Beef or mutton? Mystery over India lynching lab results

- Published

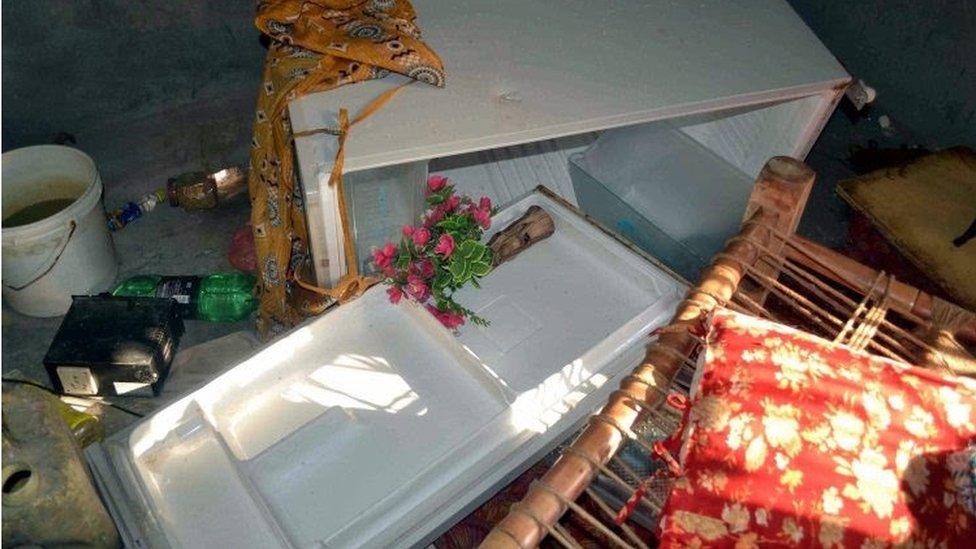

Initial reports that mutton was found in Mr Akhlaq's refrigerator are now being disputed

Last year, a Muslim man in northern India was killed in a mob lynching over allegations that his family had been storing and consuming beef at home. The case sparked widespread outrage and a furious debate about religious tolerance. Now, there's a fresh twist in the case that has raised questions over the investigation - and highlighted tensions over beef in India.

Mohammed Akhlaq was beaten to a death in the district of Dadri in September over rumours he had consumed beef.

Hindus consider cows to be sacred, and for many, eating beef is taboo. The slaughter of cows is also banned in many Indian states.

A lab test cited widely in the aftermath of the killing said the meat allegedly found in his refrigerator was mutton and not beef.

However a new lab report, revealed by the lawyers of 18 people on trial for his murder, said that the meat in question was in fact beef.

Later, it was also revealed that the meat was never in his house, but found inside a bin near his home.

Mohammad Akhlaq was a farm worker

Although police are adamant that the type of meat is irrelevant to the case, the defence team is using the new test results to demand the release of the 18 suspects, on the grounds that they were "provoked" into attacking Mr Akhlaq.

The court will hear a petition on Monday demanding that charges of cow slaughter are brought against Mr Akhlaq's family.

Why was there a discrepancy between the two lab tests, and why it has taken so long for a second report to come out?

Where was the meat found?

Soon after the incident many media reports had claimed that police had taken meat samples from Mr Akhlaq's fridge.

But police told the BBC that they had never collected meat samples from his home.

Now, eight months later, the investigating police officer, Anurag Singh, has clarified that the meat samples were collected from the place of the mob attack, about 100 metres (330ft) away from Mr Akhlaq's house.

"The body of Akhlaq was lying near a transformer near his house and that is where we found some meat and took samples of it," he told the BBC.

Why was a second test carried out?

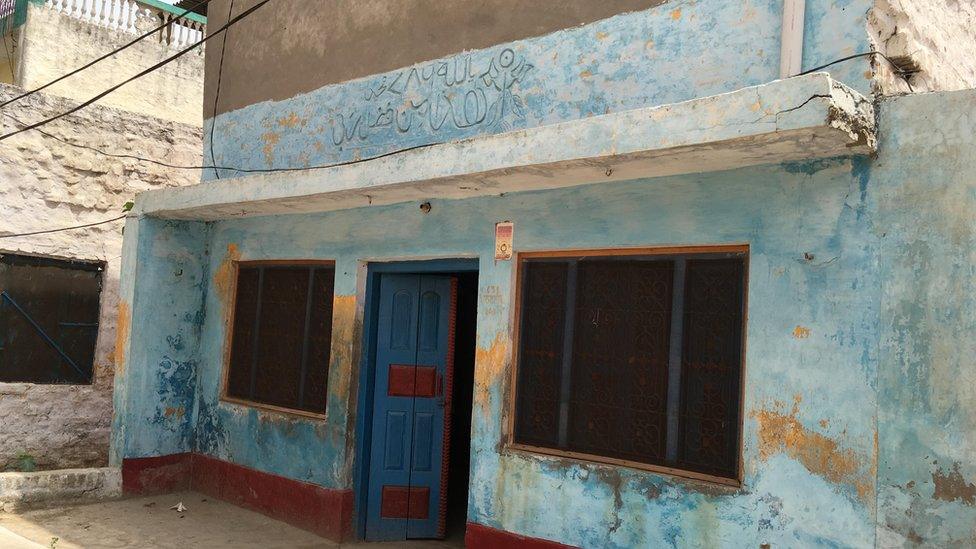

Mohammed Akhlaq's house lies abandoned

The first report, released soon after Mr Akhlaq's death, said the meat in question was mutton and was widely reported in India media.

