The people trying to fight fake news in India

- Published

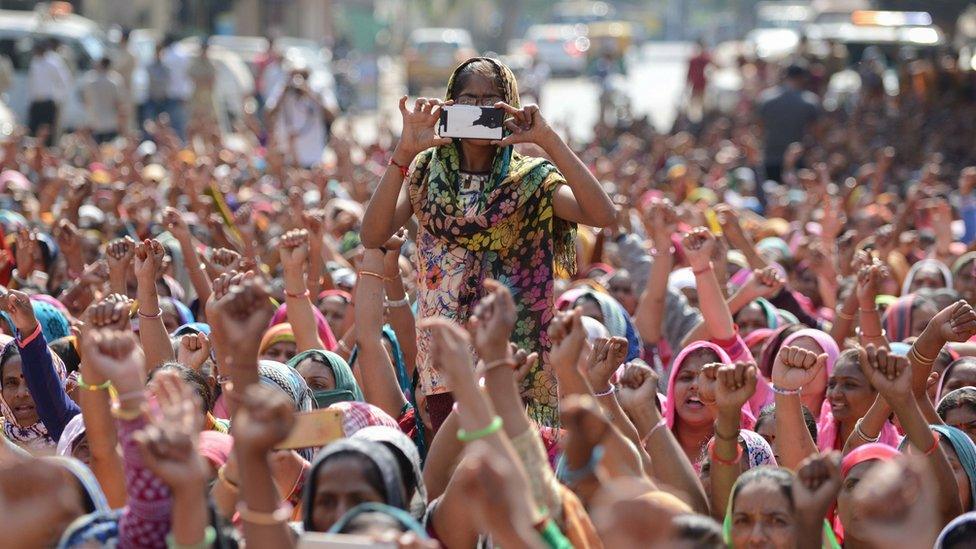

For a majority of Indians, their first point of exposure to the internet is via their phone

Earlier this year, mobs in the eastern Indian state of Jharkhand beat seven people to death in two separate incidents that horrified the country.

After the dust had settled, it transpired that the victims had been mistaken for child traffickers.

The trigger was a WhatsApp message that had gone viral, urging people to be careful of strangers as they most likely belonged to a "child lifting gang".

As the message passed on, police say hysteria increased. Villagers armed themselves and began attacking anyone they did not recognise, with tragic results.

Unlike in western countries, most of India's fake news spreads via WhatsApp and mobile phone messages, because for a majority of Indians, their first point of exposure to the internet is via their phone.

India's telecom regulatory commission says there are more than one billion active mobile phone connections in India, and millions of Indians have started getting online in a very short space of time.

"Reach has exploded, thanks to the proliferation of smartphones and cheap data packages. Rumours spread further and faster," Pratik Sinha, the founder of Altnews.in, external told the BBC. `

"Suddenly people from rural areas in particular are inundated with information and are unable to distinguish what is real from what is not. They tend to believe whatever is sent to them."

