The Indian tribesmen catching giant snakes in Florida

- Published

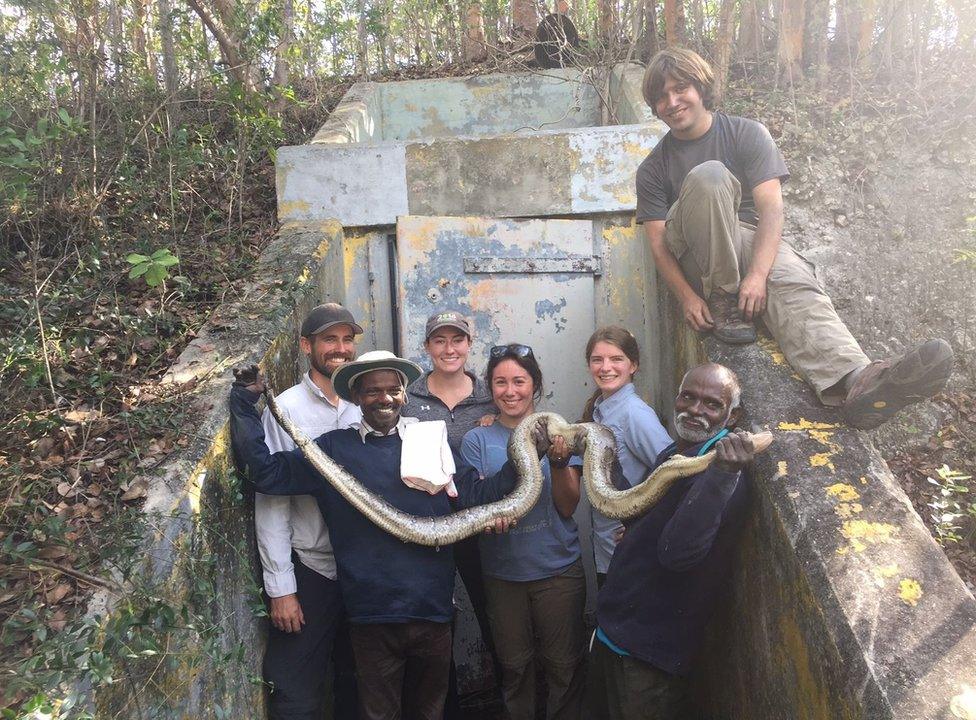

Masi Sadaiyan and Vadivel Gopal have caught 27 pythons in Florida so far

Every morning, two Indian tribesmen in T-shirts and long trousers, leave their dwellings in southern Florida and head into the Everglades to hunt for some of the world's biggest snakes.

Masi Sadaiyan and Vadivel Gopal, members of the once-nomadic Irula tribe, are armed with crowbars and machetes. Wearing fleece jackets and baseball caps, they slash and wade their way through the largest subtropical wilderness in the world to hunt down Burmese pythons.

The non-native snakes - which escaped into the wild in Florida or were released as pets - pose the biggest threat to the small mammal population of the national park. They also eat birds, alligators and deer. In 2005, a Burmese python tried to swallow an alligator and exploded in the park,, external leaving both the predators dead.

Ever since the pythons were spotted in the wild more than two decades ago, authorities have tried everything to catch the elusive snakes in the marshes, but with limited success.

They have used pythons (called Judas snakes) to find other pythons during the mating season, asked people to turn in their pet snakes, poisoned prey, and even encouraged people to hunt them for a cash prize.

Last year, some 1,000 hunters participated in a competitive month-long Burmese python hunt , externalto rid the wetland of the invasive species, and caught 106 snakes.

By comparison, in the past four weeks, the two 50-something tribesmen from India have caught 27 pythons, including a 16ft-long (5m) female in an abandoned missile base in Key Largo. Pythons that are caught are later put down.

Burmese pythons

Burmese pythons (Python bivittatus) have several common names, including Asiatic rock python and black-tailed python

They are native to India, lower China, the Malay Peninsula and some islands of South and Southeast Asia

The snakes - which usually reach up to 3m (about 12 feet) in length, but can be more than 5m long - have secured a foothold in the southeast US, after pet snakes were released, or escaped, into the wild

They are now considered a threat to biodiversity in the Florida Everglades

"Masi and Vadivel are doing an incredible job. They excel at determining if pythons are present at a site, locating them if they are, and then catching them when located," Frank Mazzotti, a biologist at the University of Florida who heads a team of researchers investigating pythons, told me.

