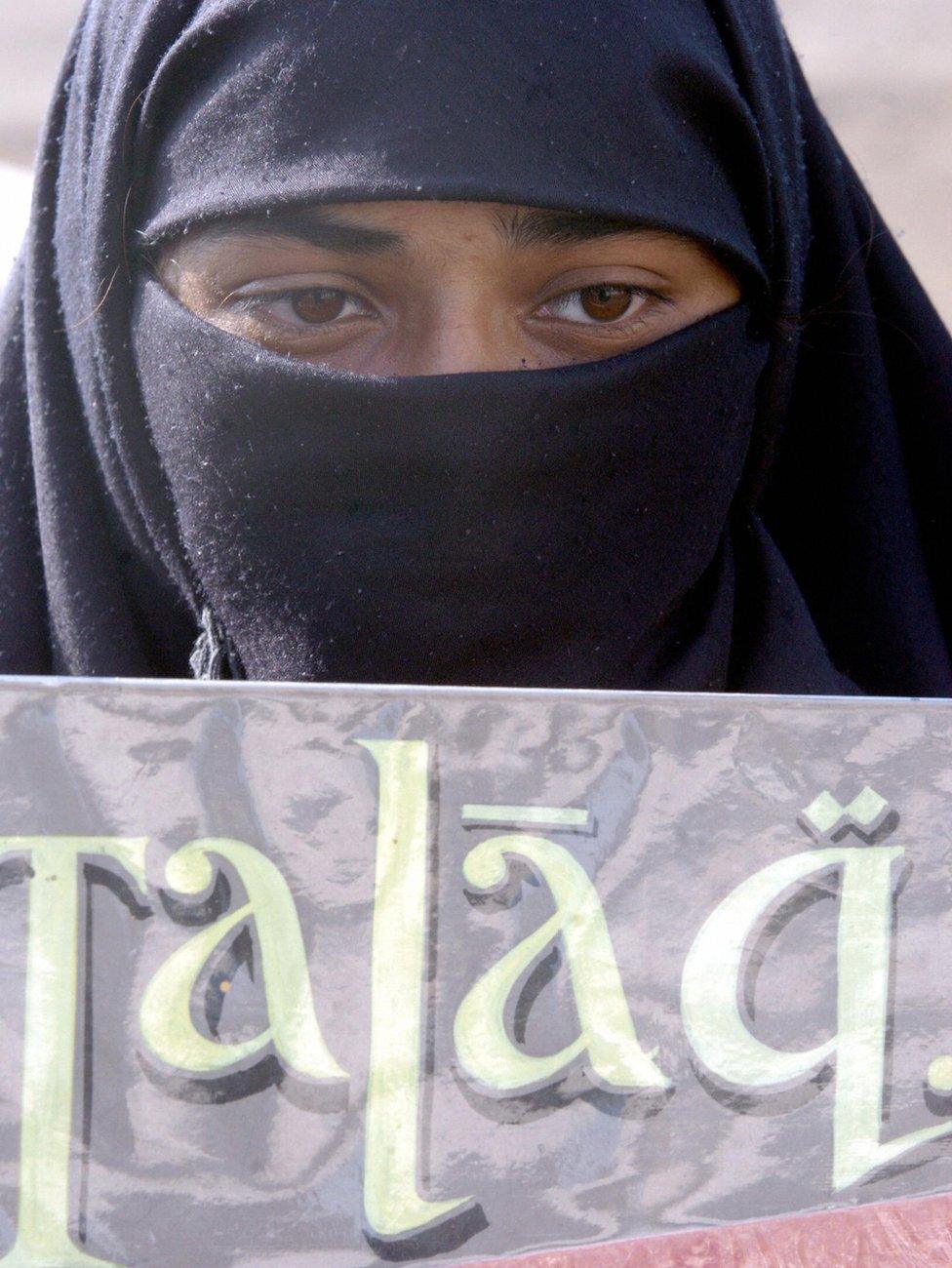

Triple talaq: How Indian Muslim women fought, and won, the divorce battle

- Published

The Indian Supreme Court has ruled that the controversial practice of instant divorce in Islam is unconstitutional. It is being hailed as a huge victory by rights activists. But the battle was not easy, as the BBC's Geeta Pandey in Delhi explains.

Over the years, Muslim women in India have complained of living in perpetual fear of being thrown out of their matrimonial homes in a matter of seconds because a Muslim man, if he chooses, can end years of marriage just by saying the word "talaq" (divorce) three times.

A campaign to end the practice of unilateral instant "triple talaq" began in India several decades ago.

But it picked up steam last year when a 35-year-old mother-of-two approached the Supreme Court seeking justice.

Shayara Bano's petition, filed in February 2016, said she was visiting her parents' home in the northern state of Uttarakhand for medical treatment when she received her so-called talaqnama - a letter from her husband telling her that he was divorcing her.

Her attempts to reach her husband of 15 years, who lives in the city of Allahabad, were unsuccessful. She was also denied access to her children.

