In pictures: India's dying Christian communities

- Published

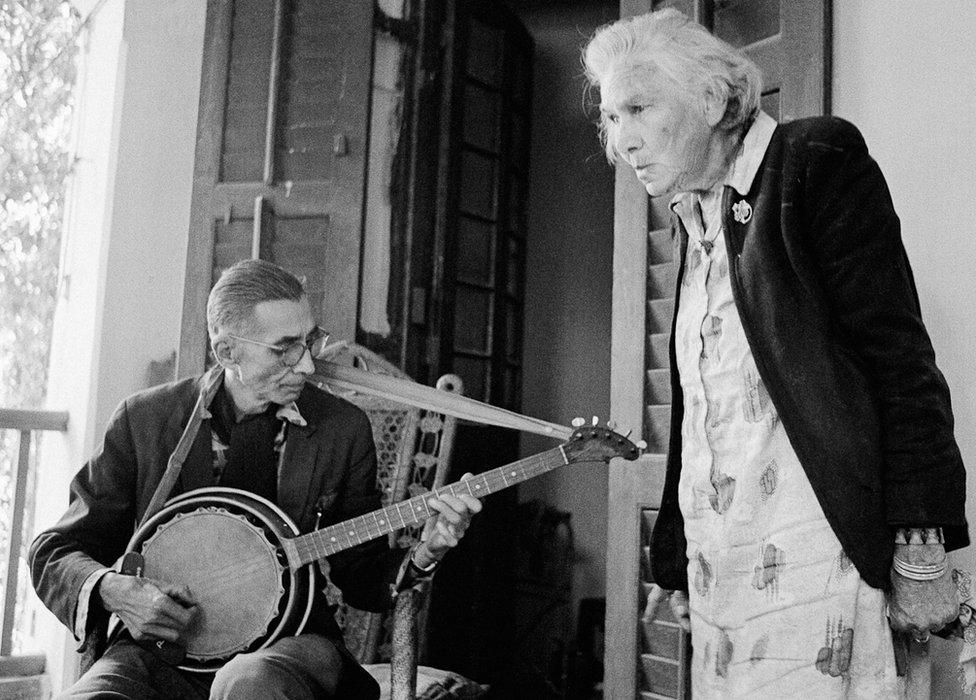

Mr and Mrs Carpenter, Tollygunge, Kolkata, 1981

London-based photographer Karan Kapoor has recorded some of India's dying Christian communities who are trying to preserve their identities in rapidly changing times.

One of the communities he has photographed extensively are the Anglo-Indians. A product of the British Empire, with a mixture of Western and Indian names, customs and complexions, several thousand Anglo-Indians live in India.

The son of well-known actors Shashi Kapoor and the late Jennifer Kendal-Kapoor, Kapoor himself is of both Indian and British descent.

The other community he has chronicled are the Goan Catholics, probably the largest inheritors and defenders of their Portuguese heritage.

Most of his pictures were taken in the 1980s and 1990s and they focus on people and places that have either been lost to history, or changed beyond recognition.

India's Tasveer gallery is holding an exhibition - and has published a book - of Kapoor's works titled Time and Tide.

