Pariah to friend: Narendra Modi and the US come full circle

- Published

Why does Narendra Modi's Capitol address matter?

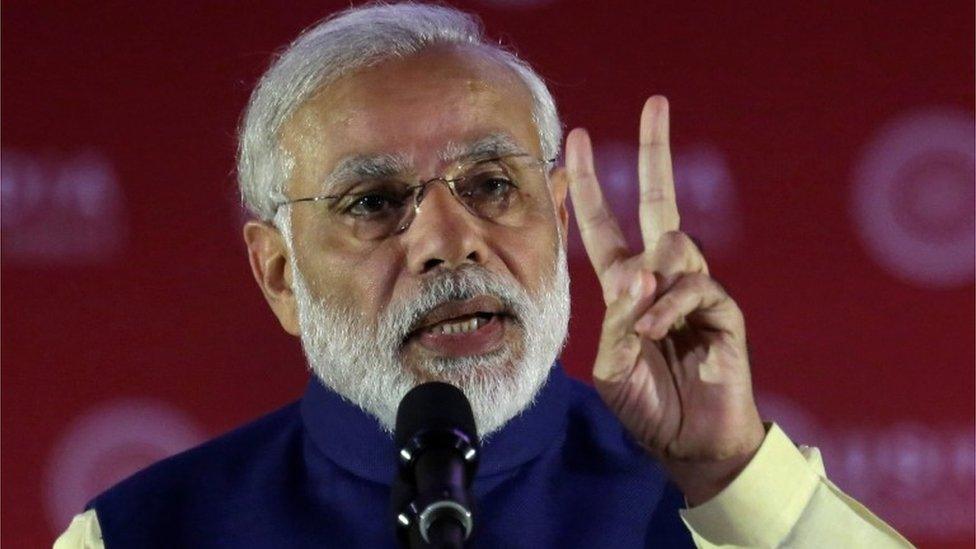

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is on a three-day visit to the US. His address to the US Congress on Wednesday will further improve his ties with US politicians and diplomats, writes Seema Sirohi.

An invitation to address a joint meeting of the US Congress is a rare honour for foreign leaders but in Mr Modi's case, it also completes the circle of rehabilitation.

When Mr Modi enters the House of Representatives on Wednesday, he will no longer be the pariah who was once blacklisted in the United States for his perceived failure to control anti-Muslim violence when he was the chief minister of the western state of Gujarat during religious riots in 2002.

The US Congress invoked a little-used section of the immigration law in 2005 to bar Mr Modi from entering the United States. As a result, President George Bush's administration revoked his existing tourist visa and denied his request for a new one to address a gathering of Indian-Americans.

Mr Modi is going to address a joint meeting of the US Congress

What's on the agenda?

