Jallikattu: Why India bullfighting ban 'threatens native breeds'

- Published

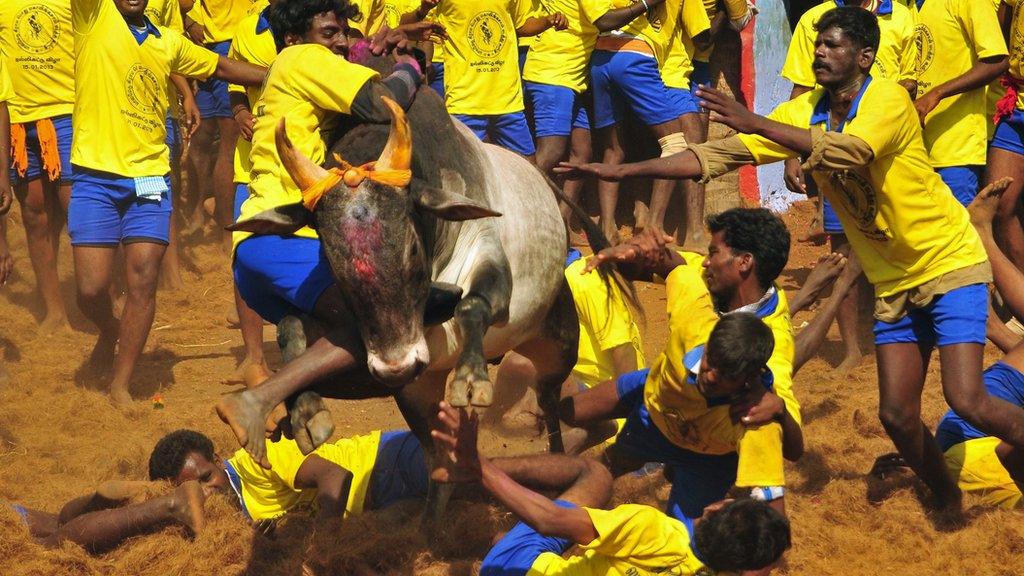

Bull owners like Pandian Ranjith (centre) say it is vital to keep traditions such as Jallikattu alive

Native cattle breeds in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu face a fight for survival if a ban on "bull-taming" contests is not revoked, say supporters of the sport.

Jallikattu has been practised for thousands of years - unlike in Spain, the bull is not killed and the object is to pluck bundles of money or gold tied to the animal's sharpened horns.

But in 2014 the sport was outlawed by the Supreme Court following objections from animal rights activists who say it is cruel. The court upheld the ban in January.

The state that loves bullfighting but isn't Spain

Only native breeds are used in Jallikattu.

"In Tamil Nadu we used to have six native breeds. One breed called Alambadi has been officially declared extinct," says bull fighting supporter Balakumaran Somu. "This ban is going to kill other breeds as well."

'Bulls not pets'

Breeders say Jallikattu and bullock cart racing gave the region a healthy male-to-female ratio of native cattle.

A bull sanctuary in Tamil Nadu

Breeders say they can't afford to keep bulls as pets

"Jallikattu inspired people to hold onto their bulls. Farmers provided extra care for the animal since the bull represents the pride of their family and community. If the ban continues there will be no incentive to hold on to the bulls," says Karthikeyan Siva Senaapathy. He is among the few breeders of pure Kangayam cattle.

The Kangayam breed is native to western Tamil Nadu and used extensively in Jallikattu.

"We had over one million Kangayam bulls in 1990. The population has fallen to 15,000 now."

Tamil Nadu is the most urbanised state in India, with a well-established manufacturing and services sector. Due to the mechanisation of agriculture and transport, the economic rationale for owning a bull has declined.

Bullock carts are seen less and less these days in Tamil Nadu

Dairy farmers, too, are turning their back on native cattle and prefer high-yielding buffaloes and cross breeds. Most of the small dairy farmers own only cows and buy in the services of Jallikattu bulls.

"Among the young calves only the best is selected for Jallikattu. Others are castrated and used to plough farmland. This ensures only the best genes get passed on," Mr Senaapathy says.

"We used to have a cow-to-bull ratio of 4:1. But now it has gone to 8:1 and it is going to slip further due to this ban. Farmers can't afford to have big bulls as pets."

Welfare

Activists claim the removal of native stud bulls from villages will make farmers depend more on artificial insemination.

Usually, old bulls are sold off. But now younger and fitter bulls are being sold to meat traders.

Jallikattu contests used to be huge crowd pullers

Bullfighting arenas in Tamil Nadu lie empty this year for the first time

Alarmed by the surge in the number of bulls being killed for meat, a non-governmental animal rights organisation swung into action and bought more than 200 bulls.

"These bulls are not protected under any law. So, we couldn't stop them from being sold for slaughter. The only option to save these animals was to buy them," says S Nizamudeen, founder of Coimbatore Cattle Care.

He is planning to offer his bulls for stud services.

"None of the bulls I bought had any major injury or signs of torture. Many farmers are selling the bull because of the uncertainty." He favours the resumption of Jallikattu under strict guidelines.

P Rajasekaran, president of the Tamil Nadu Jallikattu Federation, agrees.

"If any individual is caught doing harm to a bull, catch him and prosecute him. We have no objection to it. But don't have a blanket ban."

Most of the bulls used in Jallikattu are owned by village temples - in other words by the community. These bulls can't be sold but the fear is they may not be replaced.

But animal rights activists argue the decline of native cattle began even before the ban, due to economic factors.

"Our primary concern is the welfare of the animals not the survival of the species," says Dr S Chinny Krishna, vice chairman of the Animal Welfare Board of India. It functions under the Ministry of Environment and Forests, the prime mover behind the ban.

"Bulls were domesticated thousands of years ago. They don't see humans as enemies."

He says large numbers of bulls are already being rescued and sheltered by various animal rights groups and they are ready to do more to rehabilitate them and to help breeding programmes.

"To suggest an animal has to endure a life of cruelty just to survive is an unacceptable proposition."

'I talk to my bulls'

References to bull fighting can be found in Tamil literature dating back 2,000 years. Bull fighters are celebrated in folklore. Tamil cinema often depicts bull taming as a mark of heroism.

A decade ago some satellite TV channels started broadcasting Jallikattu events live. This helped to revive interest in a slowly declining sport and unexpectedly brought in money.

Bull tamers in some places even won prizes. But the sport also attracted more scrutiny, eventually leading to the ban.

Pandian Ranjith says bulls are "valued members of the family"

Madurai-based bull owner and tamer Pandian Ranjith accuses animal rights groups of exaggerating the situation.

"I have been taming bulls for close to 20 years now. I have been injured many times. I have seen so many bull fighters suffer serious injuries. But I've never ever seen a bull being injured."

He argues a total ban offends communities who cherish a particular way of life - a family tradition he inherited from his father and grandfather.

"I am a tech graduate and work as a network support consultant. When I come home, I go straight to my bulls and talk to them before having my dinner. We treat the bulls as valued members of our family. We can't think of harming them."

Animal rights activists disagree. They point to bulls being given substances such as alcohol to disorient them.

They have also filmed instances when tails were twisted or bitten, or the animals jabbed with sharp instruments or sticks.

But Jallikattu supporters question why there is no action against horse racing or the conditions of temple elephants.

Meanwhile, the fate of native breeds remains uncertain.

No political party in Tamil Nadu favours a complete ban on the sport - so organisers hope to find a solution through political initiatives rather than a legal reprieve before next season.

- Published12 January 2016

- Published7 January 2016

- Published7 May 2014