In her petition, she demanded a total ban on the practice saying it allowed Muslim men to treat their wives like "chattels".

She also asked the court to outlaw halala (where a divorced woman has to marry another man and consummate her marriage in order to go back to her former husband) and polygamy (Muslims in India are allowed to take four wives).

These practices were "illegal, unconstitutional, discriminatory and against the modern principles of gender justice", she said.

Divorce in Islam

Islamic scholars say the Koran clearly spells out how to issue a divorce - it has to be spread over three months which allows a couple time for reflection and reconciliation.

But for centuries now, the controversial instant triple talaq - known as Talaq-e-Bidat - has been practised in India with approval from the clergy.

Bidat is the Persian word for "sin" and it allows Muslim men to divorce their wives by just saying "talaq talaq talaq".

Campaigners say modern technology has made it even easier for unscrupulous men to dump their wives by phone, email or text.

There have also been instances where men have used Skype, WhatsApp or Facebook for the purpose.

The unilateral, instantaneous triple talaq finds no mention in Sharia or the Koran and it's already banned in 22 Islamic countries, including Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Over the years, many Muslim women have challenged triple talaq in courts. So what was different about Shayara Bano's case that it became such a game-changer?

"This was the first time a Muslim woman had challenged her divorce on the ground that her fundamental rights had been violated," her lawyer Balaji Srinivasan told the BBC.

Guaranteed by the constitution, these rights are often seen as the backbone of Indian democracy and they cannot be easily altered or taken away, and a citizen can seek legal redress if they are violated.

Shayara Bano petitioned the Supreme Court to declare triple talaq unconstitutional

"The clergy told her 'you don't have fundamental rights because of your faith'. So in India, if you're a Hindu woman or a Christian woman or a woman from any other faith, you are alright. But if you're a Muslim woman, you have no fundamental rights?

"So Shayara Bano approached the court, saying her constitutional right to equality had been violated and the top court took up her case," Mr Srinivasan said.

"I wonder why no-one thought of this before," he says, adding, "maybe, it's an idea whose time has come."

What also helped was the very vocal campaign against the practice by the Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan (BMMA - Indian Muslim Women's Movement) over the past few years.

"It's nothing but patriarchy masquerading as religion," says Zakia Soman, one of the founder members of the BMMA. "Who gave the law board the right to take away our rights given to us by Allah?"

Activists have long campaigned for a total ban on triple talaq

In 2007, the organisation started compiling a list of women facing instant divorce and polygamy.

"We did a survey of 4,710 women and of the 525 who were divorced, 414 [or 78%] had been divorced through instant triple talaq," Ms Soman says.

The organisation released a report chronicling nearly 100 cases where women were left destitute with nowhere to go.

In December 2012, they held a public hearing on the issue, attended by 500 women from across the country.

They wrote letters to the prime minister, the law minister, the minorities' affairs minister and the women and child development minster.

They collected 50,000 signatures, calling for a ban on triple talaq.

Two months after Shayara Bano's petition was filed, another woman Aafreen Rahman challenged her divorce in the Supreme Court. Over the following weeks, three other women and two women's organisations, including the BMMA, filed similar writs in the top court.

The cases were clubbed together and the court set up a multi-faith bench made up of five judges - a Hindu, a Sikh, a Christian, a Zoroastrian and one Muslim - to consider the matter.

The bench, headed by Chief Justice JS Khehar, heard the case for six days from 11 May and the two sides were given equal time to present their views.

Thousands of lives have been ruined by instant divorce

The influential All India Muslim Personal Law Board, which was among those opposing the ban, claimed that the practice had been around for more than 1,400 years and argued that "though sinful, triple talaq is a matter of faith for Muslims".

If men were unable to divorce their wives, the board said, they "may resort to illegal, criminal ways of murdering or burning her alive".

Its lawyers also said that India's Bharatiya Janata Party government had a Hindu nationalist agenda and that Muslim personal law, customs and practices were under threat.

The board promised, external that it would work to discourage the practice and those who resorted to instant divorce would be boycotted by the community - an idea that was strongly opposed by lawyer Indira Jaising who represented one of the petitioners, an organisation of Muslim women called the Bebaak Collective.

"One illegality over another, social boycott is illegal, hope the court is not carried away by extra constitutional solutions to triple talaq," she tweeted. Ms Jaising also wrote about "the patriarchy felt, seen, and heard in court during the hearing".

Accusations of misogyny and injustice also seemed to worry the judges, external who repeatedly asked if instant divorce was bad in theology, how could it be good in law?

"You pray in the mosque every Friday. In that prayer, you say triple talaq is a sin and bad. How can you then say it is an integral part of Islam?" Chief Justice Khehar wondered.

Justice Kurian Joseph added: "Can something found to be sinful by God be validated by men through law?"

In the end, the court did not accept the argument that just because it had been custom for 1,400 years, it should still be acceptable.

With Tuesday's order, India finally has an answer to this key question - instant divorce is no longer just sinful, it's also illegal.