Why some factory owners are celebrating India's child labour bill

- Published

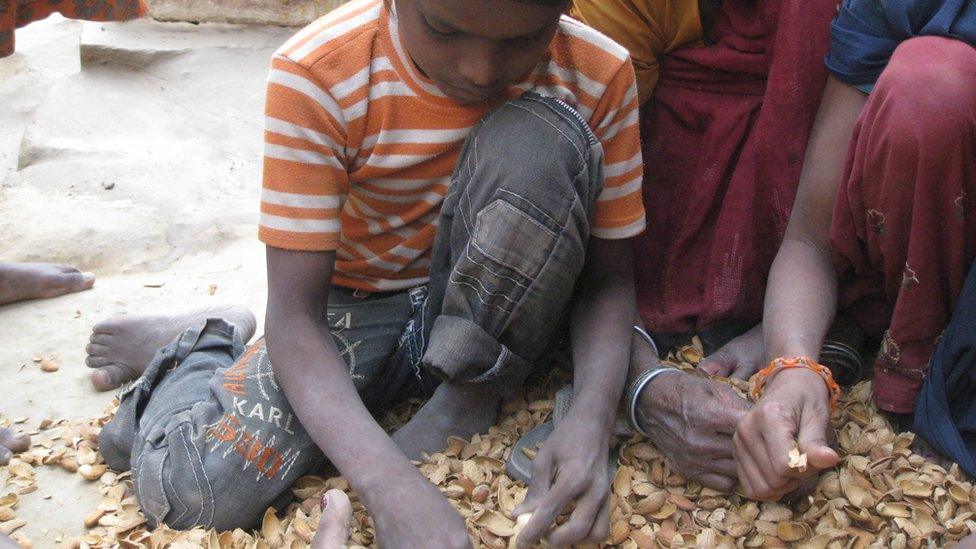

Many children work in their homes doing jobs such as shelling almonds

It's mid-morning and the local school in the large Delhi shantytown that I'm visiting, on the edge of India's vast capital, is teeming with children. The narrow lanes ring out with their little voices reciting the alphabet at the top of their lungs.

But just next to the school, that reassuring sound and sight is replaced with something else.

Doors lead off the narrow lane on which it's located to small homes.

From inside one of them, you can see groups of women squatting on the ground and bent over, peeling and sorting out piles of almonds.

Working alongside them are several children, painstakingly separating shells from husks before adding the almonds to the pile.

But even as we try to look in, our way is blocked by a man who wants to know what we want.

"Please leave, you have no permission to look inside," he says when I tell him we are journalists.

We are hurried along.

There are many almond-processing factories in other houses in the neighbourhood which is a thriving hub of small businesses.

Ironsmiths, furniture makers, seamstresses and costume-jewellery makers ply their trade in the homes that dot the area.

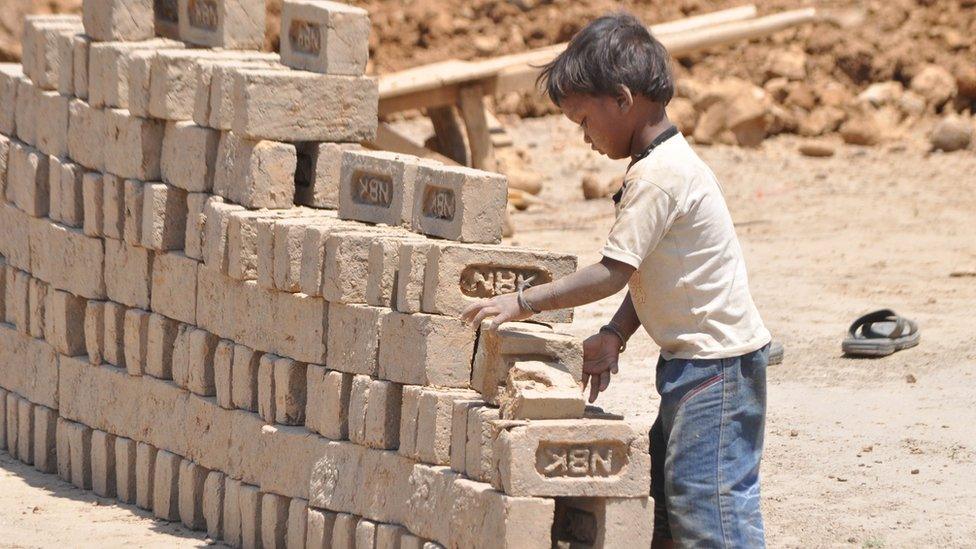

Factory owners say they pay underage labour much lower wages

Under a new, controversial child labour law that has just been passed by the Indian parliament, children younger than 14 are barred from working.

But a provision says they may work after school hours and on holidays in the sports or entertainment industry or in family enterprises.

Exploited

"It's really good news," says Rajinder, one factory owner who agreed to speak to us.

"Earlier I could only hire someone aged above 18. Now I can employ more people."

And children cost less.

"I pay my workers 300 rupees ($4.50; £3.50) a day. But I pay an underage employee only 100 rupees ($1.50) a day. It's a big saving."

He is also not very concerned about the provision that such work can only take place within the family.

"How long does it take to acquire a family?" he asks. "It's not a big problem."

This is exactly what child rights' activists and critics of the new law fear - that it will be exploited and used to drive even more children out of school and into work.

Some experts believe mere laws cannot get rid of child labour

"There is no clear definition of who a family is," says Bidisha Pillai, Advocacy Director of the British charity Save the Children.

"It's not just the mother and father. It could be a uncle, aunt, brother, sister."

Ms Pillai says the new law encourages many industries to push production out of factories into homes, which makes it harder to monitor.

But the government says that while framing the new law, it had to delicately balance the need to protect children with the reality that millions of poor Indian families depend on the wages their children bring in.

Long-term answers

Many of these families work in agriculture or in artisanal trades, and the government says children will get the opportunity to acquire traditional skills.

Many like commentator Gurcharan Das, who has written a number of books on the Indian economy, says mere laws cannot get rid of child labour.

"Eventually child labour will go away because of growth," he says.

"The long-term answer is economic development. India has had high growth for 15 years or so and if we have high growth for another decade or two, I think we will, organically, wipe out child labour.

The sight of children working is something that confronts you all across India.

At traffic signals children sidle up selling flowers.

Many work as domestic help.

Others wait on tables at little restaurants or teashops.

And then there are the invisible ones - working in factories, in mines or on the farm.

The new law is unlikely to put an end to child labour.

The hope is that it can regulate it.

The fear is that it will only increase it.

- Published27 July 2016