India climate: What do drowning rhinos and drought tell us?

- Published

This week I went to the scene of terrible tragedy.

A river, swollen by raging monsoon floodwaters, had torn down a bridge on the main road between Mumbai and Goa.

More than 30 people are thought to have died when the great stone structure crashed into the torrent, taking with it two buses and a number of cars.

Some of the bodies were swept more than 60 miles downriver in two days.

More than 150 rescuers and divers searched for survivors

We produced a short news report.

In the heart-wrenchingly brutal calculus of the newsroom, this isn't a major story. But zoom out, and you begin to see the outlines of a much bigger and more worrying picture.

India, indeed the whole South Asia region, has been riding a rollercoaster of extreme weather.

The summer monsoon is the most productive rain system in the world, and this year the region is experiencing a strong one. The floods it caused have affected more than 8.5 million people; more than a million are living in temporary shelters; some 300 people have been killed.

Though what really caught people's interest was the three baby rhinos rescued from the waters in the north Indian state of Assam.

Wildlife officials rescued three baby rhinos

The fact that 17 adult rhinos drowned got rather less attention.

But the important point is that the region is awash with water. Just a few months ago, it was a very different story. The previous two monsoons were unusually weak. The result was a terrible drought in northern India, and parts of Pakistan and Bangladesh.

And it was exacerbated by another extreme weather event - record heat.

India experienced its highest temperature ever this summer, a blistering 51C.

Rivers ran dry; water holes evaporated; reservoirs became dusty plains. And, once again, the statistics were staggering.

More than 300 million people were affected by water shortages - the equivalent of the entire population of the US. A city of half a million people was left completely dry. It had to rely on supplies brought in by train.

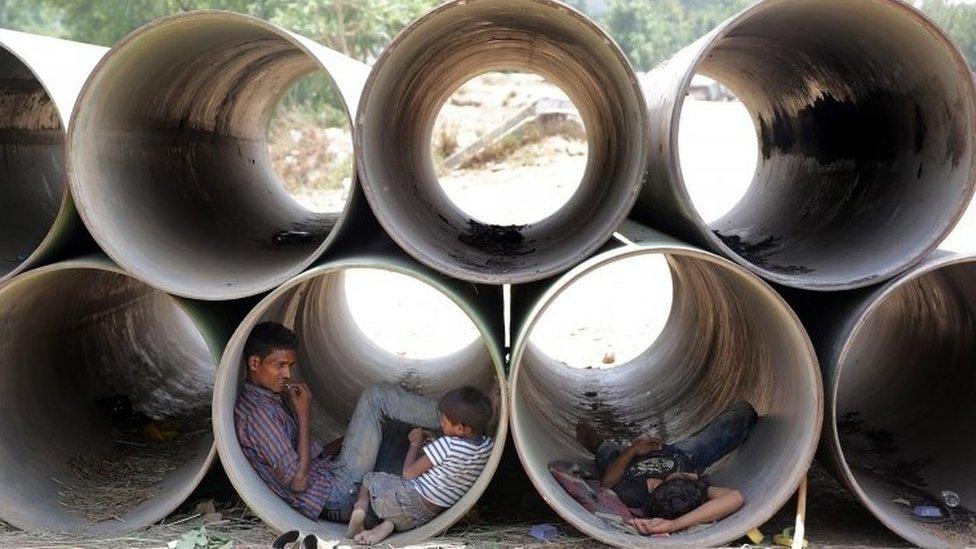

Unused water pipes provide shelter from the heat in May's record temperatures

As if that weren't bad enough, in spite of the drought, the country was hit by a series of unseasonal rain and hailstorms, external. They caused such terrible damage to crops that some farmers were driven to suicide.

All these examples of extreme weather were widely reported, rightly so. What tended not to be discussed was the underlying cause.

We are all interested in weather; few of us want to be told - once again - that our lifestyles are disrupting the global climate. Yet the truth is that many climatologists believe the monsoon, always fickle, is becoming even more erratic as a result of global warming.

The picture in the last couple of years is complicated by the fact that the world has been experiencing a particularly strong El Nino, the periodic weather variation caused by warming of the sea in the Pacific.

But a series of long-term studies have shown the number of extreme rainfall events, external in South Asia increasing while low-to-moderate events are decreasing. And increasingly erratic and extreme weather is precisely what scientists expect climate change will bring.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has predicted "rainfall patterns in peninsular India will become more and more erratic, with a possible decrease in overall rainfall, but an increase in extreme weather events".

Mumbai struggled through heavy monsoon rain showers in June

Since the monsoon accounts for as much as three-quarters of rainfall in some areas, any change is a huge issue. The more extreme the storms, the more likely we are to see more tragedies like the shattered bridge I visited this week.

Now, since you've read this far, I hope you'll excuse me if I take a moment to ram my point home a little harder because there is growing evidence that climate change isn't just restricted to South Asia.

Ask anyone who follows the issue and they'll tell you that this year is already well on the way towards becoming the hottest ever. The previous record was last year; before that it was 2014. In fact, the 11 warmest years have occurred since 1998.

I'm not saying we shouldn't talk about the weather, just that we need to talk about the climate too.