Viewpoint: Why blood transfusions are still giving Indians HIV

- Published

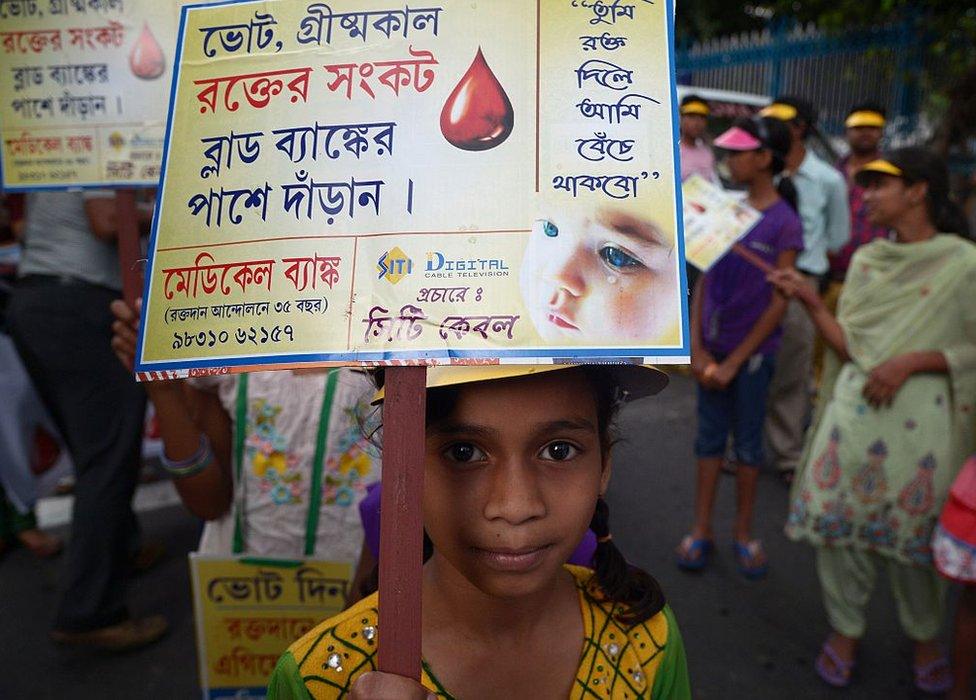

India's blood safety has been weak and needs to be reviewed

A recent news report on HIV transmission through blood transfusion in India has been the cause of much controversy.

According to information revealed by the country's National Aids Control Organisation (Naco) in response to a petition filed by an information activist, 2,234 Indians have contracted HIV while receiving blood transfusions in hospitals in the past 17 months alone.

Despite wide scale efforts, blood transfusions remain a source of HIV infections not just in India but globally. The percentage, however, varies considerably between high-income and low-income countries.

India's own rate of HIV transmission from blood transfusion has come down considerably and now stands below 1%.

Yet, while in terms of percentage this may seem small, the large number of cases - India has around 2.09 million people living with HIV/Aids - means that the absolute number is considerable.

Poor safety

So 2,234 cases in 17 months cannot be dismissed as miniscule. These are lives that have been put at enormous risk and trauma.

The daily fight of those infected and their families goes unrepresented in this play of numbers. We forget they have to live with this debilitating and stigmatised disease for life despite displaying no high-risk behaviour on their part.

The figures also point to crucial aspects that must be considered - India's blood safety standards are poorly implemented and its fight against HIV is slackening.

We, however, should first consider these basic facts.

India is annually short of over several million blood units. Thus, blood is rare and often a life-saving substance for many.

India needs to promote blood donations from regular, voluntary, unpaid low-risk blood donors

A considerable number of those who donate blood are poor and do so for money.

Even though India has banned blood banks from paying donors, the sale of blood continues to be lucrative in the black market.

Otherwise, there are replacement donors - where families are asked by hospitals to get donors to replenish their stock for a patient in need of blood transfusion. This is also technically illegal but considered acceptable.

While the government sets standards for blood safety, these are often poorly implemented and lapses are common.

Screening donors

While all donors should be tested for HIV, hepatitis, and syphilis, government empanelled blood banks clearly do not always follow procedure. As a result, blood transfusions still result in thousands of new HIV infections.

There is also the question of the 'window' period where a donor infected with HIV does not test positive for weeks.

There are tests that can reduce this window period to seven days but these are expensive and not used by every state.

Ideally, potential donors should be screened, their medical histories examined and they should be counselled even before they donate blood, to make sure they don't carry any infections.

The blood should then be retested by banks. Given the considerable demand however, this almost never happens.

And ironically, even though India has inadequate supplies of blood, it is often transfused unnecessarily.

This not only needlessly exposes patients to the risk of HIV, hepatitis and other serious side effects, but also reduces the availability of blood for patients for whom transfusion is essential.

A considerable number of those who donate blood are poor and do so for money

We must recognise the two key issues at play here.

First, India's blood safety standard has always been weak and needs to be reviewed, and implemented stringently.

Second, India's fight against HIV has slowed due to reduced funding, external and growing complacency. Not surprisingly, these issues are interlinked.

Where blood safety is concerned, India needs to promote blood donations from regular, voluntary unpaid low-risk blood donors with a careful assessment of their suitability to donate.

There needs to be stringent implementation of the screening of all donated blood in accordance with quality requirements for, at minimum, HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and syphilis.

Unnecessary transfusions must be discouraged, as patients have little or no agency to question blood safety.

Neglect and apathy

India must also renew its fight against HIV.

As the number of new infections has fallen, funding has been cut and prevention programs on the ground have suffered.

Also, over the last two years, the HIV/Aids program has witnessed wide scale stock deficiencies of essential drugs and testing kits due to bureaucratic delays with little or no accountability.

Officials wait until a crisis blows to react and then go back to status quo. This is not acceptable.

India needs to increase, not decrease, it's funding for health.

India has around 2.09 million people living with HIV/Aids

Instead of 100 smart cities, external India needs 100 health cities where the public health system is not overburdened and decaying, and patients can access care at reasonable or no cost without fear of infection.

All of this is critically hinged on coordination, sufficient personnel, suitable infrastructure and proper organisation.

Clearly, none of this is possible without funding and hence political and bureaucratic will - which seems perennially absent.

As the dust settles on this controversy, things will go back to the way they were.

New infections will continue to happen due to neglect, apathy or poor prevention efforts. For now, we should, consider this: 2234 people are infected with HIV because they were sick enough to need blood.

Chapal Mehra is an independent writer and public health specialist

- Published18 November 2015

- Published30 September 2015