I am 70: The woman as old as independent India

- Published

As India and Pakistan celebrate 70 years since their creation as sovereign states, the BBC's Geeta Pandey meets ceramic artist Meena Vohra, who was born a week before independent India.

On 7 August 1947, exactly a week before the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan, as murderous mobs went on the rampage in the city of Rawalpindi and surrounding villages, Shakuntala Mehta, a mother of three boys, went into labour and delivered her first baby girl.

The baby was named Meena, but there was no time for celebration.

Rawalpindi - which became part of the new nation of Pakistan - was among the cities worst hit by violence. Her husband, Subedar Ram Lal Mehta, a member of the British army, was busy fighting off armed rioters on the streets and trying to protect civilians from the mobs. He had had little time for his wife or children.

A week later Mrs Mehta fled with her children, including the tiny infant, to India where a sprawling refugee camp in the capital, Delhi, was to be their home for the next two years.

"I have no memory of the camp, but my mother and brothers told me later we were very poor and even to get one meal a day we had to struggle," Ms Vohra said.

"Until my father arrived in Delhi in November, my mother looked after us on her own. My eldest brother, who was 12, would find work and bring some money home on which we survived."

As she and her nation enter their eighth decade, Ms Vohra told the BBC that her journey had been much happier and more peaceful than that of India, which has seen wars, political assassinations, religious riots and murders.

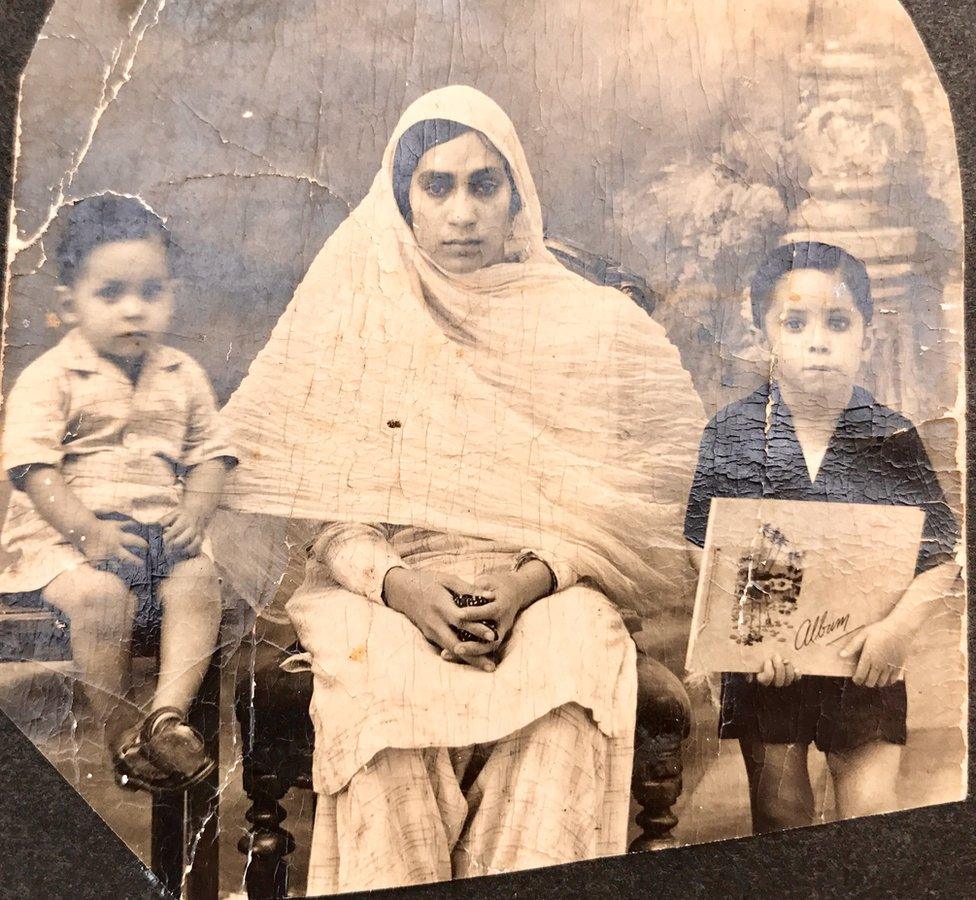

Meena Vohra's mother with two of her oldest children

These 100-year-old locks were the only souvenir the family brought back with them from Rawalpindi

