Concern in Kashmir over police pellet guns

- Published

Doctors say they have received more than 100 cases of eye injuries caused by pellet guns

Fourteen-year-old Insha Mushtaq, a resident of Indian-administered south Kashmir, is convulsing in pain on a bed in the intensive care unit of a Srinagar hospital, as her mother Raziya Begum sits by helplessly.

The girl's face is swollen and totally disfigured and doctors say her condition is critical.

Miss Mushtaq was hit by a volley of "pellets" - tiny pieces of metal shrapnel - that have been used against civilian protesters by Indian security forces, since unrest began after the death of popular separatist militant Burhan Wani.

Warning: Some readers may find the images below distressing

"She was with other family members on the first floor of our home that evening," her father Mushtaq Ahmed Malik told the BBC.

"I had gone to the mosque to pray. She peeped out of the window and a Central Reserve Police Force [CRPF] man fired pellets at her from a very short range."

Both Ms Mushtaq's eyes have been severely damaged and Dr Tariq Qurashi, the head of ophthalmology at the hospital, told the BBC she would not regain her vision.

"We have received around 117 such cases," he said, adding that while seven people had been blinded by pellets, another 40 had been discharged with less serious eye injuries.

What are pellet guns?

Pellet guns - a form of shotgun - were first used by the police as a non-lethal weapon to quell protests in Indian-administered Kashmir in 2010. They are usually used for hunting animals.

The gun fires a cluster of small, round-shaped pellets, which resemble iron balls, with high velocity.

A pellet gun cartridge can contain up to 500 such pellets. When the cartridge explodes, the pellets disperse in all directions.

They are less lethal than bullets but can cause serious injuries, especially if they hit the eye.

Doctors treating pellet gun wounds in Kashmir told the Indian Express newspaper they were seeing "sharp and more irregular-shaped pellets" which were causing "more damage" this time.

