Bhanwari Devi: The rape that led to India's sexual harassment law

- Published

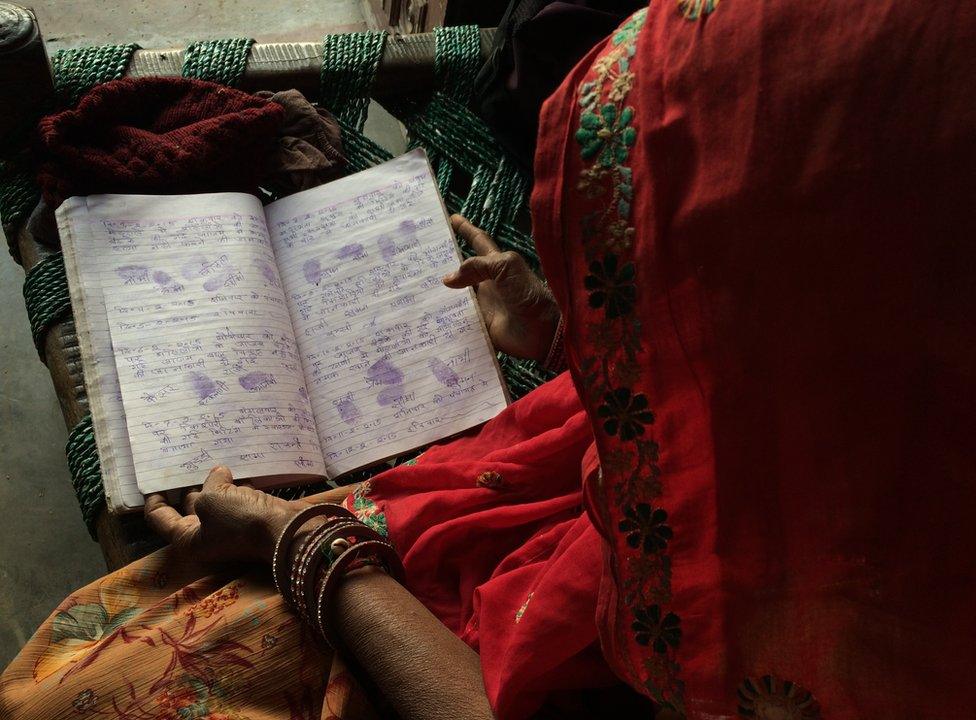

Bhanwari Devi is a grassroots government worker

Bhanwari Devi is an unlikely heroine.

Nearly a quarter of a century after the illiterate, low-caste woman was allegedly gang-raped by her high-caste neighbours in the western Indian state of Rajasthan, she refuses to give up her fight for justice.

It was her case that resulted in the Indian Supreme Court formulating guidelines to deal with sexual harassment in the workplace, but her attackers remain free, cleared of rape charges by the trial court while her appeal has been heard just once in the high court over the past 22 years. In the interim, two of the accused have died.

The attack took place on 22 September 1992 and with the passage of so much time, Bhanwari Devi, now 56, no longer remembers the days and dates clearly, but the memory of the assault is still vivid in her mind.

"It was dusk. My husband and I were working in our fields when they started beating him up with sticks. There were five of them," she told me when I visited her at home in Bhateri village, 50km (about 30 miles) from the state capital, Jaipur.

She ran to help her husband, pleading with the men to show some mercy, but two of the attackers pinned him down, while the remaining three took turns to rape her.

Pioneering Indians

Pioneering Indians is part of the India Direct series. It looks back at men and women who have helped shape modern India. Other stories from the series:

The attackers were Gujjars, the affluent and dominant caste group in the village. Bhanwari Devi and her husband, Mohan Lal Prajapat, are from the low-caste potter community, Kumhar.

The men were angry with her for trying to prevent a nine-month-old Gujjar girl's wedding a few months earlier.

Bhanwari Devi had worked as a saathin (friend) for the state government's Women's Development Programme (WDP) since 1985, says Jaipur-based women's rights activist Prof Renuka Pamecha.