Tollygunge home, Kolkata, 1981

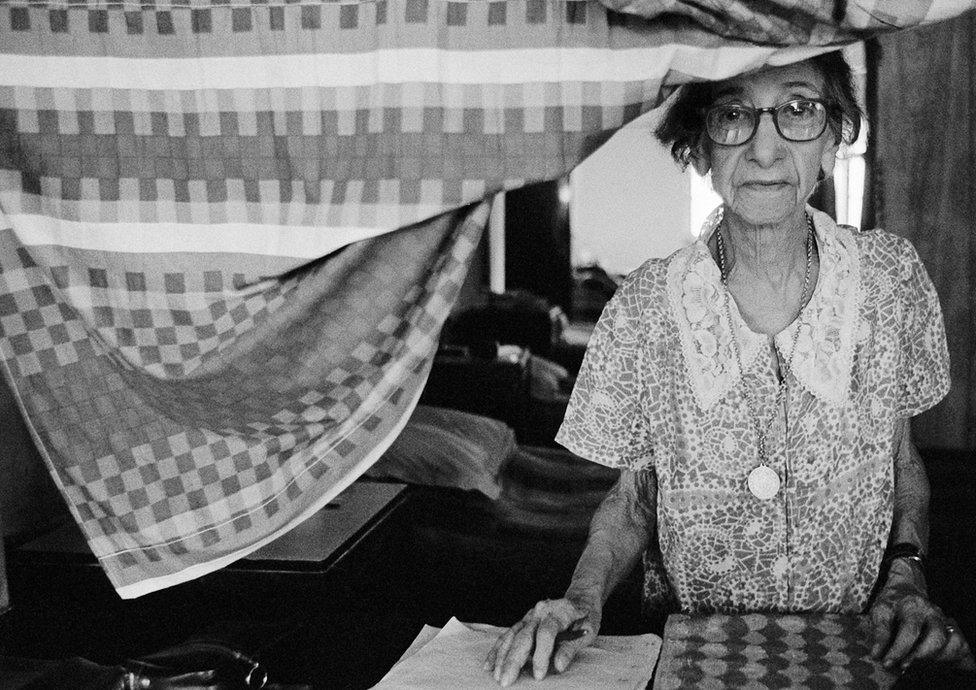

Kapoor was drawn to the subject of ageing Anglo-Indians, primarily from the cities of Mumbai and Kolkata. He began by studying the older residents of a home for Anglo-Indians in Kolkata.

"I was more interested in the older generation as they seemed to be the last remaining remnants of the British Raj - people who remembered the railway cantonments, the Marilyn Monroe look-a-like contests, the 'Central Provinces', and so on, a world long gone," writes Kapoor.

Lovers Lane, Byculla, Bombay

"No one could be better qualified to record the Anglo-Indians than Karan Kapoor, and with these extraordinary images he has in many ways, taken the photographs he was born to shoot," says author and historian William Dalrymple.

Andheri, Mumbai, 1981

Mr Carpenter, Tollygunge, Kolkata, 1981

Thousands of Anglo-Indians left after India after independence.

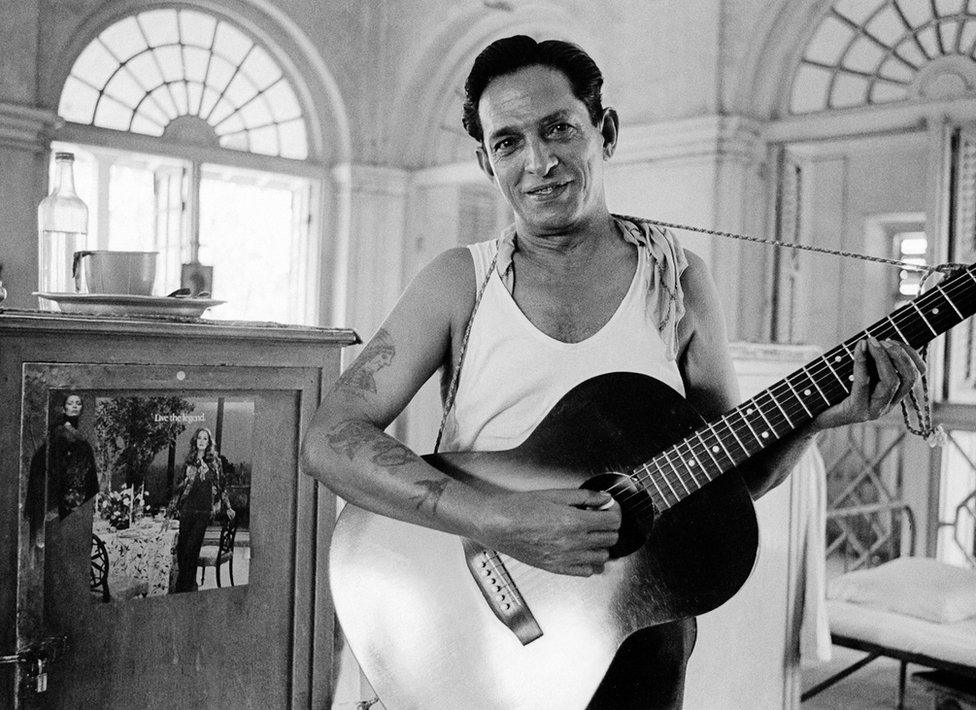

"The rump who had remained in India - the optimistic, the old or the nostalgic, the faded beauties and the aging banjo players, with their 1950s tattoos and bow-ties, so movingly shot by Kapoor - stayed on in the face of some Indian resentment, and an increasing degree of poverty.