"They can see pythons even when they are covered by grass. All they need is a glint of snake and they pounce. The rest of us are usually wondering where the snake is. Next thing we see they are holding it."

The Miami Herald, external marvelled at the snake-hunting skills of the Irulas, whom herpetologist Rom Whitaker describes as the "best snake catchers" in the world. The newspaper reported that the Irulas appeared to have "mysterious" tracking techniques.

"They move slowly and rather than focus on roads and levees where snakes have typically been found basking, they head straight for thick brush. The Irulas believe the boulders and high grasses that line the levees are more lucrative hunting grounds.

"And when the going gets slow, everyone must stop to squat for a quick song of prayer - usually an ancient invocation mixed with an ad lib about pythons or the weather - accompanied by a beedi cigarette."

Their biggest catch as been a 16ft-long female python in an abandoned missile base

Writer and film-maker Janaki Lenin, who is accompanying the tribesmen, has provided a gripping account, external of the female python they recovered in Key Largo. The two men cut the roots that blocked the entrance to the bunker, pried open a door, went inside, poked the snake, broke through a concrete shaft and hauled out the 75kg (165lb) reptile.

Another time, a eight-foot-long python, according to Ms Lenin, "struggled and emptied its bowels" on Masi, who held the tail. "After the Irula bagged the python, the grinning but impressed Americans held their noses with their fingers, miming how stinky the snake faeces were," she recounted.

Masi said he was not bothered. "Only if you are covered in it, can you catch snakes."

For the past month, the two men, who have travelled around the world to catch snakes, have been living in the home of Joe Wasilewski, a well-known herpetologist. Their two months of work is funded by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

After an oatmeal breakfast, they are driven to work. Sometimes they go out after dark. In the early days, they survived on Trinidadian Indian food, but since then they have tried hotdogs and burgers and watched an NFL game.

"All that they say so far is that they like being in America and want to catch lots of pythons," Ms Lenin said.

Masi and Vadivel, members of an ancient tribe, have become unlikely globe-trotting snake-catchers. Last July, they went to Thailand to help researchers implant radio transmitters for their study, and ended up catching two king cobras.

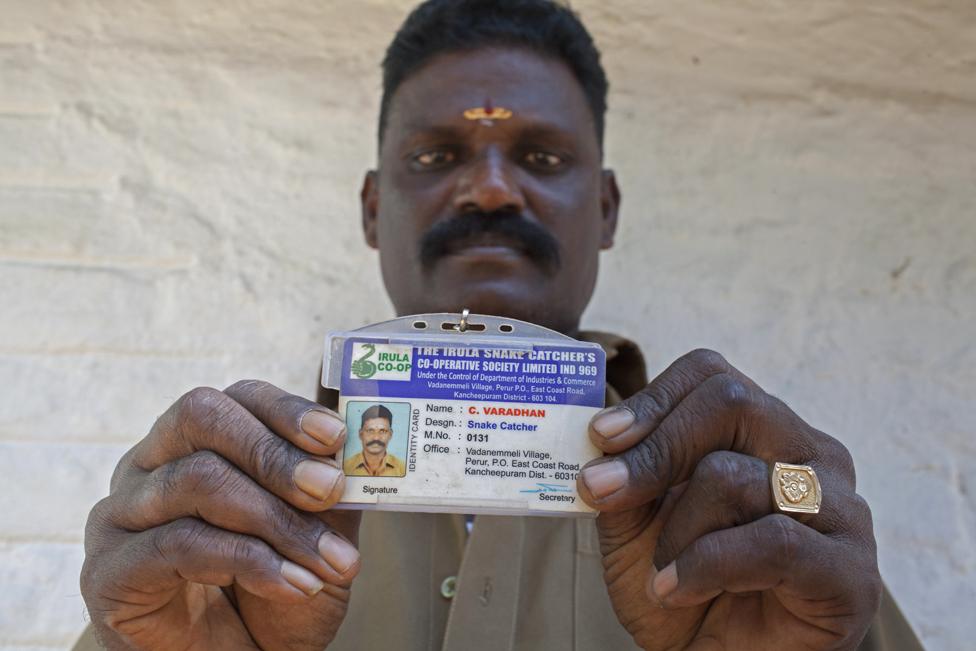

Back home, the men are part of a thriving 35-year-old co-operative of community members, who catch snakes and extract and sell their venom for a living. India is home to 50 species of venomous snake and bites kill some 46,000 people a year, accounting for nearly half the snakebite deaths in the world.