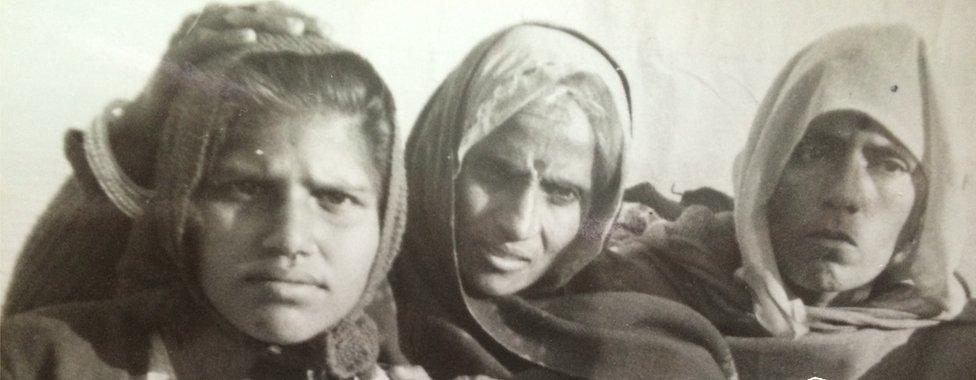

Bhanwari Devi was assaulted in front of her husband Mohan Lal Prajapat

Bhanwari Devi shows off her work register

Her job involved going door-to-door in the village, campaigning against social ills - she would tell women about hygiene, family planning, the benefits of sending their daughters to school, and she would discourage female foeticide, infanticide, dowry and child marriages.

Rajasthan has a huge tradition of child marriages and thousands of children, many just months old, are married off every year.

Bhanwari Devi herself was a child bride - she told me she had been married when she was five or six and her husband was eight or nine.

Her campaign against child marriage was not an attempt to challenge patriarchy or fight the feudal mindset, but she was just doing her job.

And she knew that meddling in the affairs of the Gujjars could invite a backlash, says Dr Pritam Pal, who headed the WDP's training programme and worked very closely with Bhanwari Devi.

But, Bhanwari Devi says, she had no choice in the matter.