However, Mr HC Singh, in-charge of the Mathura forensic investigation laboratory which released the second report, told BBC News that the preliminary test was only based on a "physical examination" of the meat samples.

The examination was carried out by a veterinary physician, but even he had recommended that it be sent to a lab for further conclusive testing, he added.

"Ours is the only laboratory that is equipped to do such analysis," Mr Singh said.

Why did the results of the second test take so long?

According to Mr Singh, his laboratory had known that the meat was beef as early as October.

However the test results were only submitted to the police in December.

Mr Singh attributed the delay to a "lack of postage stamps" at the laboratory and the fact that they did not have a chairman for three months - excuses that have not convinced many people.

Correspondents say the delay has led many to speculate that the laboratory was pressured into not revealing the test results, given the tensions brought about as a result of the incident.

The lab report was only revealed to the public in June after lawyers for the 18 people accused of Mr Akhlaq's murder asked the court for a copy.

Tensions high in Dadri: Vineet Khare, BBC Hindi

The entrance to the village of Bashara in Dadri

Tensions in Bashara village, where Mr Akhlaq lived with his family before he was murdered, are high.

The latest lab report has spurred relatives of the arrested men to petition the court, demanding that a case of cow slaughter be filed against his family.

The few hundred Muslims who still live in the village say they live in fear.

Reports of cow vigilante groups attacking people ferrying cattle, Hindu extremists holding arms training sessions, and reports of private Hindu armed groups operating in the region have heightened their fears. Some talk of leaving the village for good.

Prem Singh was Mr Akhlaq's neighbour and both families got along well, celebrating festivals together and attending one another's weddings.

But now he is listed as an eyewitness to Mr Akhlaq "killing a cow" and two of his grandsons are among the 18 men arrested.

His wife is angry at the arrests, and told me: "Would a Muslim tolerate it if we kill a pig and throw it outside their house?"

Will this have a bearing on the murder trial?

The court and police have consistently insisted that the new lab results will have no bearing on the case.

The police investigating the case told the BBC that "this has nothing to do with the investigation of the murder of Akhlaq by a mob."

And Ram Sharan Yadav, one of the lawyers for the accused, said that the court had turned down their request for a copy of the second lab result.

The lawyer for Mr Akhlaq's family said that "in any case there is no law in the country that says a man can be murdered because he slaughtered a prohibited animal".

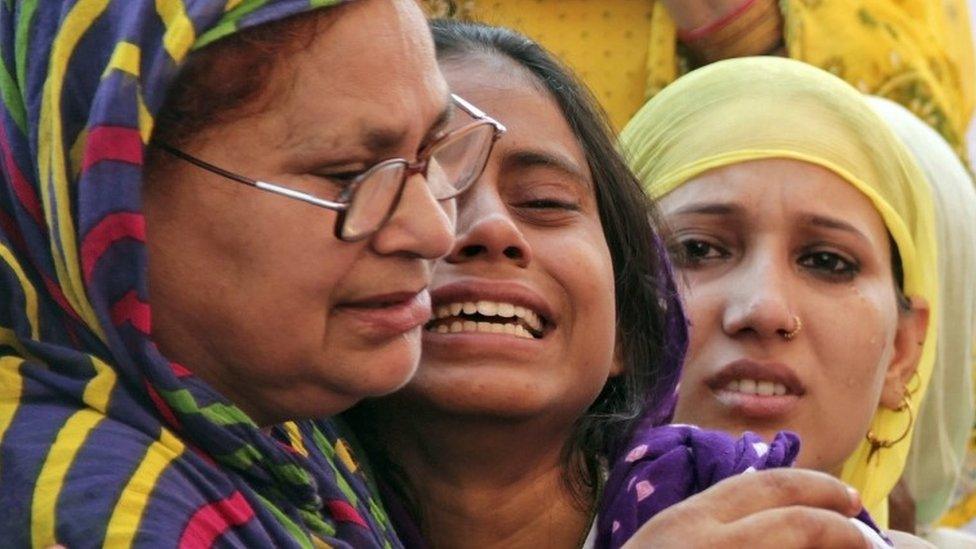

Relatives mourn after the death of Mohammad Akhlaq in the village

Uttar Pradesh is one of the 10 Indian states where the slaughter of cow, calf, bull and bullock is completely banned.

However the slaughter of buffaloes and the sale and consumption of its beef is permitted.

The defence lawyers are insisting that the mob was "provoked" and want all charges against them dismissed.

It is unclear if this will work as a line of defence - police stand firm on the fact that the two things are unrelated, and the courts have also indicated that this is not a factor that they will take into consideration.