How a 105-year-old ended open defecation in her village

- Published

Kunwar Bai Yadav has become famous in and around her village for building a toilet in her home

On Tuesday, Dhamtari became the first district in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh to be declared free from open defecation. And the credit for that is being given to Kunwar Bai Yadav, a woman who claims to be 105, and sold her only assets - a few goats - to build a toilet at home. The BBC's Geeta Pandey visits her home to hear her inspiring story.

A mere 100km (60 miles) from Raipur, the capital of Chhattisgarh, is Kotabharri village where 18 families, displaced by a dam on the Mahanadi river, were settled in the late 1970s.

The small non-descript village seems to be an unlikely setting for a revolution and its oldest resident, Kunwar Bai Yadav, seems like an unlikely revolutionary.

But in the past year, Mrs Yadav has put her name - and that of her village - in bold letters on the state's journey towards becoming free from open defecation.

The toilet cost Mrs Yadav 22,000 rupees ($330; £271)

Mrs Yadav claims to be 105 years old

Today, she is a local celebrity, much sought after by her fellow villagers and senior government officials who describe her as their "mascot" in the campaign to end open defecation in the state.

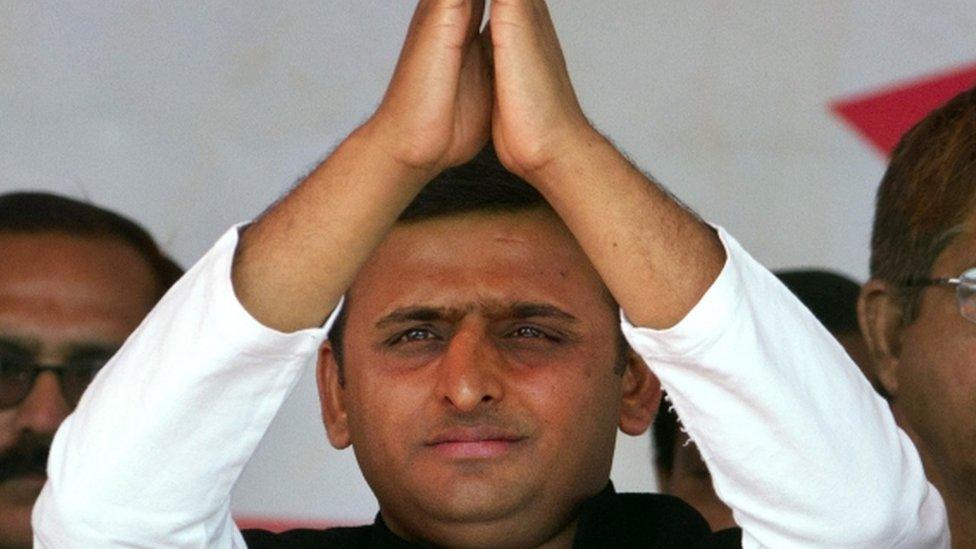

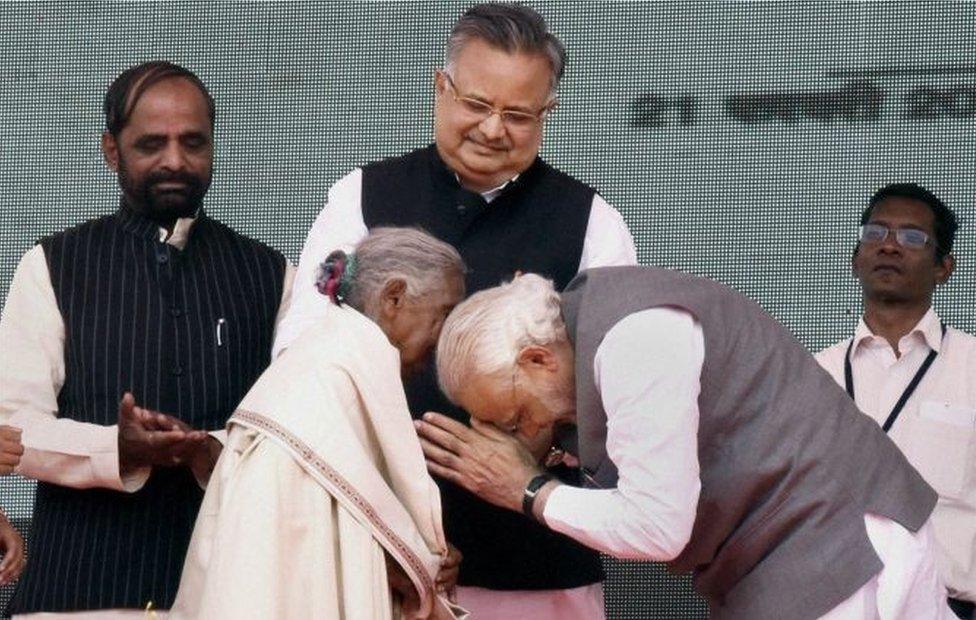

Earlier this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi bowed before her and touched her feet to express his appreciation for her work. On Tuesday, Mr Modi is returning to the state to declare Dhamtari as open defecation free.

You might also like

So how did Dhamtari, home to 800,000 people, get to this point? Ask this question of anyone in the state, and they point at Mrs Yadav.