"The younger generation, especially the girls, tended to intermarry and were able to blend in; but others, particularly the older ones, found it hard to change their ways.

"It is these people with their frocks and tweed suits and Homburg hats, their Union Jacks and their memorabilia of the Royal Family, the old couples wandering under their umbrellas, that Kapoor has so beautifully recorded and commemorated," writes Dalrymple.

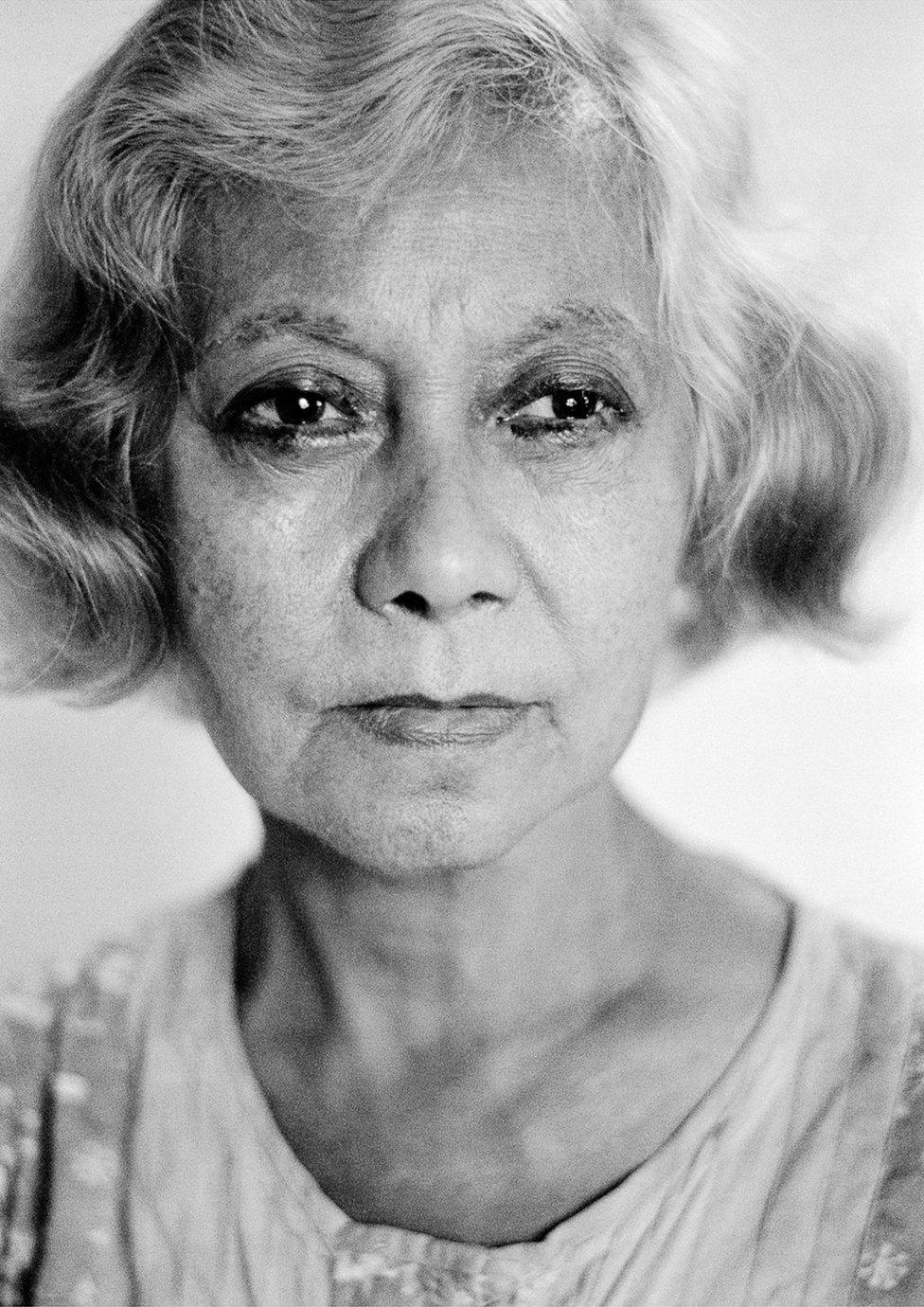

Violet, Andheri, Bombay, 1982

Kapoor also took portraits of Goa's Catholic community.

