Olympic losers: Why is India so bad at sport?

- Published

Dipa Karmakar is the first Indian woman gymnast to qualify for the Olympic Games

"We have never won a medal for running," says the Indian sprinter Dutee Chand, "but with God's grace I will get to the finals and I will win one."

If the fastest woman in India succeeds, it will be a breakthrough for Indian sport.

The world's second most populous nation has the worst Olympic record in terms of medals per head.

In the past three decades, it has won only one gold medal - for the men's 10m rifle in 2008.

In London, in 2012, it bagged its best haul, six medals, or one for every 200 million people.

In 2008, it got just three medals. Before that, it was lucky to come home with a single medal.

Compare India's performance with minnows such as Grenada and Jamaica, which regularly get a medal for every couple of hundred thousand people.

So why isn't India punching its weight?

One reason is undoubtedly money.

India, despite its space programme and burgeoning population of billionaires, is still a very poor nation in terms of per capita income, and sport has never been a priority for the government, according to Shiva Keshavan.

Keshavan is far and away India's greatest Winter Olympian.

He competes in luge, a kind of super-fast sledge. In two of the past five Winter Games, he was the only Indian to qualify, the only member of a team of one. Yet his ticket to Sochi was paid not by the Indian government but by crowdfunding.

Dutee Chand will be the first Indian woman sprinter in 36 years to participate in the Olympic 100m

And the lack of government - or any other - funding has also seen Keshavan adopt an eye-poppingly dangerous training regime.

There are no luge facilities in India, so he screwed wheels to the bottom of his sledge and practised on Himalayan roads, external, overtaking cars and lorries to reach speeds of up to 100km/h. (62mph)

"At one point I couldn't sustain my career," says Keshavan.

"I couldn't go for training, I couldn't go for competitions because I didn't have the money for that, so I started looking for sponsorship. And I actually went to 100 companies before one of them said yes."

He believes the chronic lack of resources has undermined his performance, and that of most other Indian athletes.

"I think to be sustainable we have to have a proper system for athlete selection and training from a young age," he says.

The Indian Olympic Association admits the country has not always done enough to support its athletes, but says there is more to India's sorry performance than just a shortage of cash or organisation.

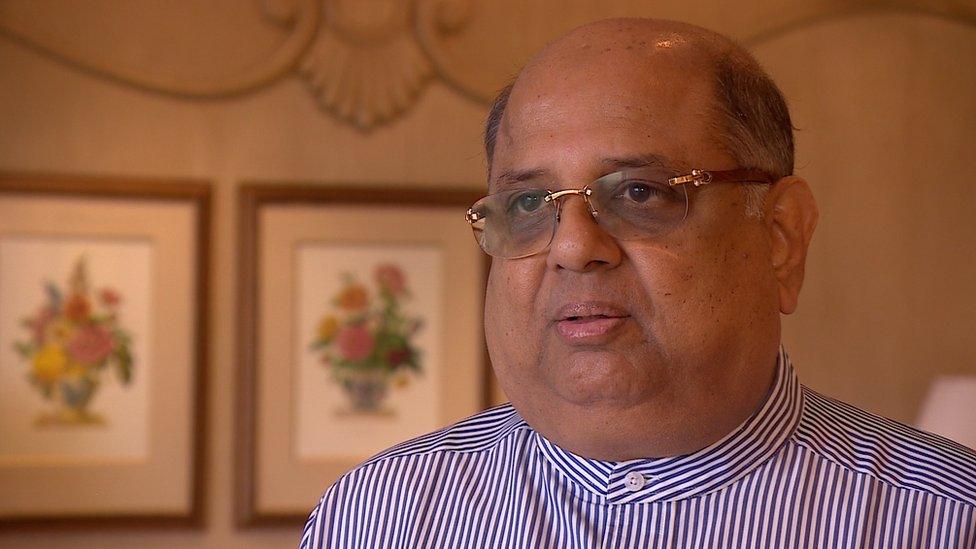

Its head, Narayana Ramachandran, says sport is rarely at the top of anyone's agenda - and that includes athletes and their families.

"Sport has always taken a back seat vis a vis education," he says.

Most Indian families would prefer their children became dentists or accountants than Olympians, Mr Ramachandran says.

"Families tend to give their children more education," he says.

"The view is concentrate on education, rather than sport. The basic feeling is that sport doesn't bring the money that is required to run a family."

India's cultural and caste traditions play a role too, according to Prof Ronojoy Sen, of the University of Singapore.

He has written a book on the history of sport in India and believes the country's poor Olympic record has deep roots.

Indians have traditionally seen themselves primarily not as individuals, but as members of their caste, tribe or region, he says.

Even when people excel in sport, they are often discouraged from pursuing it to top levels, by their families and wider community.

And social stratification has meant different castes tended not to play sport together.

"The lower castes constitute the bulk of India's population, and these lower castes are also the ones who don't have access to education, don't have access to good nutrition, health," Prof Sen says.

Indian Olympic Association president Narayana Ramachandran says sport struggles to find a role in the country

"That has meant that a large part of India's population hasn't been able to take part in sport, and hasn't had access to sporting facilities."

There is one sport in which India does, of course, excel: cricket. The huge money professional teams can invest means the best athletes are almost inevitably drawn towards the wicket, draining the pool available for other sports.

Now, private companies are stepping in to try to fill the gaps in funding for Olympic sports.

They are following the example of countries such as Australia and the UK, which have dramatically increased their medal count by investing in elite selection and training programmes.

It has been estimated that each medal the UK won in 2012 cost £4.5m, external.

Maneesh Bahuguna, of Anglian Medal Hunt, which is funding a number of predominantly disprivileged athletes, including Dutee Chand, believes its efforts will - in time - deliver results.

"What we bring to the table for these athletes is the ability to bridge the gap between those best practices that are unavailable to them otherwise and the final performance at the Olympic Games," Mr Bahuguna says.

"We improve their conditioning, physical and mental, by leaps and bounds."

India is fielding its best-trained and biggest-ever team in Rio.

It is hoping to deliver on the promise of the country's vast population, reaping rewards on the winner's podium.