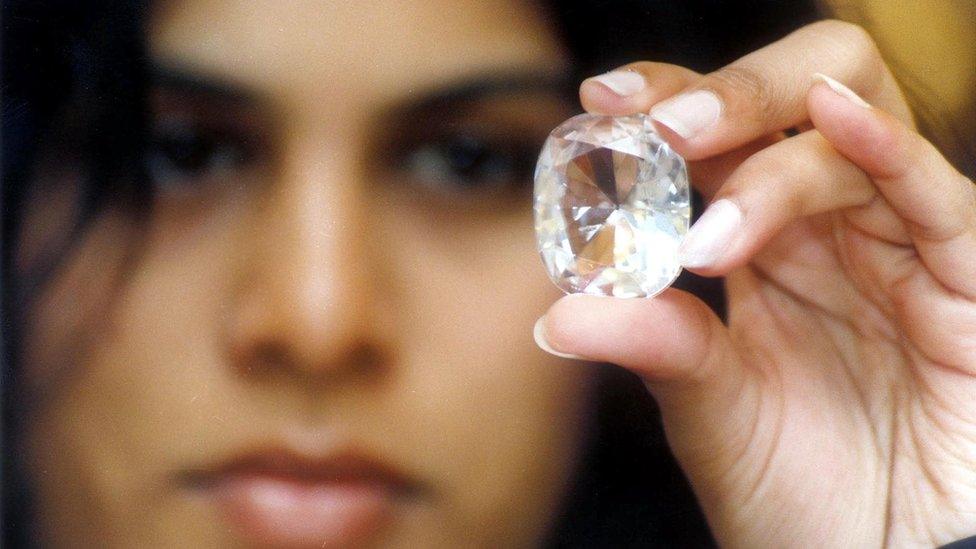

The jewel is in the crown worn by the Queen Mother, which was displayed on her coffin during her funeral

That the Koh-i-Noor diamond carries a curse is no secret. However, the fact that it can turn government policy inside out within the space of 24 hours has been news to us all.

First, the Indian solicitor-general stated that his country would not be pursuing the return of the diamond. A day later, the Narendra Modi government said it would do everything in its power to "amicably" encourage the British to give back the gem.

Solicitor-General Ranjit Kumar's argument to the Supreme Court was that the Koh-i-Noor had not been "stolen nor forcibly taken away". Rather, it had been given to Britain by the successors of Maharajah Ranjit Singh "as compensation for help in the Sikh wars".

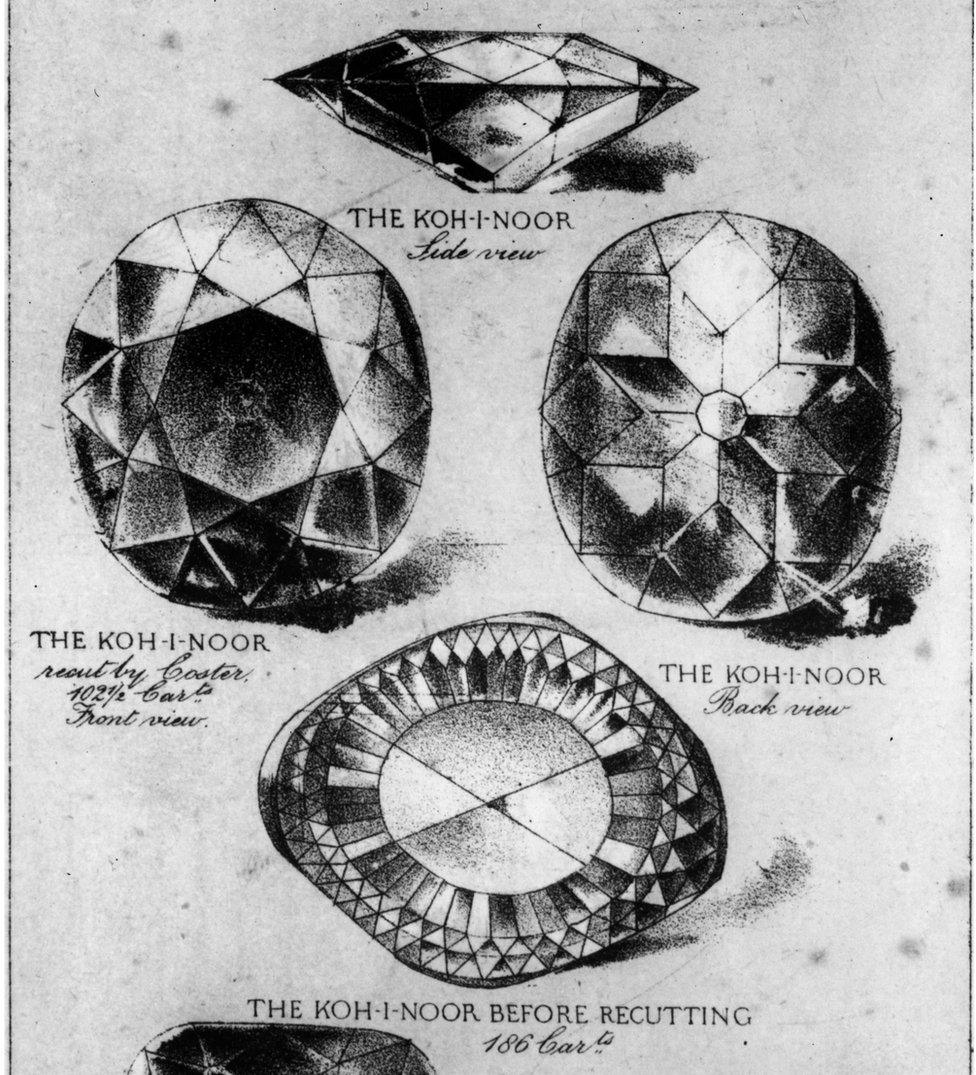

Such a bold full stop in a long-running dispute over the ownership of this fabulous 105-carat gem came as quite a shock to most Indians.