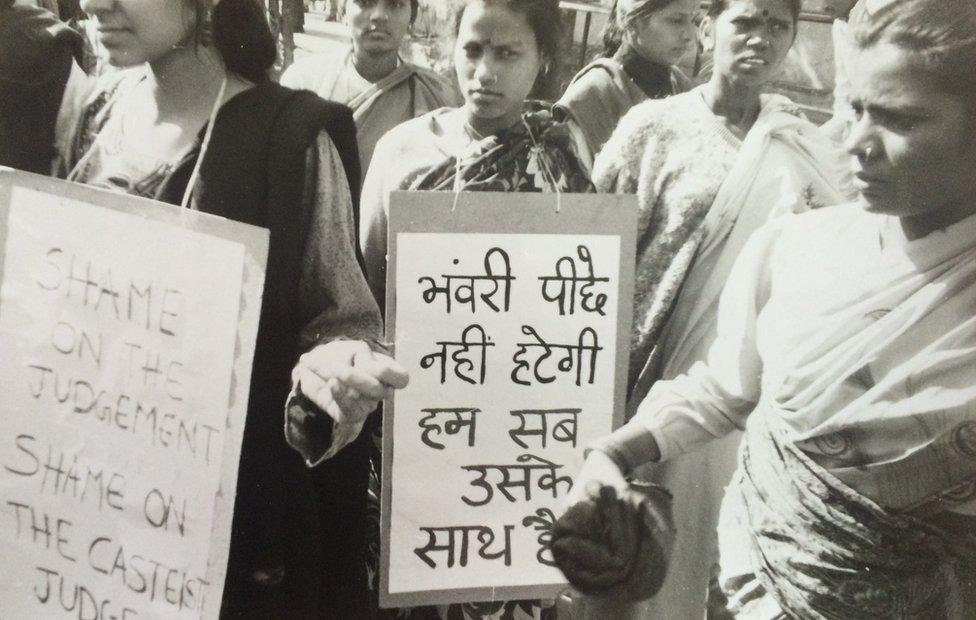

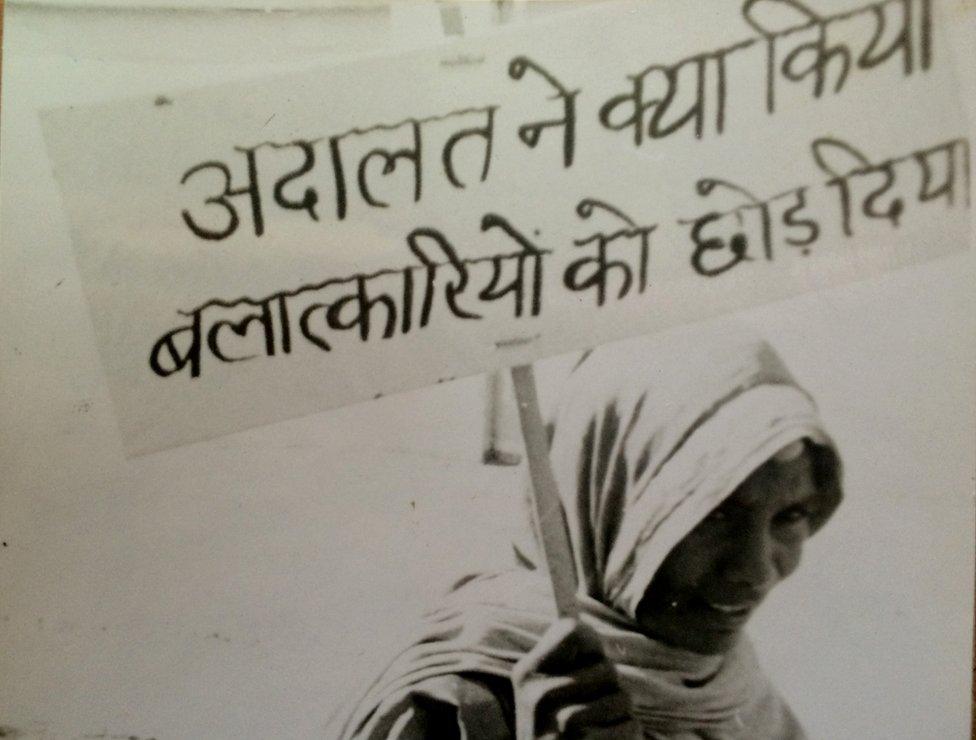

Massive protests were held in Jaipur with thousands marching through the city streets, demanding justice for Bhanwari Devi

