Counting the dead in Manipur's shoot-to-kill war

- Published

Police commando Herojit has admitted to more than 100 unlawful killings. Warning: This video contains distressing images

More than 1,500 people were allegedly killed in a wave of extra-judicial executions by security forces in India's insurgency-ridden north-eastern Manipur state between 1979 and 2012. Last year, in a landmark ruling, the Supreme Court asked relatives of the victims and activists to collect information on the killings. The court will rule in July whether to order an official investigation which could lead to convictions. Soutik Biswas travelled to Manipur to find out more.

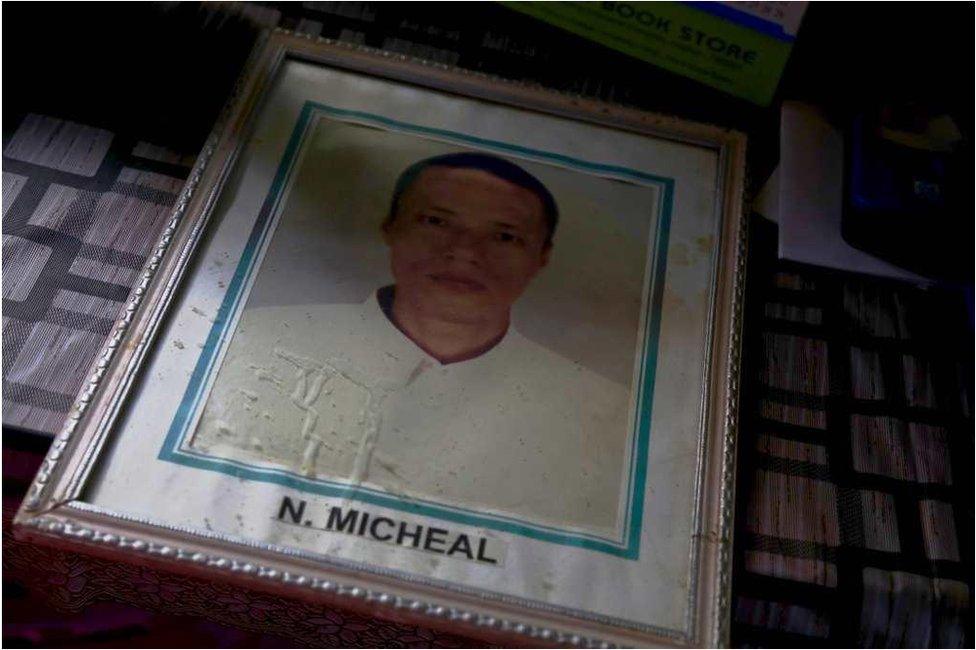

Neena Ningombam vividly remembers the day her husband disappeared - and ended up a corpse on cable news.

It was a bright, sunny November day in 2008, and 32-year-old Michael was visiting a friend's house in Imphal, the non-descript, mountain-ringed valley capital of Manipur.

At home, Ms Ningombam was doing her chores. Her two boys were fast asleep. At half past three in the afternoon, her mobile phone rang.

Michael was on the line saying that he had been picked up by police commandos on his way home, and that she should quickly pass on the news of his arrest to a senior policeman who was known to the family so that he could help secure his release.

The call disconnected abruptly. Two hours later, a man finally picked up the phone and told Ms Ningombam that her husband was "in the toilet". He said he would inform him that she had called.

Michael never called. When she tried calling again, his phone was switched off.

Tense and confused, Ms Ningombam sat down in front of the TV. Her sister-in-law had gone in search of the police officer known to the family, but he couldn't be found.

Manipur: Insurgent hotspot

Manipur, a hilly north-eastern state on the border with Myanmar (Burma), has been a cauldron of insurgency for more than four decades.

At one point, the state was home to some 30 armed groups. Six main groups are outlawed.

The violence is stoked by ethnic rivalries, and demands for independence and affirmative action for local tribespeople. Some rebel groups also act as social watchdogs, targeting liquor sellers, drug traffickers and banning Bollywood films. Lack of jobs has worsened matters.

According to the government, 1,214 civilians were killed by insurgents between 2000 and October 2012. Also, 365 police and soldiers were killed by insurgents during the same period.

A controversial anti-insurgent law, the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (Afspa) - which protects security forces who may kill a civilian by mistake or in unavoidable circumstances - has been in effect here since 1958 and been partly blamed for the "perpetual immunity" enjoyed by the forces.

In July 2016, the Supreme Court remarked that the law could not be an excuse for retaliatory killings and excesses.

So she waited, and waited, for Michael, watching the news on a local channel. At nine in the evening, the screen exploded with breaking news.

They were showing footage of her bloodied husband, wearing blue nylon tracksuit bottoms and a dark green T-shirt, lying dead on a stone floor. A Chinese-made grenade lay next to the body. The news reader breathlessly announced that police commandos had killed another militant.