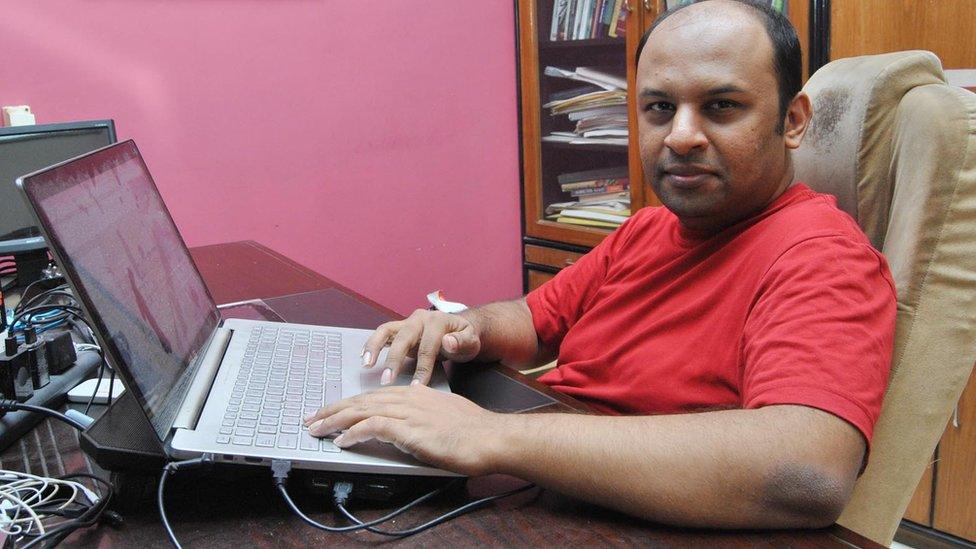

Mr Sinha is one of a handful of people trying to "fight" the scourge of fake news in India.

Formerly a software engineer, he now runs Altnews fulltime, funding it with his own savings and ad revenue.

Altnews fact checks viral stories circulating on social media and WhatsApp, verifies photographs and videos and also calls out stories by media organisations that may be based on fake news.

Stories he has debunked include a viral video claiming to show a Hindu girl being lynched by a Muslim mob. The video, Mr Sinha says, regularly does the rounds on WhatsApp with a plea to the receiver to send on the message with the hope that authorities will be pressurised into taking action.

But the video though horrific, is actually of a Guatemalan girl being beaten by a mob and is two years old.

In fact a majority of the videos, Mr Sinha has said, external, seem to be propagated by people with hardline sensibilities and many have an "anti-Muslim" slant.

Some tools to be a myth buster

The encryption technology used by WhatsApp makes it hard to track fake news propagated on the site

Google reverse image search is favoured by all of the Indian myth-busters. It allows you to upload an image online and then search for where it may have appeared in the past. You can either go to Google and do an image search or add the Google Search Image extension on to your Chrome browser.

Tineye also allows readers to check if images have been manipulated.

The free video to jpg converter transforms video into images that can then be searched separately. This can also be installed as a browser add-on.

InVid has developed a browser application that allows people to add video links into it. It then provides detailed analysis about the video in question.

Part of the challenge, he adds, is that WhatsApp, which is the main medium of fake news in India, is "like a mutating virus".

"WhatsApp has end to end encryption. What that means is every message sent between two parties has a unique set of keys, regardless of whether it is the same message being passed on. This means that when fake news happens, there is no trail. It becomes tough for even WhatsApp to track."

The other issue, according to Durga Raghunath, an Indian digital expert, is that people don't question sources on social networks or messaging apps.

"The mental approach is different. Many of the issues people see on these platforms have an emotional connect, and because the information comes to us via family and friends, the inclination to double check is very low," she told the BBC.

Pankaj Jain, the man behind verification site SM Hoax slayer, external, knows this better than most. He told the BBC that his inspiration to bust hoaxes were the "stupid rumours" he kept receiving on WhatsApp.

Pankaj Jain said he started his site because of the "stupid rumours" he kept getting

"I began by responding to messages to tell people what they were passing on was not true, and then decided to take it further."

He came to prominence after becoming one of the first people to shoot down a viral news story which claimed that India's new 2,000 rupee note was embedded with a "nano GPS chip" that allowed authorities to track it if it was taken outside the country.

"I did a lot of research and the thing that jumped out at me the most was that nano-GPS chips need a power source to function, which the new currency note very clearly did not have," he said.

His other notable "busts" include proving that a photograph tweeted out by a leading news channel purporting to be of two "terrorists" killed in Indian-administered Kashmir was actually a two-year-old photograph from Punjab, and more recently, explaining that a viral WhatsApp forward of the Indian flag flying atop the Israeli parliament only happened on Photoshop.