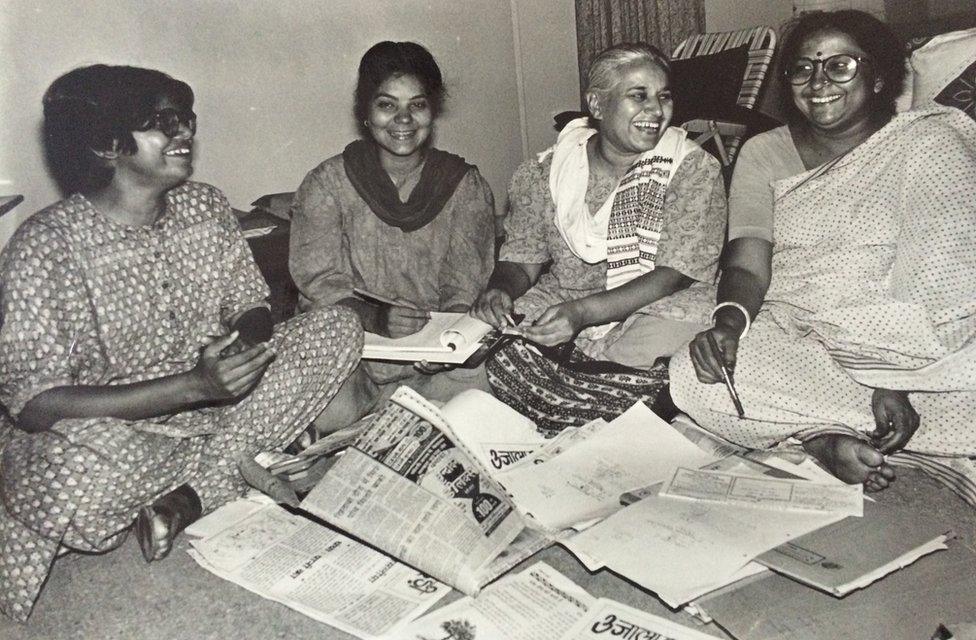

Many women's rights activists in Rajasthan have worked tirelessly for years to help Bhanwari Devi

"I told the officials that these people were dangerous and that they would come after me. But they said we had to stop all child marriages and a policeman was sent to stop the wedding. But he came, ate wedding sweets, and left."

The family accused her of humiliating them, and still managed to marry off the baby the next day - then seething with anger, they came after Bhanwari Devi.

In India's conservative society, even now victims of rape often hesitate to talk about their ordeal because of the shame and stigma associated with sexual crimes. Twenty-five years ago, the situation was worse.

"But Bhanwari Devi is nothing if not a fighter," says Dr Pal.

When she went public with her complaint, she was accused of lying. Her attackers denied rape and said there had only been a quarrel.

A rally was held in Jaipur on 15 December 1995 to protest against the acquittal of the rape accused

When Bhanwari Devi (centre) went public with her complaint, she was accused of lying

Dr Pal says the police treated her with derision, didn't take her complaint seriously and botched up the investigation. Her medical test was conducted 52 hours later when it should have been done within 24 hours, her scratches and bruises were not recorded, her complaints of physical discomfort were ignored.

After local newspapers reported Bhanwari Devi's plight and protests by women's activists, the case was handed over to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), India's federal police.

The five accused were finally arrested more than a year after the crime, and were charged with harassment, assault, conspiracy and gang rape.

While denying them bail in December 1993, Rajasthan high court Judge NM Tibrewal wrote in his order: "I am convinced that Bhanwari Devi was gang-raped in revenge for attempting to stop the marriage of [one of the accused] Ramkaran's daughter, a minor."

The judgement acquitting the accused men caused immense outrage in India and globally

Things, however, went downhill for Bhanwari Devi from there. Over the course of the trial, judges were inexplicably changed five times and, in November 1995, the accused were acquitted of rape - instead, they were found guilty of lesser offences like assault and conspiracy and were all given just nine months in jail.

"It was a dubious judgement," says Bharat of the Jaipur-based NGO Vishakha, one of the groups fighting to get justice for her. He cites some of the "bizarre reasons" the judge gave while clearing the accused of rape:

The village head cannot rape

Men of different castes cannot participate in gang rape

Elder men of 60-70 years cannot rape

A man cannot rape in front of a relative - this was with reference to two of the men, an uncle and nephew

A member of the higher caste cannot rape a lower caste women because of reasons of purity

Bhanwari Devi's husband couldn't have quietly watched his wife being gang-raped

The judgement caused immense outrage in India and globally. Massive protests were held in Jaipur with thousands marching through the city streets, demanding justice.

Congress party MP from Rajasthan Girija Vyas called the decision "politically motivated". Mohini Giri, who was then head of the Indian government's National Commission for Women, said the court order "ignored principles of justice" and wrote a letter to the chief justice appealing to him to "intervene".

Dr Pritam Pal described Bhanwari Devi as a fighter

The state government, which seemed reluctant to appeal against the order, finally challenged it in the Rajasthan high court, but only one hearing has been held in 22 years.