Ms Ningombam says she looked at the screen and froze. Grief felt so like fear itself.

"I just remember that I cried and cried and cried. Someone came rushing in and yanked off the TV cable wire. My brother-in-law went to the morgue and identified him."

The police defended the killing of Michael Ningombam

The post-mortem report said Michael Ningombam had died of "shock and haemorrhage as a result of firearm injuries to lungs and liver".

The police said Michael and two friends were riding a motorcycle when they were stopped by half a dozen vehicle-borne commandos in a wooded area on the outskirts of the city. The pillion rider was said to have fired at the vehicle and Michael apparently tried to throw a grenade at the commandos who then shot and killed him in an act of self-defence. The police also said Michael was a militant and extortionist.

"My husband was struggling, doing odd jobs. He was a drug user and he was trying to kick the habit. But he was not a militant," Ms Ningombam , 40, told me. They had met in college, fallen in love, eloped and married.

The neighbourhood had erupted in protests after the killing, demanding an investigation.

Ms Ningombam, who holds a masters degree in history, took up a driving school job to support her sons. She also single-handedly launched an arduous battle for justice, filing official complaints, petitioning the government and the court, collecting papers and coaxing a key potential witness to testify.

Every day, for more than a month, she would drive 15km (9 miles) on her scooter to the wooded city outskirts where an ageing shop-owner had spotted the commandos drive by in a SUV with her husband on the afternoon of the killing. Then he had heard the sound of gunfire in the distance.

"After days of coaxing him and interacting with his family, the old man consented to testify and became a key witness. That is how we sometimes get some justice in Manipur. The state doesn't help you," she said.

Kamalini Ngangban's son Naoba was killed outside the family home in 2009

Four years later, in July 2012, the district judge, in a report, concluded on the basis of evidence that Michael had been killed by Manipur police commandos and that there had "been no exchange of fire" between the policemen and the victim.

The high court accepted the report, and ordered that 500,000 rupees ($7,759; £6,115) should be paid in compensation to Ms Ningombam.

Michael Ningombam was not alone in meeting such a fate. Rights groups believe as many as 1,528 people were unlawfully executed - also known as fake encounters - in Manipur between 1979 and 2012.

The overwhelming majority of the victims were men, many of them lower income and unemployed. Among those killed were 98 minors and 31 women. The oldest was an 82-year-old woman; the youngest, a 14-year-old girl.

'Climate of impunity'

The most well-known victim was Thangjam Manorama Devi, 32, who was allegedly gang raped and murdered by paramilitary soldiers in 2004, provoking a unique nude protest by mothers and grandmothers that stunned the world.

Some of the killings have been investigated by a federal human rights organisation. Judicial inquiries have resulted in compensation for a few hundred victims' families. But what is unsettling is that not a single policeman or soldier has been put on trial in connection with the killings.

"People have been picked up, called insurgents and killed. The climate of impunity means the police often don't register cases. You have to fix accountability. You cannot just suspend the right to live and kill people," says Babloo Loitongbam, a prominent human rights activist.