Life for Ms Vohra really began when the Indian army allotted her father a "nice new" house in the cantonment town of Mau.

"Dad had been rewarded for bravery for his role in the fighting in Rawalpindi and he had become a lieutenant."

Over the next few years, as he moved across India from one posting to another, the family made their home in new towns and cities every few years.

Partition of India in August 1947

Perhaps the biggest movement of people in history, outside war and famine.

Two newly-independent states were created - India and Pakistan.

About 12 million people became refugees. Between half a million and a million people were killed in religious violence.

Tens of thousands of women were abducted.

Read more:

In 1967, after she graduated from college, 20-year-old Meena married a young air force officer her parents chose for her.

"Flight-Lieutenant Gurjinder Kumar Vohra was 26. Before the wedding, I had met him just once with the rest of my family. The army band played at our wedding and his family was very impressed," she laughs.

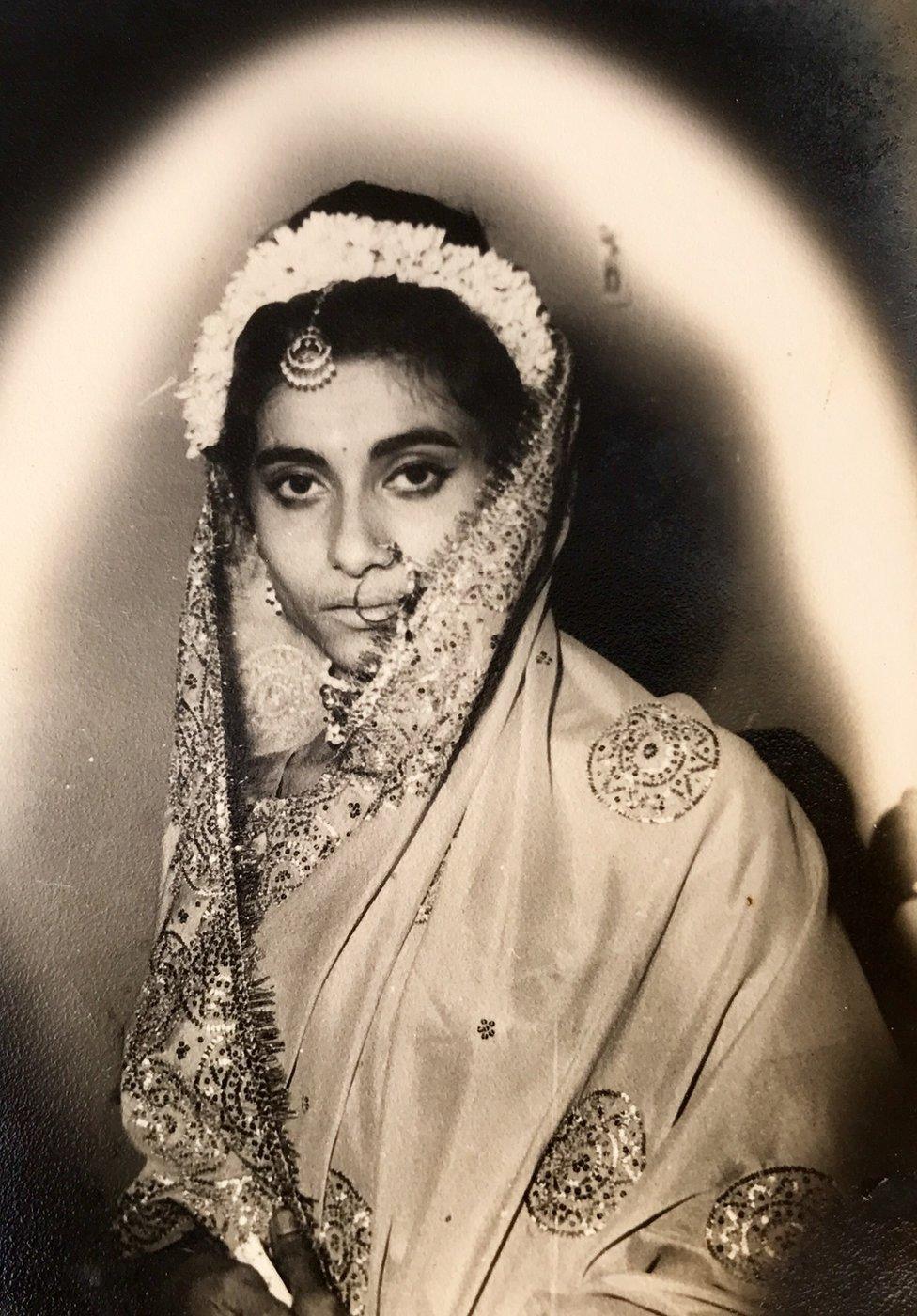

In 1967, 20-year-old Meena married a young air force officer her parents chose for her

The wars of 1962 and 1965, external, with China and Pakistan respectively, caused only minor disruption to her life. "My father didn't go to war. In the cantonment where we lived, we had to run and take shelter in the trenches every time a siren would go. We never had any time to take anything with us, except perhaps a bottle of water."

But war did enter her home in 1972 when her air force engineer husband was sent to Bangladesh - then fighting for independence from Pakistan - to repair the aircraft and machinery being used there.

"He was there for a month-and-a-half and I was really scared for him. He was in the midst of war. I had small children to look after. I had to take them and run into the trenches whenever the siren would go," she says.

"But the children would get excited every time they would see a fast plane dashing across the sky and shout: 'That's Papa'.

"After the war, he returned home to a hero's welcome and the air force organised a big gala celebration. It was a proud moment for us," she adds.

