The 'studious' 12-year-old victim of India's Kashmir problem

- Published

Faizan was one of eight people killed during last Sunday's violence

The day 12-year-old Faizan Fayaz Dar died, he woke up in the morning in his hilltop home in Budgam in Indian-administered Kashmir, had a cup of salted tea, recited the Koran and pottered around in the kitchen where his mother prepared breakfast for the family.

His grandmother offered him a plate of grapes, but she doesn't remember whether Faizan had it. The son of a farmer then put on his pheran, the woollen cape-like garment Kashmiris wear, and quietly left for his Sunday lessons.

A few hours later, Faizan lay dead near a sun-baked school playground, ringed by bare walnut and willow trees. Paramilitary soldiers, eyewitnesses alleged, had shot him in the back of his head.

Carrying a packet of biscuits, he was returning home on a bright, nippy morning when he encountered a throng of local people protesting against Indian rule near the school, where polling was taking place for a parliamentary by-election.

Eyewitnesses say four shots rang out of the single-storey, squat school building which, according to some reports, was being pelted with stones thrown by protesters from a hill above and from the road in front.

Faizan possibly halted to find out what the commotion was all about, and was hit by a bullet. Two neighbours ran up to his home to deliver the news. His mother had sprinted down to the playground, hugged her bleeding son and let others take him to hospital.

"I knew he was gone," Zarifa told me.

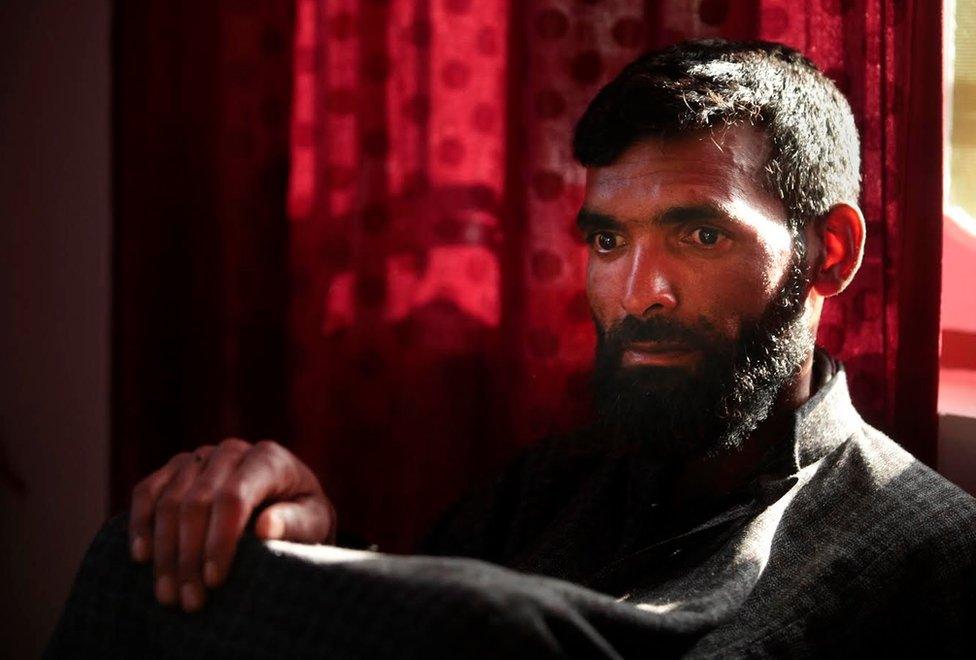

Faizan lived with his mother and father - seen here - in Budgam in Indian-administered Kashmir,

A heart-wrenching video recorded by a villager on his mobile phone minutes after the killing shows a wailing man cradling the dead boy, blood streaming down his broken face, in a packed vehicle taking him to the nearest hospital. There, the doctors declared him dead.