"On our holidays to Goa, I would end up riding around on my Royal Enfield, exploring the countryside, my camera always with me," he says.

Taken in the 1990s, these photographs capture an older Goa: the last of 'Portugal Goa'.

For just over 14 years after India won independence from the British in 1947, Goa remained under Portuguese rule.

Emiliano's House, Loutolim, Goa, 1994

Blind musician being led at a local feast, Loutolim, Goa, 1994

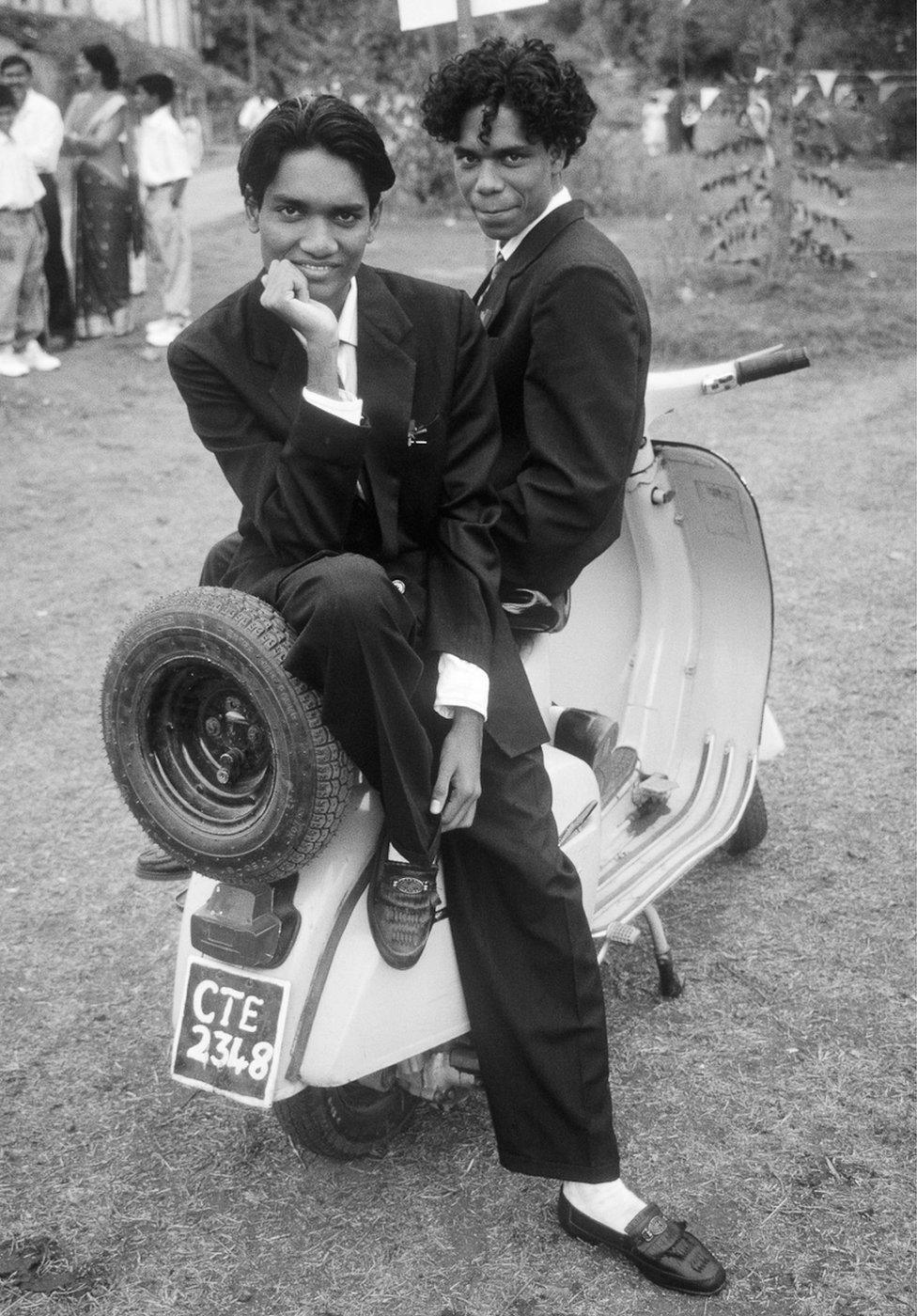

Young men at a Goa feast, 1994

Loutolim, Goa, 1994

Rachol seminary, Goa, 1994