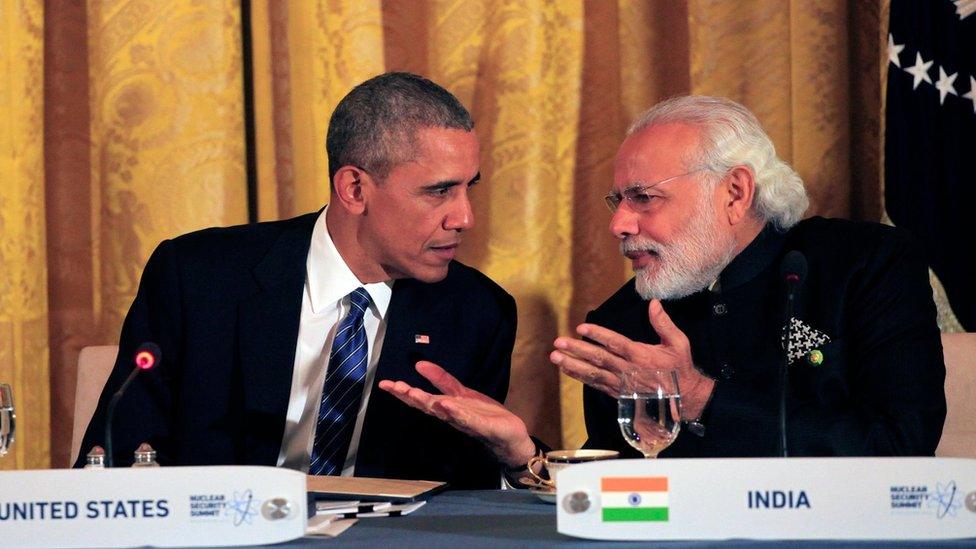

Mr Modi is meeting Mr Obama for the seventh time since he became prime minister in May 2014, highlighting the two countries' deepening strategic and financial ties. The two leaders are likely to talk about ways to further boost trade between their countries. They will also discuss India's bid for a place in the Nuclear Suppliers Group. Washington's support for this bid matters for Delhi because China has been reluctant to accept India as a member.

Military ties, defence procurement and co-operation on civil nuclear energy are also likely to be on the agenda.

And the two men are likely to explore ways to improve the US and India's strategic co-operation in the Asia Pacific region, where China is increasingly assertive.

Climate change could also figure in the talks.

The State Department cited Section 212 of the Immigration and Nationality Act, which says that any foreign government official who "was responsible for or directly carried out, at any time, particularly severe violations of religious freedom" is ineligible to enter the US.

But Mr Modi's massive victory in the 2014 national elections changed the dynamic overnight.

President Barack Obama personally called to congratulate him, quickly pivoting to recognise that Washington could not ignore the prime minister of India, the world's largest democracy, as it could the chief minister of one of its states.

Mr Modi often says that Mr Obama is his close friend

Americans are, if anything, most pragmatic in matters of state. The White House invited Mr Modi soon after and he made his first official visit as PM to the US in September 2014. Mr Obama personally accompanied him to the memorial for Martin Luther King Jr. The optics of the visit were carefully designed by the Indian side to show the US' acceptance of Mr Modi.

'Ignominy to ceremony'

But an address to the US Congress - the big prize - eluded Mr Modi for various reasons, including a potential government shut down. But more than 40 American Congressmen, senators and governors, nonetheless, attended his rally at Madison Square Garden, standing in a semi-circle to welcome him on stage. The choreography was not lost on anyone, including US diplomats in attendance.

In two years, Mr Modi has gone from ignominy to ceremony as India and the United States tried to forge an ever-closer partnership. The US Congress recognises India's importance as it does the financial and political muscle of 3.2 million Indian Americans, many of whom are supporters of Mr Modi.

But this does not mean that all senators and congressmen have forgotten the past. Nor can they ignore reports over the last two years that increasingly portray a climate of religious intolerance and communal tensions in India. Some of them may even raise questions about these issues when they meet him on Wednesday.

To drive home the point, the bipartisan Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission of the House of Representatives has organised a hearing on the human rights situation in India precisely during Mr Modi's three-day visit.

Mr Obama was the chief guest at India's Republic Day celebrations last year

Two weeks ago, during a hearing of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, many senators expressed concerns about India's record in fighting human trafficking, and child and bonded labour. They also raised questions about violent attacks on Muslims, Dalits (formerly untouchables) and Christians.

Interestingly, Mr Modi is the first and probably the last foreign leader to address a joint meeting of the Congress this year. The last speaker was Pope Francis in September.

Mr Modi is also the first Indian prime minister to be hosted for lunch in the Capitol by Speaker of the House, Paul Ryan, a Congressman who many see as a future presidential candidate. He will then move to a high-powered reception organised by the chairmen of the foreign affairs committees of both the House and Senate.

The lavish welcome on Capitol Hill is designed to heal any wounds that might have festered from the snub of 2005. Since becoming prime minister, Mr Modi has never publicly spoken about the visa denial. When asked, he said that relations between countries transcend individuals.

Indeed, for in the end it is India that is in the American calculations.