What happened to Mother Teresa's sceptics?

- Published

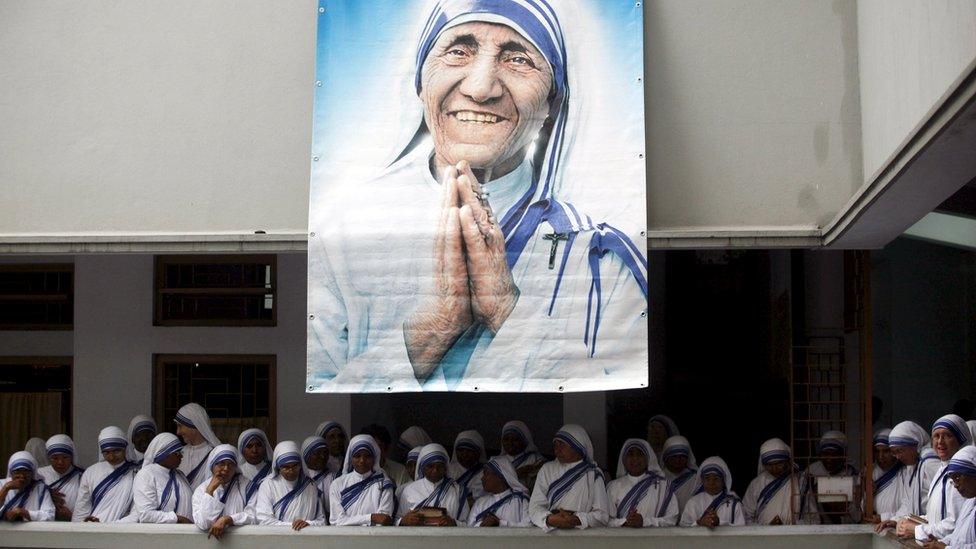

The Nobel laureate nun, who died in 1997, founded the Missionaries of Charity

When Mother Teresa, the Roman Catholic nun who worked with the poor in the city of Kolkata (Calcutta), is declared a saint on Sunday, her critics will be insisting that faith has triumphed over reason and science.

The Nobel laureate nun, who died in 1997, aged 87, founded in 1950 the Missionaries of Charity, a sisterhood which has more than 3,000 nuns worldwide. She set up hospices, soup kitchens, schools, leper colonies and homes for abandoned children and was called the Saint of the Gutters, for her work in the city's heaving slums.

She has also her fair share of critics.

Maverick British-born author Christopher Hitchens described her as a "religious fundamentalist, a political operative, a primitive sermoniser, and an accomplice of worldly secular powers".

In the much-talked about pamphlet The Missionary Position, Hitchens criticised the nun's "cult of suffering" and said she had painted her adopted city as a "hell hole" and hobnobbed with dictators. Hitchens also presented Hell's Angel,, external a sceptical documentary on the nun.

Much later, in 2003, London-based physician Aroup Chatterjee, external published a blistering critique of the nun, after conducting some 100 interviews with people associated with the nun's sisterhood. He flayed what he called the appalling lack of hygiene - reuse of hypodermic needles, for example - and shambolic care facilities at their homes, among other things.

Pope John Paul II beatified Mother Teresa in 2003

There are others like Miami-based Hemley Gonzalez, who worked as a volunteer in one of Teresa's homes for the poor in Kolkata for two months in 2008, and was "shocked to discover the horrifically negligent manner in which this charity operates and the direct contradiction of the public's general understanding of their work".

Questioning miracles

"Standing firm against planned parenthood, modernisation of equipment, and a myriad of other solution-based initiatives, Mother Teresa was not a friend of the poor but rather a promoter of poverty," Mr Gonzalez told me. Today, he runs a Facebook page, external criticising the nun and to educate "unsuspecting donors" to the sisterhood.

In recent years, Indian rationalists like Sanal Edamaruku have questioned the miracles that have led to the nun's sainthood.

To become a saint in the eyes of the Vatican, a miracle needs to be attributed to prayers made to the individual after their death. Incidents need to be "verified" by evidence before they are accepted as miracles. Often they are cures and recoveries from illnesses which have no logical medical explanation.

More than 3,500 nuns are now part of the Missionaries of Charity sisterhood

Monica Besra claimed that a photo of the nun cured her of her cancer

Five years after the nun's death, Pope John Paul II accepted a first miracle - the curing of Bengali tribal woman Monica Besra from an abdominal tumour - and judged it was the result of her supernatural intervention. This cleared the way for her beatification in 2003. Pope Francis recognised a second miracle in 2015, which involved the healing of a Brazilian man with brain tumours in 2008.

'Tawdry'

Mr Edamaruku has debunked the first finding, external, wondering how a woman could be cured by a photo of the nun placed on her stomach, when there was evidence to suggest that medicines treated her. Today, he says, "most people don't want to challenge the nun any more because of her image as somebody who worked for the poor".

"If you question Mother Teresa you are seen as anti-poor. I have nothing against her, but miracle-mongering is not scientific."

And an evidently exasperated Chatterjee told me that the "so-called miracles are too tawdry and puerile to challenge even".

The nun remains an icon in Kolkata after her death

The latest challenge has come from a group of academicians and social workers who have petitioned Indian Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj to reconsider her decision to visit the Vatican to attend Sunday's sainthood ceremony.

"It boggles the mind that the foreign minister of a country whose constitution exhorts its citizens to have scientific temper would approve of a canonisation based on 'miracles'," the petition said.

But, in the end, as sociologist Shiv Visvanathan says, proof and faith are different things. "Lots of questions are still open. Many of us have a poor sense of the history and philosophy of science. Christianity also has a long history of battles with science. Rationalists also can sometimes end up overdoing things by demanding evidence all the time," he says. Clearly, the jury is still out on the Saint of the Gutters.