It was also wildly inaccurate. Maharajah Ranjit Singh, who once wore the uncut Koh-i-Noor on his bicep, died in 1839. Almost a decade later, the Koh-i-Noor was taken by the British, by force, from a frightened little boy, his son.

Therefore the diamond came to Britain thanks to dubious legality and very clear immorality.

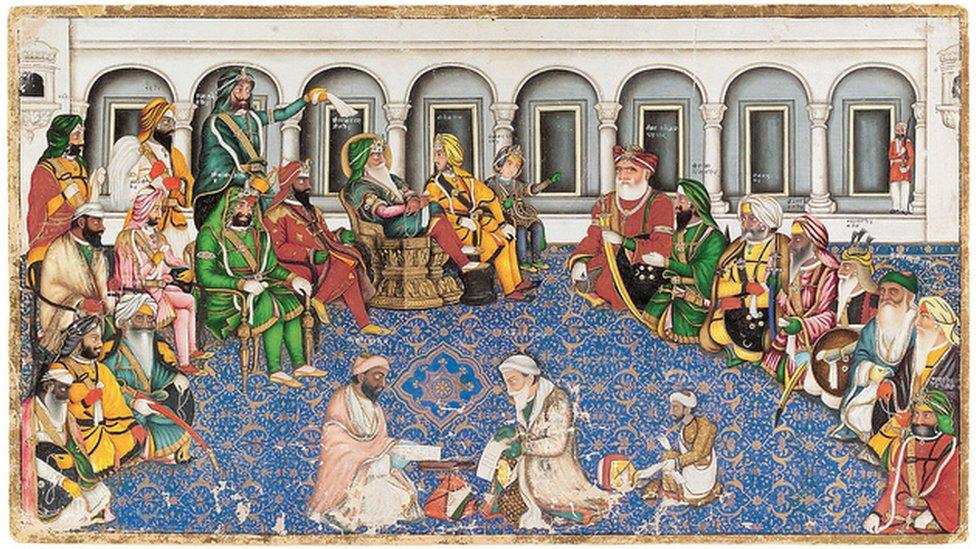

Ranjit Singh founded the Sikh kingdom of the Punjab

The boy King, Duleep Singh, son of Ranjit Singh, was only 10 when he signed over his Kingdom and Koh-i-Noor in 1849, although arguably all was lost three years before, when the British were invited into the Citadel. Why were they allowed into a foreign realm in this manner?

Despite signing treaties of friendship with Ranjit Singh, after his death the British began garrisoning troops around the border.

These were deemed acts of naked aggression by the Sikhs and provoked war. Having surreptitiously cut deals with leading members of his court, the British managed to persuade them to betray their King and weaken his army, leading to defeat in the first Anglo-Sikh War.

Still faced with a formidable force in the Sikh Kingdom, the British insisted that they wished to leave the Maharajah on the throne, thus taming any potential "native" uprising. There were stringent conditions however. The British were to be given "full authority to direct and control all matters in every Department of the State."

Inveigling their way into the Lahore Durbar in this way, they separated Duleep Singh from his mother, the Regent, dragging her screaming to a tower and contrived a second Anglo-Sikh war. What was left was a thoroughly weakened realm.

Alone and terrified, this small child was surrounded by grown British men, and told to sign away his future.

Later in life Duleep Singh would attempt to take legal action against the British over their conduct. But living in exile in England by this time, he was thwarted at every turn and eventually died a broke and broken man.

Drawings of the Koh-i-Noor diamond dating back to circa 1860

There have been previous attempts to get the diamond back but they have all stalled. I suspect none of the previous petitioners really expected to get the gem out of the Tower of London.

India is not the only nation in the game.

Earlier this year a British-trained barrister, Javed Iqbal Jaffry, successfully lodged a petition with a Pakistani court.

In Mr Jaffry's words: "Grabbing and snatching [the Koh-i-Noor] was a private, illegal act which is justified by no law or ethics".

Though the Indians want the stone in Delhi, he insists its true home is Lahore, the former capital of Duleep Singh's empire.

I am currently writing a history of the Koh-i-Noor with the splendid historian William Dalrymple, and we have both been up to our elbows in various dusty archives both here and in India.

Had the diamond truly been a gift, the Delhi Gazette, a British newspaper, would hardly have printed in May 1848: "This famous diamond (the largest and most precious in the world) forfeited by the treachery of the sovereign at Lahore, and now under the security of British bayonets at the fortress of Goindghur, it is hoped ere long, as one of the splendid trophies of our military valour, be brought to England in attention of the glory of our arms in India".

I don't know about you, but I don't know of many "gifts" that are handed over at the point of a bayonet.

Correction 21 April 2016: This story has been amended to clarify that Duleep Singh signed over the jewel in 1849 and not 1847.

- Published20 April 2016

- Published4 December 2015