Can training 'fake doctors' improve India's healthcare?

- Published

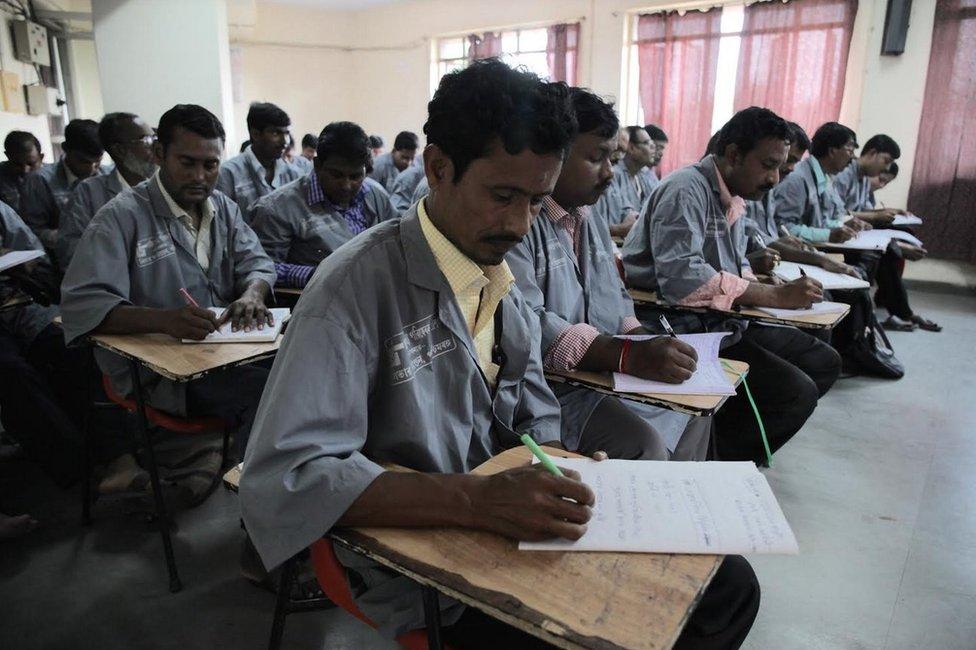

Charity group Liver Foundation is training unqualified medics in India

Unqualified medics, popularly known as quacks, are routinely arrested in India for posing as doctors. But a charity is now trying to train them in primary medical care. Atish Patel explains why.

Sanjoy Mondal opened his small clinic with just a desk and a few plastic chairs in eastern India 15 years ago, after a short stint assisting a doctor working at a government hospital.

Although he has not studied medicine, Mr Mondal says he has conducted countless minor surgeries and prescribed drugs to hundreds of patients in a village of mud-walled homes in West Bengal state.

Now, the 40-year-old is one of thousands who have been taught the basics of front-line care by a non-governmental organisation which wants to ensure patients aren't harmed by self-taught medics.

"I now understand what safe drugs and what unsafe drugs are," Mr Mondal says, boxes of pills piled up behind him on shelves hammered into the sky-blue walls of his dark, dingy clinic.

Liver Foundation, external, the Kolkata-based charity offering the training, says most of India's medical establishment will criticise such a programme because they think unqualified practitioners are the bane of the country's healthcare system.

Serious shortage

In recent weeks, in southern Tamil Nadu state, authorities launched a crackdown after several children died reportedly after seeking treatment from unqualified medics.

Anil Bansal, a former head of the anti-quackery section of the Delhi Medical Council, external, which registers and oversees the Indian capital's doctors, says "they are cheating the general public" and breaking the law.

But the Liver Foundation's founder, Abhijit Chowdhury, believes they should be utilised because India faces a chronic shortage of qualified doctors and medical staff.

A new study published last week in Science magazine has assessed the effectiveness of the foundation's training programme.

Sanjoy Mondal, left, says he gives basic medical care to people in his village

The Healthcare Federation of India says the country has a shortfall of nearly two million doctors and four million nurses. It is most prominent in rural swathes where it is estimated that more than 60% of primary care visits made by villagers are to fee-charging unqualified practitioners like Mr Mondal.

In Banbataspur village where he works, villagers say they turn to him because the free primary health centre, several kilometres away, is understaffed and open for just a few hours a week. Mr Mondal says he has treated locals for common illnesses like hypertension, diarrhoea and anaemia.

Sanghamitra Ghosh, secretary at West Bengal's state health and family welfare department, admitted it was difficult to retain doctors in remote areas and says unqualified medics are "filling a gap" in an "overburdened healthcare system".

More than 100,000 unregistered freelancers practise self-taught medicine in West Bengal, home to some 90 million people. Across India, there's an estimated one million - meaning there are more fake doctors than real ones.

Mixed results

"I'm more confident in my job," Mr Mondal said about the training he received, which lasted nine months with two classes each week.

But has it reduced the risk of medical errors?

The new study out last week showed mixed results.

It used so-called "mystery clients" trained to pose as patients suffering from three conditions - chest pain, asthma and child diarrhoea. How to detect these ailments were among the things taught to those who had undergone training.

To compare care, the mystery clients were sent to trained and untrained informal providers, as well as doctors working in government clinics.

India has one of the worst doctor-to-patient ratios in the world

The study found that although those who had taken the Liver Foundation course were more likely to adhere to checklists after training and made big improvements in providing correct treatments, it did not affect the unnecessary doling out of antibiotics and other drugs.

This is worrying and "one of our goals - harm reduction - in that sense, was not achieved," said Dr Chowdhury, who co-authored the paper along with World Bank economist Jishnu Das, Abhijit Banerjee from MIT and Yale University's Reshmaan Hussam.

But the team discovered the situation was worse among trained physicians.

They found unqualified providers - trained or untrained - were less likely than doctors at public clinics to give out unnecessary antibiotics and medicine - reinforcing findings from earlier studies.

What could explain this?

Well for one, the study's authors say, medical knowledge among trained doctors varies dramatically because of differences in the quality of training given at India's medical schools. Second, along with high levels of absenteeism, low effort among doctors working in rural India remains a problem.

A study published last year, external and conducted in the central state of Madhya Pradesh found that because untrained providers spent longer with patients than government doctors on average, they performed no worse on diagnoses and treatment.

Fake doctors mostly work in rural areas

In other words, what untrained providers lack in terms of classroom time, they made up for in patient contact.

Giving incentives to government doctors is of course one approach to rectify this, but the new study's authors point out that efforts in the past have proved difficult.

'Grounds for optimism'

With this in mind, and the reality that rural public healthcare infrastructure is scarce (for example, West Bengal has 909 primary health centres in total, far short of the required 2,166, according to official statistics, external) training quacks - already with a large presence across India - could be more viable and cost-effective, the authors say.

There is "some grounds for optimism", they said, because "training was sufficient to improve the clinical practice of the most regular attendees to the point where the performance of these informal providers matched that of better-trained, but presumably poorly motivated, public sector doctors".

They added that training fake doctors "offers an effective short-run strategy to improve health care".

The West Bengal state government has said it will make this model a reality. Since 2007, it has funded the Liver Foundation's classes in Birbhum - one of the districts in the state where training has been offered.

"Training is expected to be scaled up by December and offered to thousands more informal practitioners across the state," says Dr Chowdhury.

"They will be known as village health workers and not doctors."

But it's likely to face serious resistance. In the past, the Indian Medical Association, a membership organisation for registered doctors, has taken legal action and successfully stopped similar schemes. The same could happen in West Bengal.