Faizan's final journey is recorded on another mobile phone video: his slight frame, draped in white, bobbing slightly on a hospital cot, carried through a sea of weeping, agitated mourners extolling their latest "martyr". By late afternoon, his body was lowered into the grave near his village, Dalwan.

Faizan was among the eight people killed on Sunday when paramilitary soldiers fired bullets and shotgun pellets at those protesting against Indian rule at polling centres near Srinagar, the summer capital. Election authorities say some 170 people, including 100 security personnel, were injured in about 200 incidents of stone pelting and violent protests on the day.

Five things to know about Kashmir

India and Pakistan have disputed the territory for nearly 70 years - since independence from Britain

Both countries claim the whole territory but control only parts of it

Two out of three wars fought between India and Pakistan centred on Kashmir

Since 1989 there has been an armed revolt in the Muslim-majority region against rule by India

High unemployment and complaints of heavy-handed tactics by security forces battling street protesters and fighting insurgents have aggravated the problem

The voter turnout in Sunday's election was an abysmal 7.1% - the lowest in decades - and came as a huge setback for the region's mainstream parties.

The soldiers had been brought in from other states to secure polling stations and may have been unprepared to deal with "protests and provocation" in a complex conflict zone like Kashmir, a senior official told me.

One report, external said the police had registered complaints against the paramilitary forces for firing into the crowds.

Separatist groups had rejected the elections and urged voters to boycott Sunday's poll, which took place after a politician resigned over what he described as the "anti-people" agenda of the Indian government.

Disillusioned voters - even in relatively peaceful places like Dalwan where people turned out to cast their votes enthusiastically in previous elections - generally stayed away.

Why Faizan was killed on a day when local voters rejected the ballot is not clear.

By all accounts, he was not pelting stones or hurling abuse at the soldiers. One report said police fired tear gas shells to keep the protesters away from the empty polling station, but the soldiers opened fire.

Whatever it is, Faizan became another grisly statistic in Kashmir's unending tragedy.

