Could making the Ganges a 'person' save India's holiest river?

- Published

'Mother' Ganges: India's river becomes a legal person

A court in India has declared the Ganges river a legal "person" in a fresh effort to save it from pollution. Research associate Shyam Krishnakumar explains how the ruling could help preserve the waterway upon which so many depend.

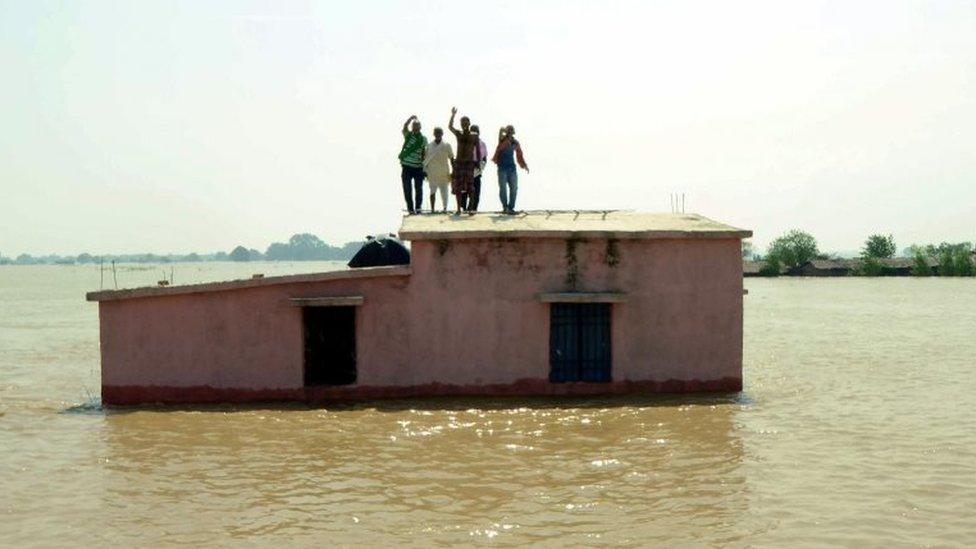

The legal battle to save the Ganges, the lifeline of more than 500 million people across India, has received a fresh boost thanks to a series of rulings by the high court in the north Indian state of Uttarakhand.

First the court declared the Ganges and Yamuna rivers to be legal persons. In a subsequent hearing, it also gave this designation to glaciers, including Gangotri and Yamunotri (where the Ganges and Yamuna originate from), rivers, streams, rivulets, lakes, air, meadows, dales, jungles, forests wetlands, grasslands, springs and waterfalls.

These verdicts represent a shift from a view that sees nature as a resource to one that considers it an entity with fundamental rights. Other non-human entities that have legal personalities in India include companies, temple deities and trusts.

In jurisprudence, nature is considered property with no legal rights. Environmental laws only focus on regulating exploitation. But this is now changing, with calls for the inherent rights of nature to be recognised, both in India and around the world.

The Ganges is seen as sacred by Hindus

In Ecuador, a new constitution mandates that nature has the right to exist, maintain and regenerate. New Zealand recently granted the Whanganui River personhood status, the culmination of a 140-year legal struggle by the Maori people.

Making nature a legal entity means that cases can be brought up directly on its behalf. This has the potential to become a game-changer in legally enforcing environmental protection.

For instance, it may no longer be necessary to prove in court that polluting the Ganges actually harms humans. Contamination on its own could be enough to make the case that it violates the river's "right to life".

In addition to this, in a related order, the court imposed a blanket ban on new mining licenses for four months and has set up a committee to explore the environmental impact of mining in India's mountainous regions. The Uttarakhand state government is planning to challenge the ban in the Supreme Court.

But it is not just mining. The court has also directed the state pollution control board to shut down hotels, industries and ashrams that discharge untreated waste into the river. This is expected to affect over 700 hotels in the tourist areas of Haridwar and Rishikesh alone.

These rulings indicate that the court will strictly monitor polluting of the Ganges. The response of the government, however, is yet to be seen.

The ruling could be a powerful tool in the fight to save the Ganges from pollution

It may no longer be required to prove in court that polluting the Ganges actually harms humans

Some aspects of this ruling are still unclear, though. What does a right to life mean for a river or a water body? If it means the right to flow freely, what happens to dams across the Ganges?

Enforceability is another issue. Will this ruling be restricted to only the state of Uttarakhand or will it be extended across India?

The legal guardians appointed are members of the government. Will they have the independence to appeal against governmental actions like unsustainable canal dredging? Can a citizen bring a case representing a water body?

If yes, this can become a powerful legal tool in the hands of communities and activists to safeguard the environment.

Cultural context

While radically new from a legal perspective, the case has also been about recognising the traditional Hindu view that regards the universe as a manifestation of the divine.

This means that rivers, plants, animals and even the earth are considered sentient divinities with particular forms, qualities and characteristics.

Millions of people across India depend on the Ganges for their livelihoods

Hindus come from across India to bathe in the waters of the Ganges

Personification as a deity cultivates empathy and creates a strong emotional bond with the ecosystem, leading to social norms emphasising conservation. This principle of sacredness and respect has been passed down through the generations through stories and local bio-cultural traditions.

In Hinduism, the Ganges is revered as a goddess who purifies a person of all sins. The river is worshipped as "Ganga Mata", the divine mother who has sustained life and nurtured civilisation for thousands of years.

Expressions of her worship include the Ganga Aarti, where thousands offer lit lamps to the river every evening, and the Kumbh Mela, a pilgrimage of over 100 million people.

Can this view that considers rivers, trees and animals sacred, personifies them as deities and reveres them through bio-cultural traditions hold possibilities for sustainability in India? Evidence seems to suggest so.

The most famous case is the "Chipko" movement of the 1970s where tribal women hugged trees to prevent the felling of their sacred groves.

And recently, the north-eastern state of Sikkim became India's first fully organic state in just 10 years, as people saw organic farming as taking their traditional way forward.

In the case of the Ganges, the organisers of the Ganga Aarti use the occasion to raise awareness about actions that pollute the river and administer a pledge to keep it clean to thousands every day.

When environmental conservation is seen to be in alignment with the cultural context, it drives community involvement. The High Court's judgement is a welcome step in that direction.

Shyam Krishnakumar is a Research Associate with Vision India Foundation and a member of Anaadi Foundation. His work focuses on civilisational studies.

- Published21 March 2017

- Published30 August 2016

- Published12 May 2016

- Published20 January 2016