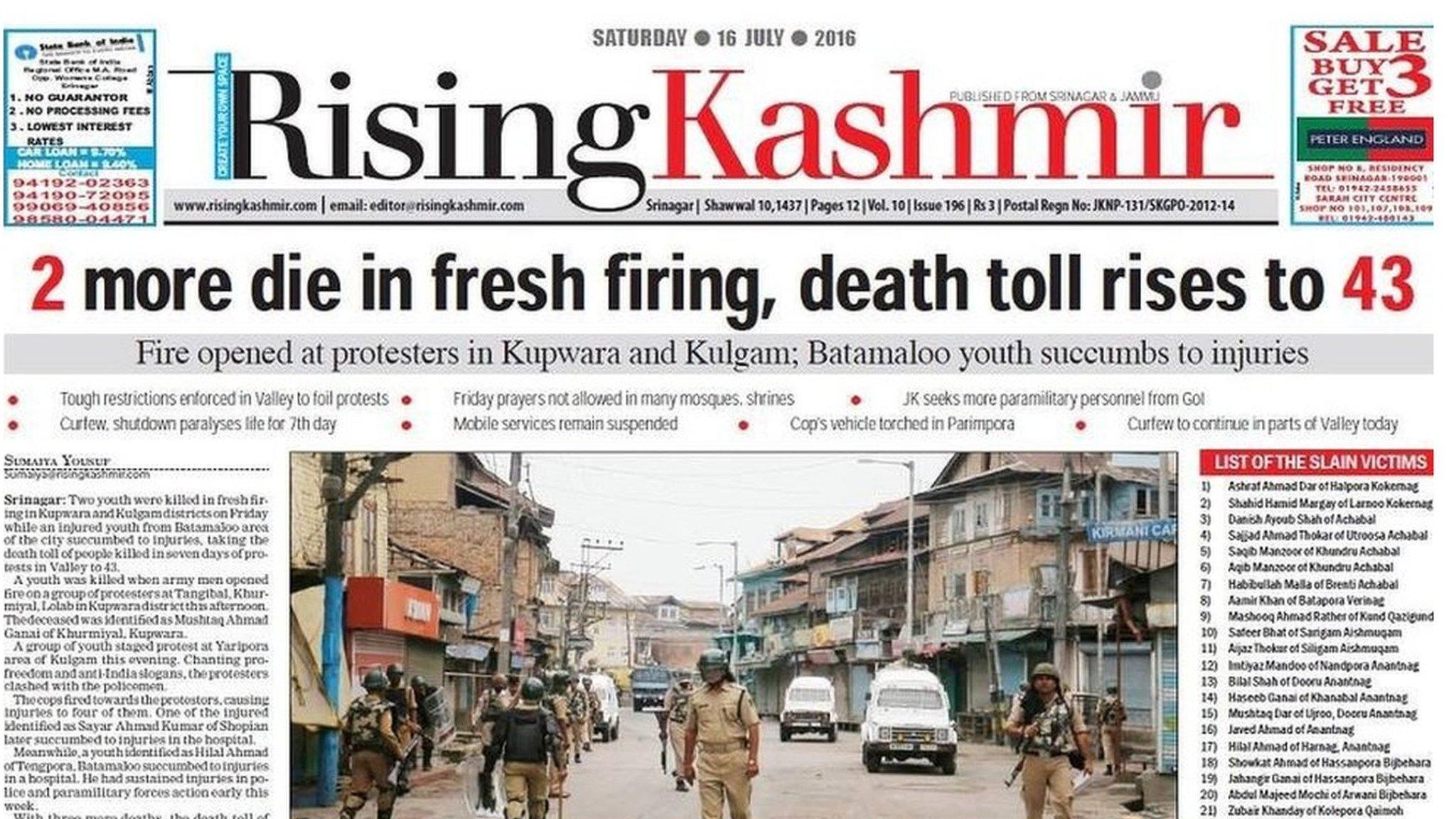

The unrest in Kashmir this time has killed more than 40 people in the region and injured close to 1,800.

The government imposed a strict curfew but crowds of mainly young people have defied orders across the region, taking to the streets in large numbers.

Security forces have been accused of using disproportionate force against civilians, a charge the state government has vowed to investigate.

'She peeped out of the window and a Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) man fired pellets at her from a very short range'

They have fired bullets, tear gas, pepper gas and, of course, the "non-lethal" pellets at protesters.

They are meant to follow Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) which calls for targeting legs in extreme volatile conditions. But more than 90% of those injured have received injuries above the waist.

Rajeshwar Yadav, a spokesman for the CRPF in Kashmir, has insisted that officers have shown "maximum restraint" while dealing with protesters.

"We use a special cartridge that has low impact and is non-lethal," Mr Yadav told the BBC.

But many disagree.

'Warlike situation'

"Government forces are deliberately aiming at chests and heads," one doctor told the BBC on condition of anonymity. "They seem to be aiming to kill."

At the Srinagar hospital where Miss Mushtaq was being treated, tales of pain and agony abounded.

A nurse was examining Shabir Ahmad Dar, 17. Doctors feared that he might lose vision in his right eye.

In a bed close to him, Aamir Fayaz Ganai, 16, told the BBC, "I was on the way to my friend's home when something hit my eye very hard."

Mr Ganai was one of the luckier ones, though, as doctors believed they could save the eye.

Pellets are less lethal than bullets but can cause serious injuries

A team of three eye specialists has also been sent to Srinagar from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), a leading Delhi hospital.

Dr Sudarshan K Kumar, who led the team, said that the nature of the injuries was so severe that it was almost as if Kashmiri doctors were dealing with a "war-like situation".

And the trauma does not stop there.

Those who have to live with the impact of eye injuries and blindness often face financial hardship, trauma and depression.

Many have to seek treatment outside Kashmir - expenses they cannot easily afford. And in most cases, the damage is irreversible.

Like in the case of Aabid Mir, 15, who suffered severe eye injuries after being hit by pellets while returning home from the funeral of a militant.

Mr Mir's family had to rely on donations to treat him. They eventually took him to a hospital in Amritsar in Punjab state.

"His treatment cost us more than 200,000 rupees [$2,979; £2,245]," he told the BBC.

Hayat Dar was completing the final year of his undergraduate degree in 2013 when he was hit by pellets.

"I had to go through more than five vitreo-retinal surgeries," he said. "I was completely blind for more than a year before I regained slight vision in my left eye. I would often ask God to kill me. It's better to be dead than to live like that."

- Published18 July 2016