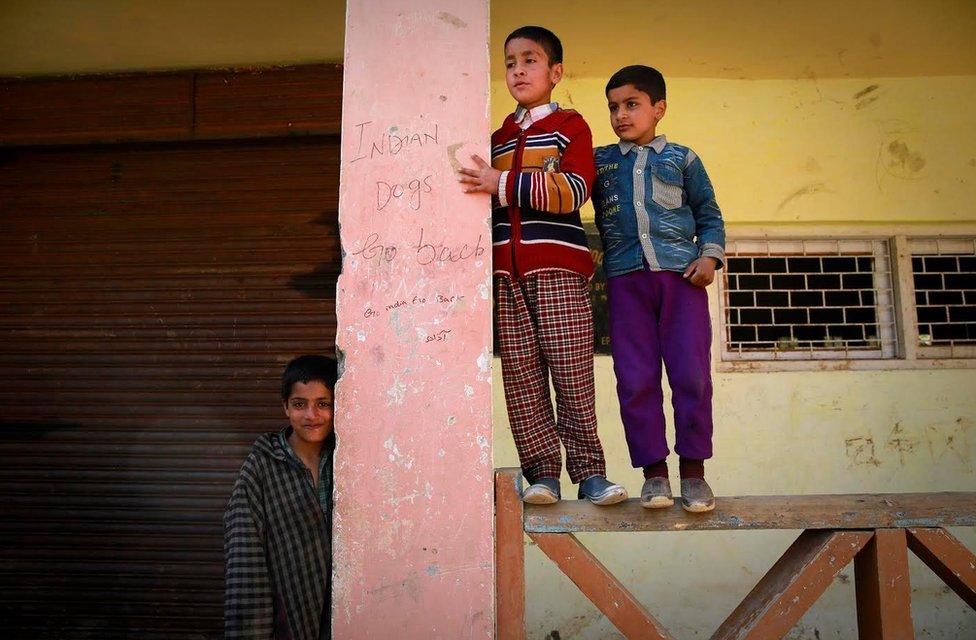

Faizan was shot near this school playground

Children stand next to anti-India graffiti on the school wall

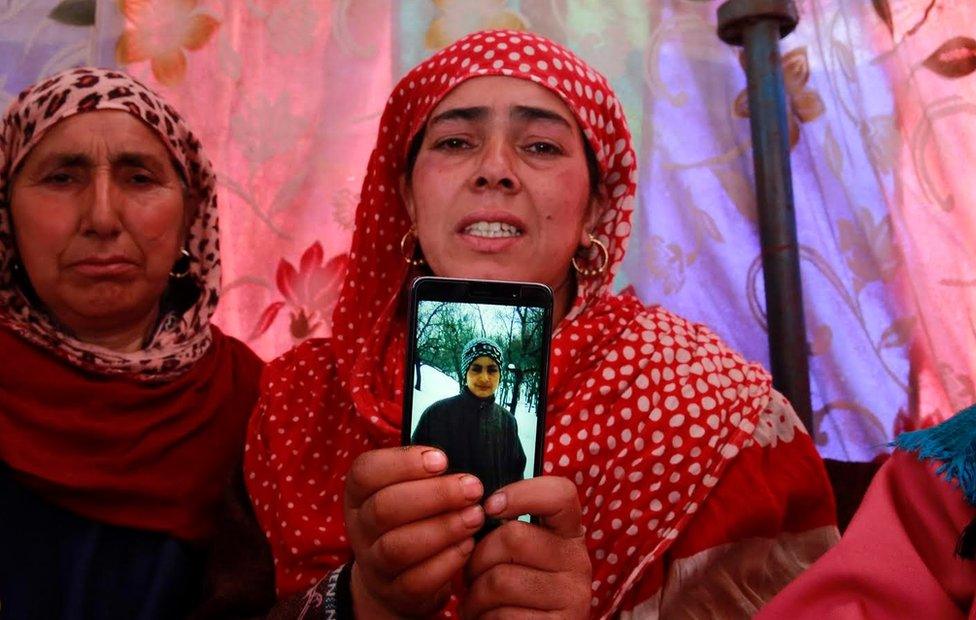

A picture taken by his friend on his mobile phone during their winter break shows the shy-looking boy - "he would often top his class, and he was very knowledgeable about the world," the friend said - clad in a woollen cap and collared jacket, peering uneasily into the camera.

"He was quiet and studious, he was doing well in school. He played cricket, and counted [former Indian captain] MS Dhoni as his favourite cricketer. He wanted to become a doctor," a cousin told me, when I visited the family.

Grief is the price one pays for love. Zarifa's lament for her dead son filled the still air inside a tent outside their home where local women had gathered to mourn.

"My son, my son, where will I find you now?" she cried, again and again.

Then she stepped out of the tent, entered her home and joined her husband in a dank, cold room. He sat there, stoic and numb, surrounded by mourners, and gazed vacantly at the pastel pink walls. The room had a red carpet and red window curtains.

"The blood of a martyr never goes waste," said Fayaz Ahmad Dar. "One day, the blood of innocents will help us gain our freedom [from Indian rule]."

Many young men said they had thrown stones at Indian forces

A brief silence followed. Zarifa broke it, bemoaning the loss of her boy.

"I am looking at your books, I am looking at your school bags. How will I touch your books again, my son? Everybody would talk about your intelligence, how you would answer every question with so much wit."

Outside the secondary school - Enter to learn, Leave to serve, its motto, is engraved on the walls - a group of young men gathered later in the day. Their eyes seethed in anger. They spoke about frustration, alienation, desperation, humiliation and hopelessness.

They said they had lost their fear of life. They insisted that they helped rebels because "they are our brothers and don't kill civilians" and are "fighting for freedom".

More than half of them raised their hands when asked whether they had pelted stones at Indian forces.