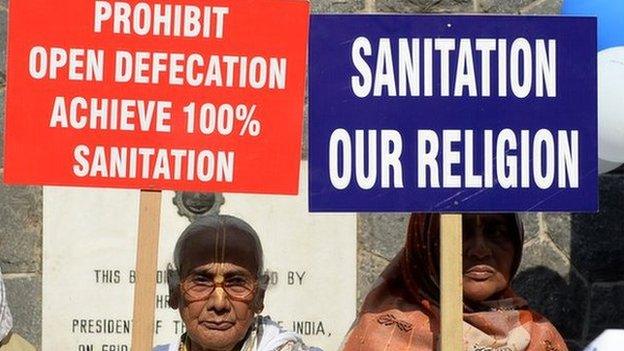

Two years ago, Mr Modi's government launched the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (Clean India Campaign) with a key aim to eliminate open defecation in the country by 2 October 2019 - the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi.

Earlier this year, Mrs Yadav was felicitated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi

Kunwar Bai Yadav sold seven of her goats to raise money to build a toilet

India was shamed into action when official figures showed that 550 million people - nearly half of India's billion plus population - defecated in the open. The fact that more people had access to mobile phones than toilets invited much ridicule about misplaced priorities.

The authorities began a massive campaign to encourage people to build toilets and government officials were sent into the remotest areas to tell people about the benefits of ending open defecation.

And that's how Mrs Yadav, who had for a century gone out in the nearby forests to defecate, heard about toilets last year for the first time in her life.

"The district collector was visiting the local school to give a speech. I also went along and there he talked about building toilets. Until then, I had no idea about toilets and never thought about it," she told me. "But what he said, set me thinking. It sounded like a good idea."

Mrs Yadav is recognised for her contribution to the Clean India Campaign

Kunwar Bai Yadav is poorer than most of her neighbours

Mrs Yadav has had no formal education and in the absence of any birth certificate, it's impossible to corroborate her claim that she's 105, but her heavily lined face, stooped frame and failing eyesight are a testimony to the times she has lived through.

In recent years, she says she's been finding it difficult to do the daily trek to the forest for her ablutions and had fallen twice and hurt herself.

"I thought if I somehow built a toilet at home, it would save me a lot of trouble," she says.

"But I had no money so I started thinking about how I was going to pay for it. My only assets were the 20-25 goats I owned, so I sold seven of them for 18,000 rupees [$270; £222]. As I was still short of funds, my daughter-in-law who works as a daily-wage labourer pitched in and we managed to raise enough money to build a toilet," she explains.

Mrs Yadav lives with her daughter-in-law and other members of her family

She has received much accolade for building a toilet at home

Four hired labourers worked over 15 days to build the toilet which cost her 22,000 rupees ($330; £271).

The toilet, the first in her village, soon became a talking point with her neighbours who came around to look at it. Within weeks, farmers from nearby villages also started dropping by and soon, many started building their own toilets. Within a year, every single home in the village had a toilet.

"Initially most villagers were unwilling to build toilets at home because they were used to going in the open," says Vatsala Yadav, the village council head for Kotabharri and Barari villages.

"Kunwar Bai took the lead and everyone in her village followed. And then, it spread to Barari where until last year, only 60 of the 338 homes had toilets. Now every single house has built toilets," she adds.

In Mrs Yadav's village, those found defecating in the open are asked to pay a fine of 500 rupees

"Earlier, people would say, 'we are too poor, how can we build a toilet'," says Johan Singh Yadav, insurance agent and Vatsala Yadav's husband.

"But Kunwar Bai has shut everyone up. She's poorer than most others here and now people say, 'if she can do it, so can we'. She has provided a solution."

Building toilets, however, is no guarantee that people would use them and the biggest challenge, says Dhamtari district collector CR Prasanna, is changing the mindsets.

"People are used to going in the open and old habits die hard. I can build toilets, that's the easy part, but changing mindsets is much harder."

"Kunwar Bai took the lead and everyone in her village followed," says Vatsala Yadav, the village council head for Kotabharri and Barari villages

To tackle that problem, authorities have appointed "green armies" where groups of men and women go out in the mornings and evenings - when most villagers head to the fields and forests - to check open defecation.

Street plays are being organised to teach people about sanitation and people like Mrs Yadav are being roped in to encourage others to follow their example.

Mrs Yadav, who lived her entire life in obscurity and had never stepped out of her village until earlier this year when she was invited to meet the prime minister, is getting used to her new celebrity status.

Officials say now every house in Dhamtari district has a toilet now

"All my life, I'd leave home in the morning to graze my goats or work as a daily wage labourer. I gave birth to 12 children, many of them died while still young. Over the years, I've lost eight of them and my husband. The poverty was crippling, we struggled daily with hunger to survive," she says, adding, "I never imagined I would become so famous one day."

That fame, Mr Prasanna says, is richly deserved.

"She has inspired an entire state. And since the prime minister bowed before her, she has become a household name in Chhattisgarh.

"She's our mascot for the Swachh Bharat campaign. She's our poster girl," he says.

- Published30 August 2015

- Published11 March 2015

- Published17 June 2014

- Published29 October 2016

- Published29 October 2016

- Published28 October 2016

- Published26 October 2016