Why Kashmir's gun factories are shutting down

- Published

Subhana and Sons began making guns in 1942

Indian-administered Kashmir used to be a thriving hub for factories that made guns for civilians. But as owning a gun has become increasingly difficult in the Muslim-dominated Kashmir Valley, the industry has been in a steady decline in recent years, writes the BBC's Geeta Pandey in Srinagar.

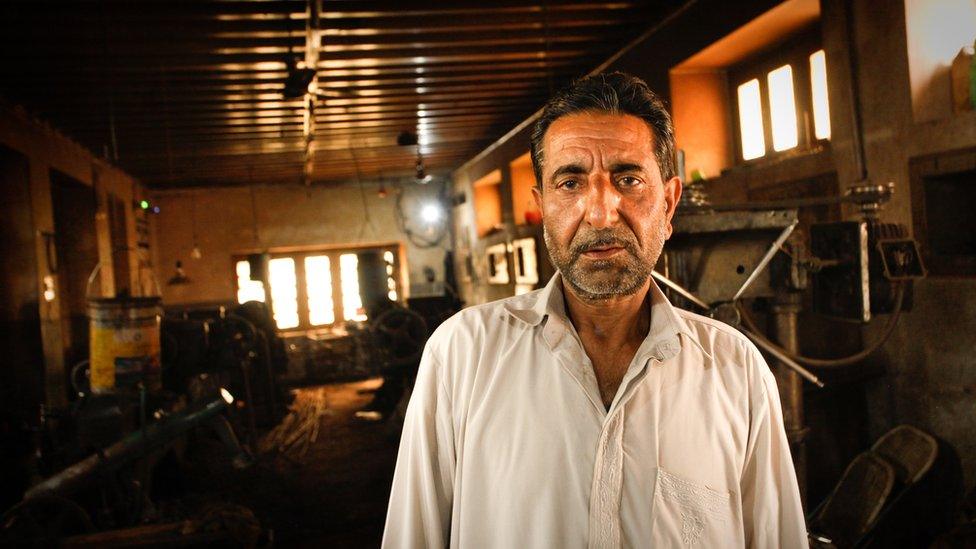

It's mid-morning on a weekday, but the Zaroo Gun Factory in the city's Rainawari area wears a deserted look.

The machines are covered in dust, tools are lying unused and a couple of men sit around, waiting.

Until 2012, the factory produced 540 single-barrel and double-barrel shotguns every year and each one of them was sold, says Nazir Ahmad Zaroo, one of the three owners of the factory.

"But in 2013, we could sell only 29 guns. In the last three years, we have not been able to sell a single gun," he says bitterly.

The rifle butt is made of walnut wood

The factories employ a handful of people now

The guns were prized for their long butts made of walnut wood and many had leaves of Kashmir's famed Chinar trees carved on them.

Their customers included buyers from within the valley, who bought guns for hunting or self-defence, and dealers from other states, including Delhi, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh.

Today, an occasional old customer walks in, looking to get an old gun repaired.

Mr Zaroo's family has been in the business since the "Mughal era" - he says his grandfather came to Kashmir from Pakistan before India's independence in 1947 at the invitation of the former ruler, Maharaja Hari Singh, for whom he made muzzle-loading guns.

The present factory was set up in 1953 by Ghulam Ahmad Zaroo, Mr Zaroo's father.

Zaroo Gun Factory was bustling until a few years ago

Nazir Ahmad Zaroo says his family has been in the business of gun making since the "Mughal era"

"In its heyday, we employed about two dozen people, many of them were local, but some came from faraway places," says manager Mohammad Shafi.

"The factory was bustling with activity. "If you'd visited us then, we would have paid you no attention, but today we have all the time in the world."

The Zaroo Gun Factory is among the only two manufacturing units that remain in the valley today - the other being Subhana and Sons.

Before 1947, there were at least a dozen factories which employed hundreds of people. Over the years, most have shut down or shifted base to the state's Jammu region.

And with that, all the market has shifted to Jammu too.

"There are more than 30 gun factories in Jammu and their quotas have been increased massively," Subhana and Sons owner Zahoor Ahmed Ahangar told the BBC.

"There are also hundreds of arms-dealers there, so buyers from other states of India no longer come to us, they all go to Jammu. We haven't sold any guns in the last two years."

The factories produce single-barrel and double-barrel shotguns used mostly for hunting

Today, they receive only a few repair jobs

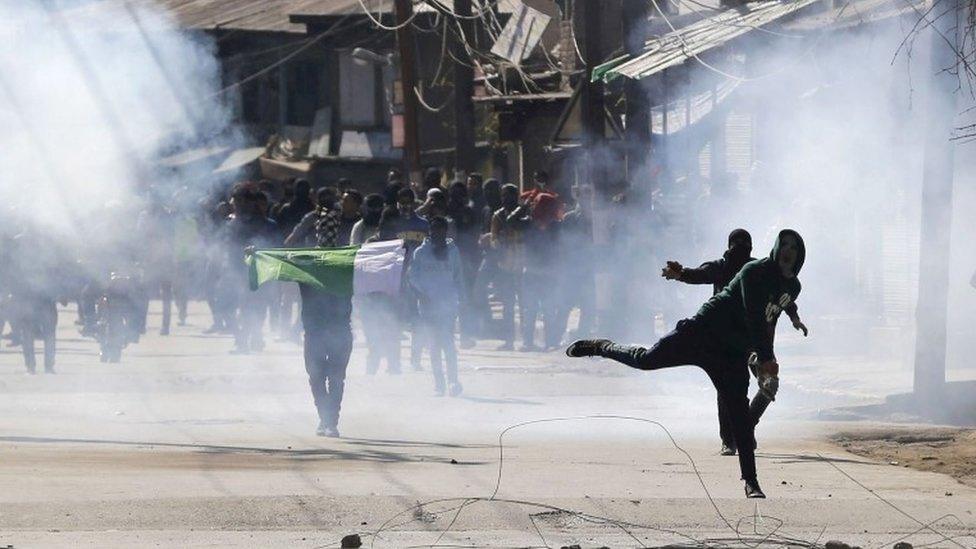

Kashmir's gun industry was banned for two years from 1989-91 when a violent insurgency began against Indian rule in the region.

The ban was lifted in 1992, but traders say the number of guns they were allowed to produce was curtailed - Subhana saw its quota reduced to 300 guns from the earlier 700.

Established in 1925, the factory initially made hunting arrows, swords and daggers. In 1942, it got a licence to make 12-bore shotguns and began manufacturing them.

Now, unable to find any buyers, the factory-owners are contemplating shutting down.

Subhana and Sons owner Zahoor Ahmed Ahangar says all their clientele has shifted to Jammu

Burhan Zaroo says militants have never been interested in "our obsolete guns"

Mr Zaroo and Mr Ahangar say the authorities have not given any reason for why they are no longer issuing licences to local people.

But, they feel that years of militancy and an unstable security environment in the region could be a reason behind the government's reluctance.

Burhan Zaroo, son of Nazir Ahmad Zaroo, says that, in 2013, they petitioned the state's home ministry to save the industry, and were assured of help, but nothing came of it.

"The fears of the security establishment are unfounded," he says. "Even at the peak of insurgency, the militants never bothered us. They are not interested in our obsolete guns. They have much more sophisticated weapons."

Adds Mr Ahangar: "The authorities must start issuing licences to eligible people after verification, otherwise this industry will die. And that will be a shame."

- Published15 June 2016

- Published1 March 2016

- Published8 August 2012

- Published1 August 2012