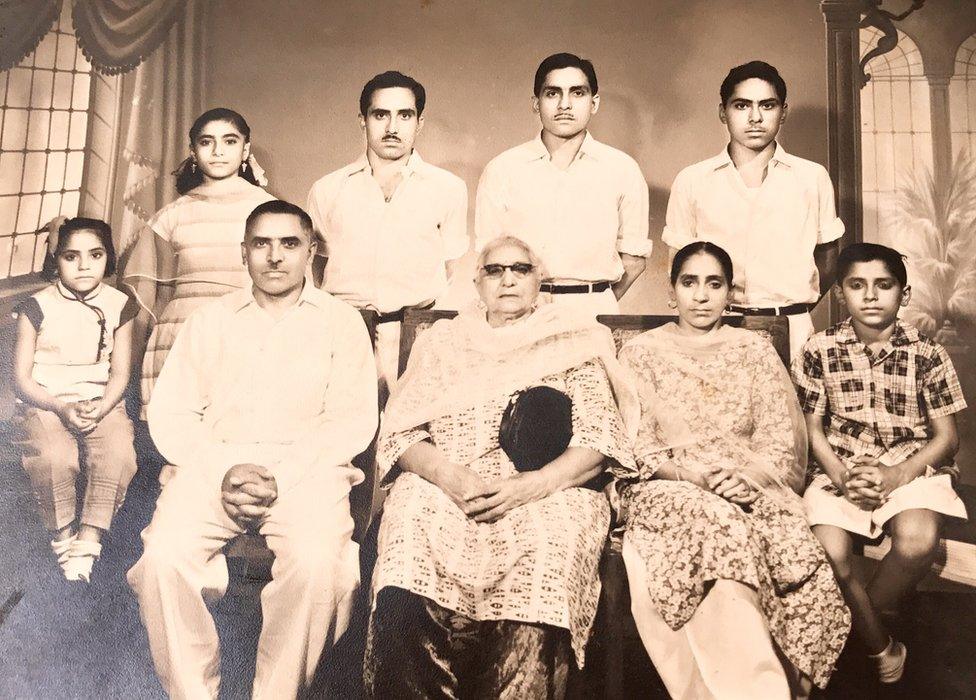

Meena Vohra (rear left, standing) with her parents, siblings and grandmother

Meena Vohra spent the 1970s and 1980s giving birth to three children and raising them. In 1980, she also set up a school for underprivileged children in a village in south Delhi.

"I started with one four-year-old child in a small hut. People weren't keen on sending children to school because they wanted them to work. But gradually we persuaded the villagers. We collected funds and built four rooms.

"Two-and-a-half years later when I left to teach at the Naval Public School, we had seven teachers and 40 students."

The darkest hour in the nation's life, Ms Vohra says, came on 31 October 1984 when then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards for ordering the army into the Golden Temple, Sikhism's holiest shrine.

"I adored her. She was strong and determined, a forceful orator, she carried herself really well, the saris she wore and the way she wore them. She was very charismatic and dignified. I wanted to be like her. I was heartbroken," she says.

Ms Vohra's father Subedar Ram Lal Mehta was a member of the British army

"I was in the school when she was shot. The school was shut and we were sent home in school buses. We were glued to our tiny black-and-white TV set watching news. We even forgot to cook or eat."

Then the anti-Sikh riots started. "It was horrible. Our neighbours were Sikhs and they were too afraid to step out so we helped them get supplies. The air force campus was guarded and secure, but then you never know.

"It took a couple of months to get back to normal life. But there was fear, many of our friends shifted to Punjab because they felt insecure in Delhi."

In 1997, when she turned 50, she decided to do something different: "I bought a potter's wheel and began working with clay."

A year later, she opened a studio to teach pottery and over the past two decades, she has taught 400-500 students.

In 1997, when she turned 50, Ms Vohra bought a potter's wheel and began doing pottery

Earlier this year, she celebrated her 50th wedding anniversary

As she turns 70, she reflects on her life and that of India.

"In my personal life, I'm a very peaceful, happy soul, contented with what God has given me. I couldn't have asked for more," she says.

On the other hand, she says, the journey of India has been "bittersweet".

The country has made immense progress, in the field of electronics, information technology, industry and space. In the past decade, there have been revolutionary changes with mobile phones and new technology, she says.

"But I despair about the current political situation, the climate of intolerance, the growing Hindu fanaticism and the government backing it. I'm bothered when Muslims are lynched by mobs. And since no-one is being punished for these crimes, they continue.

"Muslims are feeling very insecure and agitated, and that's not good for the country.

Medals Subedar Ram Lal Mehta was awarded during his army career

Ms Vohra has won several awards for her paintings and pottery

"And I worry about the loss of individual freedoms. How can the government dictate what to eat, what to wear and where to go?" she asks.

For someone whose family lived through the trauma of partition and after her personal experiences of the 1984 riots, Ms Vohra says hatred against "the other" must be shunned.

"I first became aware of partition when I was six or seven years old. I studied about it in school and our family elders told us stories of the carnage and the blood-letting that accompanied it.

"I was very disturbed and I said I would never be friends with a Muslim, but then I met lots of Muslims in the armed forces, who worked with my dad and my husband, and we made lots of good friends and I realised how wrong I was to think like that."

I asked her where she planned to be on 15 August.

"Every year I visit the school I set up in Delhi for underprivileged children to hoist the flag on India's independence day. That's where I will be this year too."