Indian mutiny: Remembering farmers who fought British rule

- Published

Indian soldiers of the British Army revolted against the Raj in 1857

Indian soldiers, known as sepoys, set off a rebellion against the British rule in 1857, often referred to as the first war of independence. Ordinary farmers took up arms to support them in the fight against the British, but their contribution has been largely forgotten. A group of researchers is now trying to revive their memory, writes Sunaina Kumar.

The village of Bijraul, on the outskirts of Meerut district in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, had a small celebration on 10 May to mark the 160th anniversary of the uprising of 1857 - a rebellion against the rule of the British East India Company.

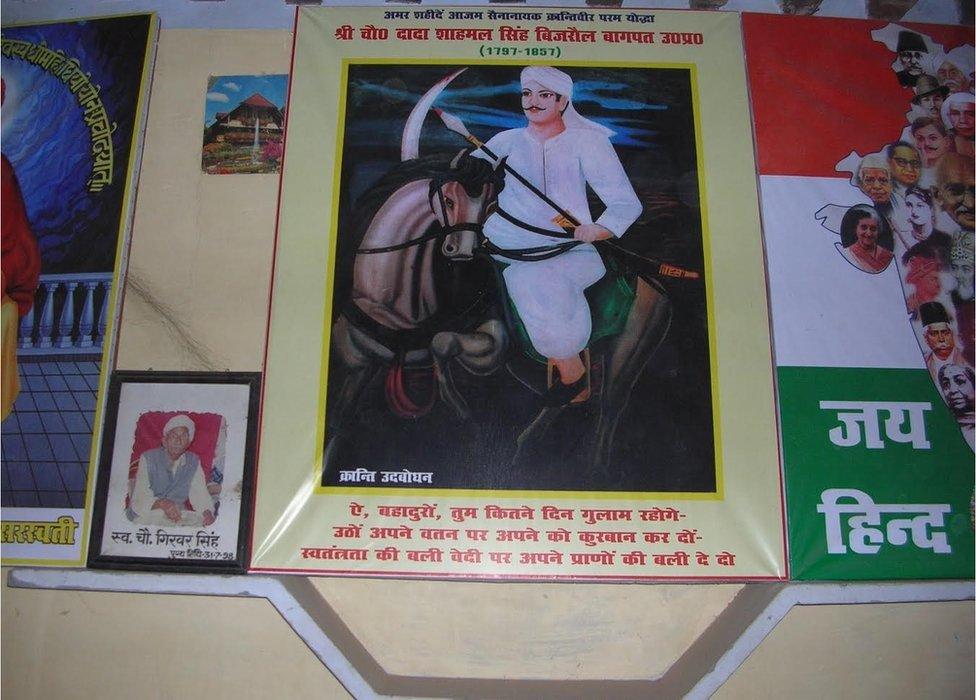

The residents of the village paid tributes to their ancestor Shah Mal for his role in the revolt. He inspired thousands of peasants across nearly 84 villages to leave their fields and take up arms in 1857.

But not many people in India have heard of this prosperous landlord.

"People of the district were in a fever of excitement to know whether 'their raj' or ours was to triumph," wrote Robert Henry Wallace Dunlop, a civil officer, in Service and Adventure with the Khakhee Resallah, a record of the volunteer corps formed to quell the uprising.

Baba Shah Mal led the mutiny in his village

Shah Mal was extraordinarily plucky. He collected and sent supplies to the mutineers of Delhi and blew up the bridge of boats on the Yamuna river, cutting off all communication between Meerut and the British headquarters in Delhi.

In July 1857, at least 3,500 peasants armed with primitive swords and spears led by Shah Mal clashed with British soldiers of the East India Company, represented by the cavalry, infantry and artillery regiments.

The landlord was killed in the battle.

The story of Shah Mal, branded an "upstart" by the British, who "from nothing became a rebel of some importance", has been subsumed into the familiar narrative of 1857 - that it was a mutiny of sepoys which spread to former rulers of northern India.