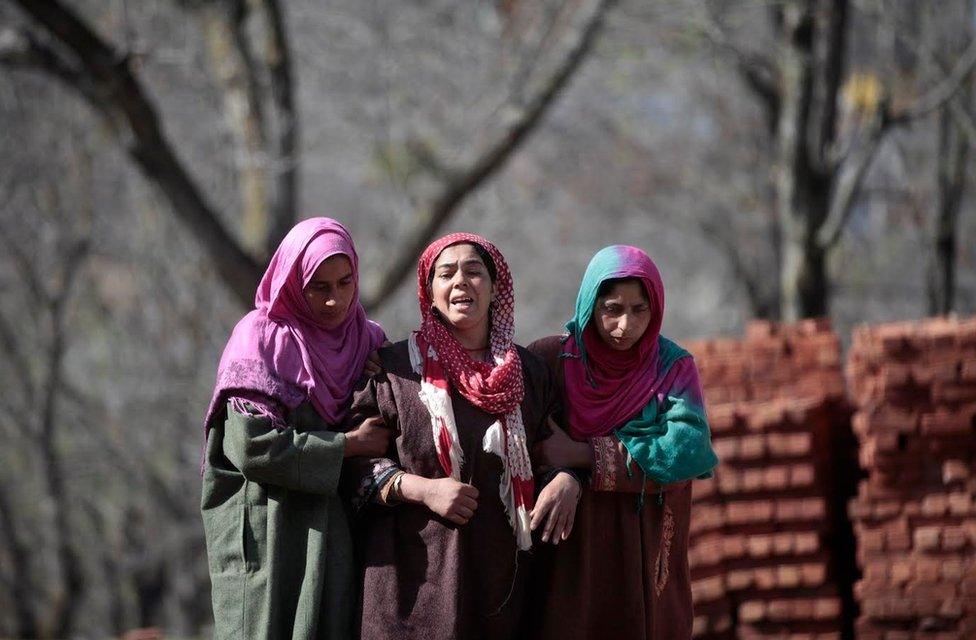

Mother Zarifa (in the centre) is mourning the loss of her 12-year-old son

"We are not safe in our own homes, we are not safe on streets. They are killing little boys now. Life is uncertain," said Feroze Ali, a school clerk.

Since February alone, some two dozen civilians have been killed during gunfights between armed rebels and security forces. The security forces have accused civilians of helping rebels escape.

The army says it has tried to reach out and engage with civilians through its 29 schools, youth clubs and cricket tournaments.

Recently some 19,000 Kashmiri young men applied for a few hundred vacancies in the army.

"Provocation and panic can lead to accidents. Security forces often fire when they face life threatening situations. But protecting civilians remains our first priority in this situation. When a civilian dies, it hurts us," an army officer told me.

The region has seen heightened tension and increased unrest since July when influential militant Burhan Wani was killed by Indian forces. More than 100 civilians lost their lives in clashes with the security forces during a four-month-long lockdown, including a 55-day-curfew, in the restive Muslim-majority valley.

Clashes between security forces and stone pelters in Kashmir have become routine

Young men are angry in a region where 40% have no jobs

Kashmir, clearly, appears to be teetering on the brink of an open public revolt against Indian rule.

Many say the federal government's near-complete lack of engagement and dialogue with local stakeholders and Pakistan, a complete mistrust of the local government and a lack of development and jobs have left most people jittery and alienated.

Militancy continues to be at low ebb - there are an estimated 250 militants in the state now of which 150 are local - compared to several thousand during the peak of insurgency in the 1990s.

But young Kashmiris - more than 60% of the men in the valley are under 30, and more than 40% of men in Kashmir are jobless - are restless and angry. The local political parties are in danger of "becoming irrelevant", as a leader of an opposition party told me.

"This is the worst situation that I have seen. Earlier, it was a movement led by the militants. Now it is being led by the people," says Feroze Ali, 35, a schoolteacher.

"India needs to be worried, very worried about this."