Why are many Indian Muslims seen as untouchable?

- Published

Untouchability among Muslims is rarely discussed

Untouchability is worse than slavery, said Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar, one of India's greatest statesmen and the undisputed leader of the country's Dalits.

Dalits (formerly known as untouchables) are some of the republic's most wretched citizens because of an unforgiving Hindu caste hierarchy that condemns them to the bottom of the heap.

Although untouchability among Hindus is widely documented and debated, its existence among India's Muslims is rarely discussed.

One reason possibly is that Islam does not recognise caste, and promotes equality and egalitarianism.

Most of India's 140 million Muslims are descended from local converts. Many of them converted to Islam to escape Hindu upper-caste oppression.

'Lived reality'

Their descendants form the overwhelming majority - 75% - of the present Indian Muslim population, and they are called the Dalit Muslims, external, according to Ejaz Ali, leader of an organisation representing socially disadvantaged Muslims.

"But caste and untouchability is a lived reality for Muslims living in India and South Asia," Dr Aftab Alam, a political scientist who has worked on the subject, told me. "And untouchability is the community's worst-kept secret."

Studies have claimed that "concepts of purity and impurity; clean and unclean castes" do exist among Muslims groups.

Most of India's 140 million Muslims are descended from local converts

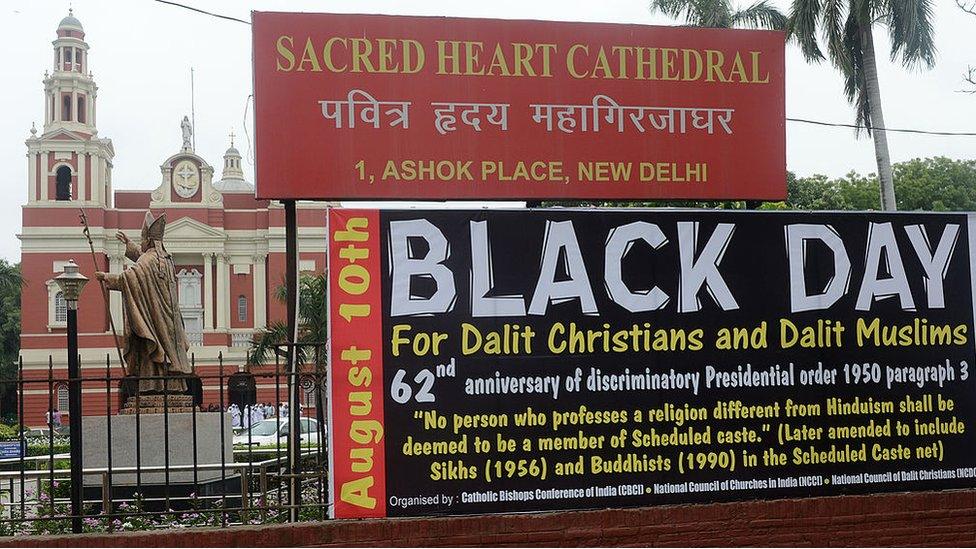

Many believe that Dalit Muslims - and Christians - deserve affirmative action benefits like their Hindu counterparts

A book by Ali Anwar says while Dalits are called asprishya (untouchable) in Hindu society, they are called arzal (inferior) among the Muslims. A 2009 study by Dr Alam found there was not a single "Dalit Muslim" in any of the prominent Muslim organisations, which were dominated essentially by four "upper-caste" Muslim groups.

Now a major study, external - possibly the first its kind - by a group of researchers reveals that the scourge of untouchability is alive and well among Indian Muslims.

Prashant K Trivedi, Srinivas Goli, Fahimuddin and Surinder Kumar polled more than 7,000 households across 14 districts between October 2014 and April 2015 in the populous northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.

'Food from different plates'

Some of their findings include:

A substantial proportion of the "Dalit Muslims" report that they do not receive an invitation from non-Dalits for wedding feasts, possibly because of a history of social segregation.

A section of "Dalit Muslims" testify that they are seated separately in non-Dalit Muslim feasts. Almost a similar proportion of respondents confirm that they eat after the upper-caste people have finished. Many say they are served food on different plates.

Around 8% of "Dalit Muslim" respondents report that their children are seated in separate rows in classes and also during school lunches.

At least a third of them state that they are not allowed to bury their dead in an "upper-caste" burial ground. They do so either in some other place or in one corner of the main ground.

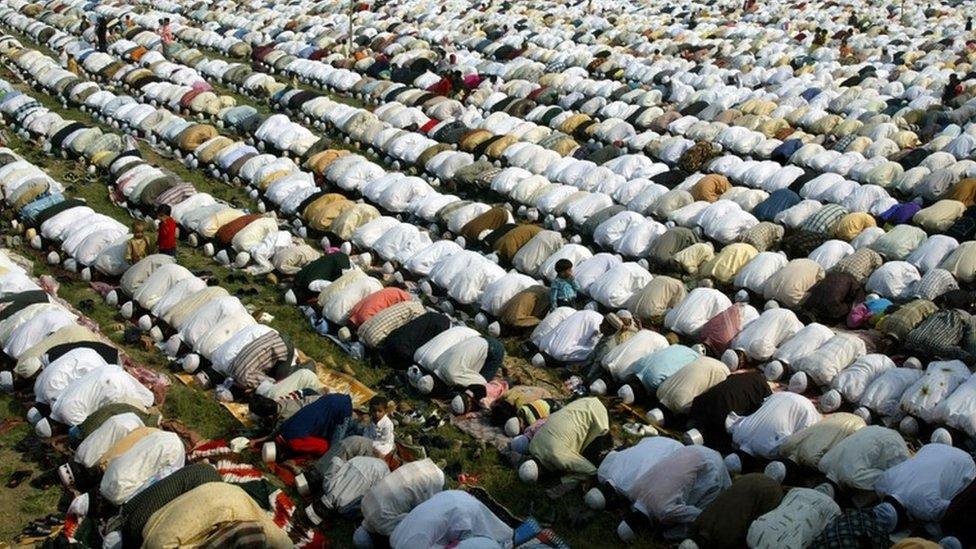

Most of the Muslims offer prayers in the same mosque, but in some places "Dalit Muslims" felt discriminated against in the main mosque.

A significant section of "Dalit Muslims" also feel that their community is seen as being associated with menial jobs.

When "Dalit Muslim" respondents were requested to share their experiences inside homes of upper-caste Hindus and Muslims, around 13% of them reported having received food/water in different utensils in "upper-caste" Muslim houses. This proportion is close to 46% in the case of upper-caste Hindu homes.

Similarly, around a fifth of respondents felt that upper-caste Muslims maintained a distance from them, and a quarter of "Dalit Muslims" went through similar experiences with upper-caste Hindus.

Caste-related prejudices are found among all religious communities - including Sikhs - in India. Parsis are possibly an exception.

"But a belief that caste is a Hindu phenomenon since caste system derives legitimacy from Hindu religious texts, has dominated thinking of governments and academia since the colonial period," says Prashant K Trivedi.

So he and his co-researchers believe that "Dalit Muslims" - and Christians - deserve affirmative action benefits like their Hindu outcaste counterparts.

The moral of the story: you can try to leave caste in India, but caste refuses to leave you.