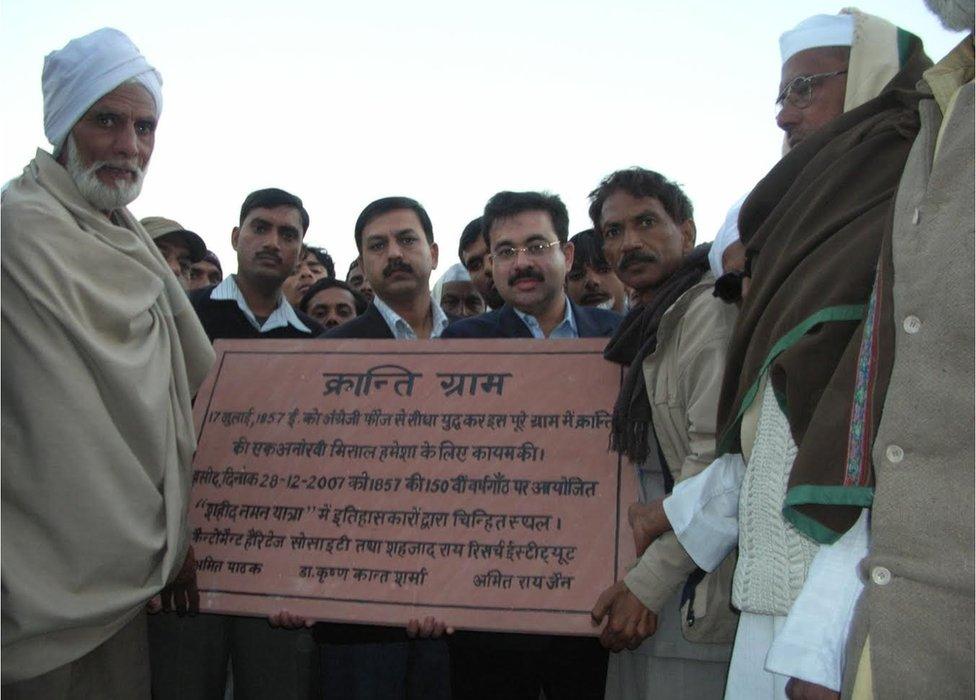

His descendants have put up a memorial stone in the village

His is one of the many forgotten accounts of peasants and commoners, who were an essential part of the rebellion, which a group of dedicated historians from Meerut are trying to revive.

An important component of the 1857 uprising were the "thousands of spontaneous peasants' jacqueries [revolt] all over northern India," writes cultural historian Sumanta Banerjee, in his book, In the Wake of Naxalbari.

"But, the role of the peasantry in the uprising has been glossed over by bourgeois historians," Mr Banerjee elaborates.

The Sikander Bagh (park) in Lucknow city was the venue for a fierce battle during the 1857 uprising

British records

Most historical accounts have dwelt on the elitist character of the insurgency. To upend this narrative, historians have only to turn to British records of the time, which are richly informative about the widespread extent of peasant participation.

Like this entry from the British records of 1858 sheds light on how the British attacked villages in Meerut.

"The principal villages were successfully surrounded, a little after daybreak, by different parties told of. A considerable number of the men were killed; 40 taken prisoners, 40 of whom were consequently hung…."

Amit Pathak, a historian and author, KK Sharma, a professor of history, and Amit Rai Jain, a researcher and historian, all from Meerut, and the founders of Culture and History Society, a non-profit association, have carefully pored over the records of the uprising to revive the memory of people like Shah Mal.

Ten years ago, on the 150th anniversary of the uprising, they started the "baagi (rebel) villages" project. The villages that the British declared as baagi were the ones that had fought for independence, and which later faced heavy reprisals when the British regained control of the territories.

After identifying such villages, the researchers meet the descendants of the rebel fighters and record their memories, passed down from one generation to another, which they corroborate and document.

A memorial gate has been made in Busodh village

"The real power of the uprising was in rural India," Mr Pathak tells the BBC.

"The tragedy we find when we visit these villages is that the descendants of the rebels are still mired in poverty."

When the uprising collapsed after the fall of Delhi, the rebels were hanged, and their lands were confiscated, auctioned off and redistributed among those who were loyal to the British.

"When we visited the village of Busodh, we were surprised to find that from a prosperous village of landlords as recorded by the British, it had turned into a poor village of landless labourers. It is one of many such instances," said Mr Pathak.

The researchers have surveyed 18 such villages so far.

But government officials seldom visit these places. In some villages, the researchers found that the families of the revolutionaries were completely ignorant about their history.

"When we go there and we recognise the contribution of their ancestors, we give them back their pride and respect, and in the countryside that is highly valued," Mr Pathak adds.

Researchers met Baba Shah Mal's family to corroborate their findings

Mr Jain says that the stories of people like Shah Mal have led to social awakening of sorts.

Pramod Kumar Dhama is the fifth-generation descendant of Gulab Singh, a peasant leader from the village of Nimbali who fought alongside Shah Mal.

Mr Dhama, 50, teaches in a school and is a repository of memories on Gulab Singh's heroics.

"As a young boy, I was told I come from a great family which had fought for the country. It inspired me to become a teacher," says Dhama.

On 18 July, the residents of Bijraul will honour the memory of those who died fighting. Shah Mal and 26 leaders who were hanged on a banyan tree close to the village will be remembered.