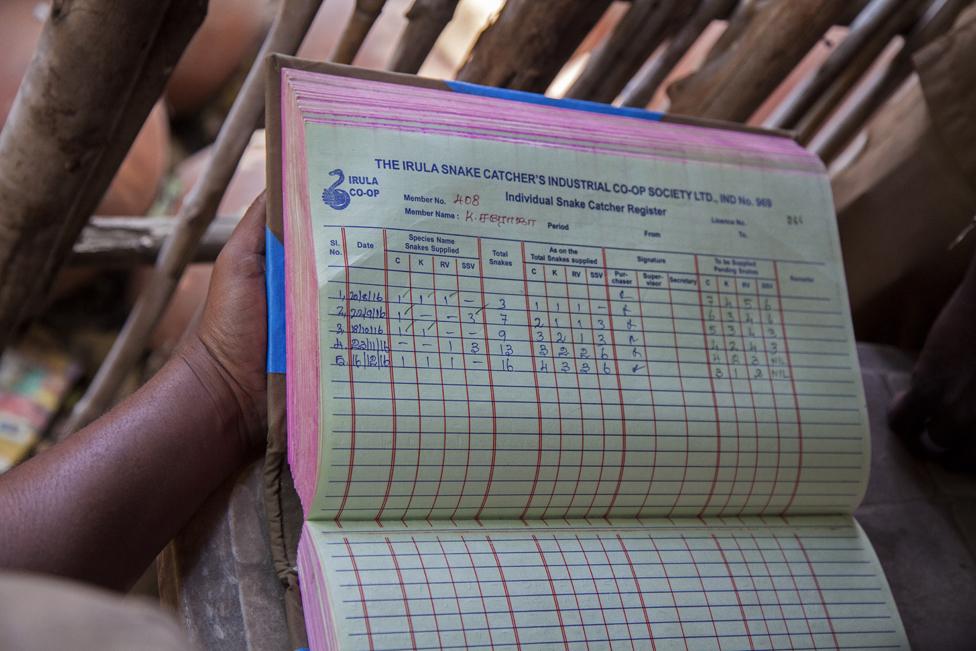

The Irulas have a government licence to catch 8,300 snakes in India every year

A co-operative of Irula snake catchers has 370 members, including 122 women

Venom is extracted from each snake four times a month

There are more than 850 poisonous snakes in the co-operative farm

The Irulas poached snake and lizard for their skins until the trade was outlawed in 1972. A decade later, they formed a co-operative near the southern city of Chennai and switched to catching poisonous snakes - mainly cobras, kraits and vipers - to extract and sell venom. The venom is now sold to seven laboratories, who manufacture most of India's anti-snake venom serum.

Last year, the co-operative's 370 members, including 122 women, sold snake venom worth 30 million rupees ($446,500; £357,900), up from a mere 6,000 rupees in 1982.

They have a government licence to catch 8,300 snakes every year - each snake is released in the wild after four extractions in a month - but demand they are allowed to catch three times as many.

After all, a gram of cobra venom sells at 23,000 rupees today, nearly eight times as much as the price in 1983. An Irula snake-catcher earns some 8,000 rupees every month, apart from other health and pension benefits.

Last year, the co-operative sold snake venom worth 30 million rupees

The snakes are kept in earthen pots filled with sand and covered by white cloth

This Irula snake-catcher lost his finger after a cobra bite

"We are illiterate and poor. We don't own land. Snakes have saved our lives," says K Ravi, an Irula. But most of them say their children want to move to the big cities and get a "company job". The daughter of an Irula couple is the first collegiate in the co-operative, and is training to become a nurse.

It is not clear whether this will be the last generation of these snake-catchers, a community of 116,000 tribespeople. For many, that would mark the passing away of a traditional hunting skill.

"They are better at the above than any other snake catchers that I have known," Mr Mazzotti says.

"Think of [the game of] cricket. What is the difference between really good amateurs and professionals? The Irulas are professionals."