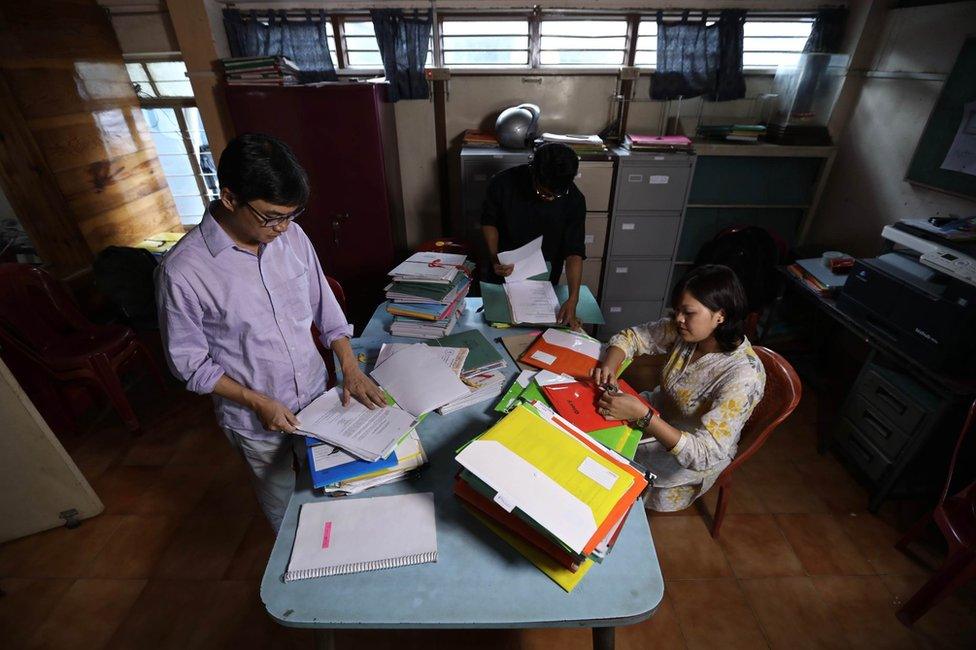

Eight years ago, the families of the victims joined hands with activists to do something about this "culture of impunity enjoyed by the police, army and paramilitaries". On a July morning in 2009, they gathered in a room in Imphal, shared their stories and starkly christened themselves the Extrajudicial Execution Victim Families Association.

The Extra Judicial Victim Families Association works out of a single-room office in Imphal

Last July, responding to a petition filed by the families, the Supreme Court, in a landmark judgement, external, asked the petitioners to collect more information about the alleged murders. Even if the investigations revealed that the victim was an "enemy and an unprovoked aggressor", the judges said, it had to be determined whether "excessive or retaliatory force was used to kill the enemy".

So the newly empowered civilian "investigators" put out adverts and appeals in the local media, and began gathering information - and potential evidence - on the killings.

Some 900 families responded, bringing with them police complaints, post-mortem reports, funeral records and court orders related to killings. Volunteers - students, relatives of victims - spread out to each of the nine districts of the hilly state, collecting information. A local lawyer, working pro bono, helped with the legal work.

A year later, a dozen grey filing cabinets in the office were overflowing with more than 1,500 files, each devoted to a killing. In April, the victims handed over details of 748 killings to the court even as they worked on other cases. Sometime this month, the top court is expected to rule on investigating these cases.

Banal horror

The banal horror of death in Manipur is possibly unequalled in India. "It takes us a long time to raise our children. Then, when they grow up, they are shot. This cannot go on. We no longer want to look for our children in the morgue," a women's rights activist in the state once said.

There have been countrywide protests against the alleged killings in Manipur

Men disappeared or were picked up by security forces while going to the market to buy fertiliser for their farms, parts for cars, to rent a DVD or while waiting for a passenger bus. Others were killed on their way to meet girlfriends, while fishing in a lake, or simply having food in a restaurant. A woman was shot while she was feeding her baby girl.

Sometimes, security forces would simply break into homes, drag out suspects in front of their families and kill them.

That is what happened to Ngangban Naoba Singh, a 29-year-old theology student, on a still summer night in May 2009.

Naoba had returned home with his sister from a wedding late in the evening. The two were watching a film on TV, when their mother, Kamalini Ngangban, a retired census worker, joined her children.

"These late-night movies are not meant for elders. Go to sleep," Naoba joked.

Those were his last words.

Around midnight, Ms Ngangban woke up to "violent knocking on the door". Then she heard voices. Some people were trying to enter the house.

She rushed to her son's bedroom and woke him up, and tried to take him out of the back door. Did she think that they had coming looking for her son?

"I knew something was wrong. Naoba was so sleepy, I don't think he realised what was going on.

"The moment we stepped out of the back door, someone stopped us."

She saw silhouettes in the moonlight. She thought she saw 10 of them.

'Stop him!'

One man shouted at Naoba: "Where are you going?" He said his mother had asked him to come out.

Things quickly spiralled out of control in the dark.

The men "took away" Naoba, his parents were pushed back into the house, their phones were removed and the doors bolted from outside.

There was an exchange of words, some orders were barked out, and then shots rang out in the darkness.

"Stop him! Stop him!" somebody screamed. A vehicle was starting up behind the house.

Ms Ngangban hoped her son had managed to run away. It was pitch dark, and the family was confined inside the house for the rest of the night. When dawn broke, they found out that her son had been killed in their backyard and his body taken away in a vehicle.

More than 1,500 people have been allegedly executed unlawfully in Manipur

"Even today, I don't know why he was murdered. I want to know the truth. If we did something wrong and tried to escape, they could have shot him in the leg," she says.

"You know, he was my favourite son. We used to go to the theatre together. My two other children live and work outside Manipur. Naoba was supposed to be the man of the house."

The police said they had cordoned off the house that night to search for Naoba, who they said was a member of an outlawed rebel group and an extortionist.

Three years later, a judicial inquiry report ruled there was no evidence to show he was either.

The judge ruled the police commandos had fired "indiscriminately without any attempt to arrest Naoba by following the rule of law prevailing in this democratic country". The Supreme Court is now hearing the case, and is to decide on compensating the family.

Staying at home was no guarantee that your life was secure. Oinam Amina Devi, for example, was shot by paramilitary soldiers while she was feeding her one-month-old baby girl in her house in April 1996.