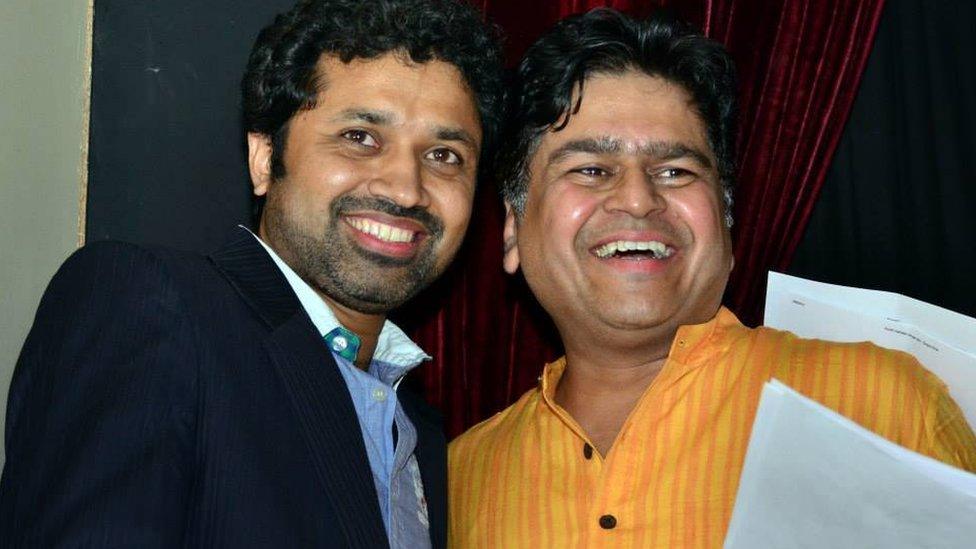

Shammas Oliyath, who runs the verification site Check4spam.com, external is another "warrior" in the battle against fake news.

His content is divided into several categories such as "internet rumours" and "promotions", but he says most of the news he deals with tends to be politically related.

India has more than a billion active phone connections

He gets about 200 WhatsApp inquiries a day, a number that has picked up after he got a little publicity for forcing a media organisation to retract a story which claimed that the assets of wanted Indian gangster Dawood Ibrahim had been frozen.

Despite their best efforts however, all three men know that they simply cannot take on the exploding fake news system on their own.

Mr Sinha says Altnews has done roughly 3.2 million pageviews in five months, while SM Hoaxslayer gets about 250,000 pageviews a month. Mr Oliyath says Check4spam.com gets about 15,000 hits a day.

These numbers pale in comparison to mainstream media sites, and hardly make a dent in the hundreds of thousands of messages that get passed around every day.

Mr Oliyath rues the fact that India's mainstream media is a part of the problem.

"In the rush to report first, there is no focus on fact checking," he says.

Ms Raghunath agrees.

"Television in this country has always been tabloid and not serious. The state operated Doordarshan never took off, and the rest was always tabloid - which is to say, talking heads and live news reel," she said, adding that there is very little emphasis on process even in India's digital news ecosystem.

Shammas Oliyath (left) shot to prominence after forcing a media organisation to retract a story

What this means is that, a lot of the time, social and mainstream media feed off one another, fuelled by the desire for more eyeballs.

However, she says the larger issue is still one of media literacy and believes that the fight against fake news still needs to be led by mainstream legacy media.

"People segment organisations into those they trust and those that they believe are there to entertain them. There is a higher onus on those that they trust to do more."

This, she says, could be as simple as breaking down an article and educating readers how they work.

"It can be as basic as distinguishing an opinion piece from a news piece and breaking down articles and identifying things like sources, fact and analysis," she says.

As important, she says, is making the truth go viral.

"We have to tackle this issue in a fun way, If people are consuming listicles, we need to do listicles, and if its memes, we need to do memes too. It's really important that we are not weird or academic about it".

BBC Reality Check is also dedicated to verifying news and debunking myths