Prof Pamecha says justice has remained elusive for Bhanwari Devi, but she is the reason why millions of Indian women are now legally protected against sexual harassment in the workplace.

"The state authorities had refused to help her, saying as her employer, they were not responsible since she was assaulted in her fields. We said the government must take responsibility since the attack on her was because of her work."

So a group of activists from Jaipur and Delhi-based organisations filed a public interest petition in the Supreme Court, demanding that "workplaces must be made safe for women and that it should be the responsibility of the employer to protect women employee at every step".

Bhanwari Devi's plight was covered by the local media

In 1997, the top court came out with Vishakha Guidelines, external, laying down norms to protect women from sexual harassment in workplaces.

"It was a revolutionary judgement based on the fundamental rights of women. And the guidelines later became the basis for a 2013 law passed by the Indian parliament to prevent sexual harassment of women at the workplace," says Prof Pamecha.

"Bhanwari Devi had no direct role in this law, but she was the catalyst for this, she was the main factor," she adds.

"Bhanwari is a very brave woman," says Dr Pal. "The couple were ostracised by the villagers who refused to sell them milk or buy their clay pots. Even their families boycotted them.

"She didn't even get invited to family weddings. But I have never seen a moment when she said she wouldn't fight. She has always wanted justice."

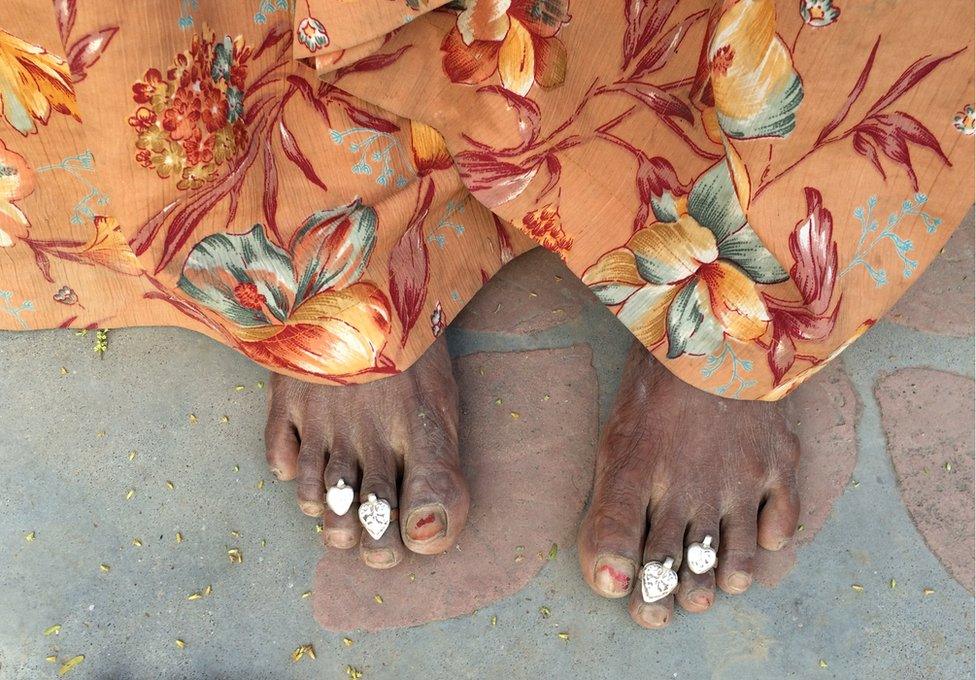

She continues to live in the same village as her attackers

Over the years, she has won several awards for her exceptional courage, most recently being recognised by the Delhi Commission for Women on 8 March.

But she continues to live in the same village, still carrying on her work as a saathin, still hoping for justice.

I ask her and her husband if they ever feel afraid?

"Not for a minute," she answers fiercely. "Didn't you just walk into my house when you came here today? Would I leave my doors unlocked if I was afraid?" she asks.

Her husband Mohan Lal adds: "What is there to fear? They can kill us only once."