The soldiers had chased a suspected rebel who had run into her tin-roof village home and hidden under the bed. Amina, who was on the veranda, panicked and ran inside with her baby when she saw the soldiers running in. When she tried to shut the door, the soldiers opened fire. A bullet pierced her and exited, then entered her baby.

'Unprovoked killing'

The bleeding daughter was taken to hospital where surgeons removed the bullet. Her mother died instantly.

There were demonstrations in the area and the family refused to accept Amina's body after the post mortem. Her corpse was taken back to the police station and later cremated. Under pressure, the government announced an inquiry.

The investigation concluded that the firing was "unprovoked, unwarranted and indiscriminate". The government submitted the report to the Supreme Court and the family received a compensation of 50,000 rupees.

Today, the daughter, Oinam Sunita Devi, 20, lives with her father who married again.

"I cannot explain my sadness. I miss my mother and I sometimes wonder how I survived. This is my fate," she says.

Oinam Sunita Devi (right) was hit by a bullet fired by soldiers which killed her mother and now lives with her father (left)

The police and security forces have, for the most part, maintained that the encounters are genuine and the victims were militants killed in counter-insurgency or anti-terror operations.

The government told the top court last year that some "5,000 militants were holding some 2.3 million people of Manipur to ransom and keeping people in constant fear". It said 365 police and paramilitaries had been killed by the rebels between 2000 and October 2012.

But things have become murkier after a police commando Herojit Singh admitted to journalists in January last year that he had shot dead an unarmed, suspected rebel, external inside a bustling Imphal market in 2009. In a chilling interview, external in July he admitted to killing more than 100 people and that he kept a "tally of his kills" in notebooks.

When I met him last month in a hotel room in the city, the 36-year-old policeman, son of a government worker, said he was battling depression. He said he hadn't slept at all at night for two years. He had also survived a road accident in the city; many feel someone may have tried to kill him as he had made too many enemies.

'No remorse'

When I asked him how many people he had killed, he said: "I don't remember the details."

"Was it more than 100 people?" I asked.

"Yes."

He said he felt no remorse for the killings, and he was ready to face any punishment.

"I was simply doing my duty and following the orders of my seniors. I confessed because I thought it was important to tell the truth," he said.

Life has been difficult after his confession. Detectives from the federal Central Bureau of Investigation are investigating the killing of 23-year-old Chungkham Sanjit in the market and questioned the commando more than 10 times. Herojit Singh has been suspended a number of times for "indiscipline and grave misconduct", and then reinstated.

By day, he spends time with his children, helping them with their homework. When his pet chicken fell ill recently, he says he panicked, clasped it to his chest and ran with it to the vet.

Leitanthem Priya Leika's husband Premananda was killed on his way to the market to buy timber in 2006

Nights are brutal. "I dread nights. I wish I had my own sun, which I could put in the sky and there would never be any darkness," he says.

Yumnam Joykumar Singh, the former chief of Manipur police, and now the deputy chief minister of a newly-elected government ruling the state, says Herojit Singh is exaggerating his role in the killings.

"He's bluffing. He was possibly involved in 10-15 encounters. But he's claiming he has killed so many people. Let the courts ask him how many cases he was present in."

Mr Singh, who earned a reputation for being a firm and unyielding policeman, says rights groups are exaggerating the number of fake encounters.

'Fire your weapon'

"There might have been a few cases [of] extra-judicial killings, but I don't think the numbers being quoted are that many. If 1,500 people had been killed illegally, there would have been more protests in the state," he told me.

During his time as the chief of police, Mr Singh beefed up the force - from 20,000 to 34,000 policemen - and made it "the leading force" to fight insurgents. He said militancy and extortion had led to a near-collapse of public order in the state, and he told his policemen: "If you have a weapon, you can fire back."

"That is how we fought the insurgency."

Bringing up the dead is not easy. Memories fade. Potential evidence - post mortem reports, police complaints - yellow and crumble with age. Hope waxes and wanes. Time heals wounds, but also allows for reflection, and gives you renewed purpose.

So, emboldened by the Supreme Court's intervention, the families of victims in Manipur have plunged into an unexpectedly fierce fight for justice, in many cases years after they lost their loved ones. The killings have stopped, but there have been no punishments for the crimes yet.

The families have stirred with a newly-found collective courage, not because they have great hope in an egregious and slow-moving criminal justice system.

Many say they don't want their children and families to be permanently tainted by fake allegations about their fathers, brothers, sons, daughters and wives. They know the crimes and misdemeanours of a family member can easily taint all born within it.

"I kept fighting because of my sons. I don't want people to call them children of a militant. I had to clear my dead husband's name to protect them," says Ms Neena Nongmaithem.

"And, yes, the dead should not be completely forgotten."

Pictures by Varun Nayar and Karen Dias