Are the Rohingya India's 'favourite whipping boy'?

- Published

The Rohingya are described as the world's 'most friendless people'

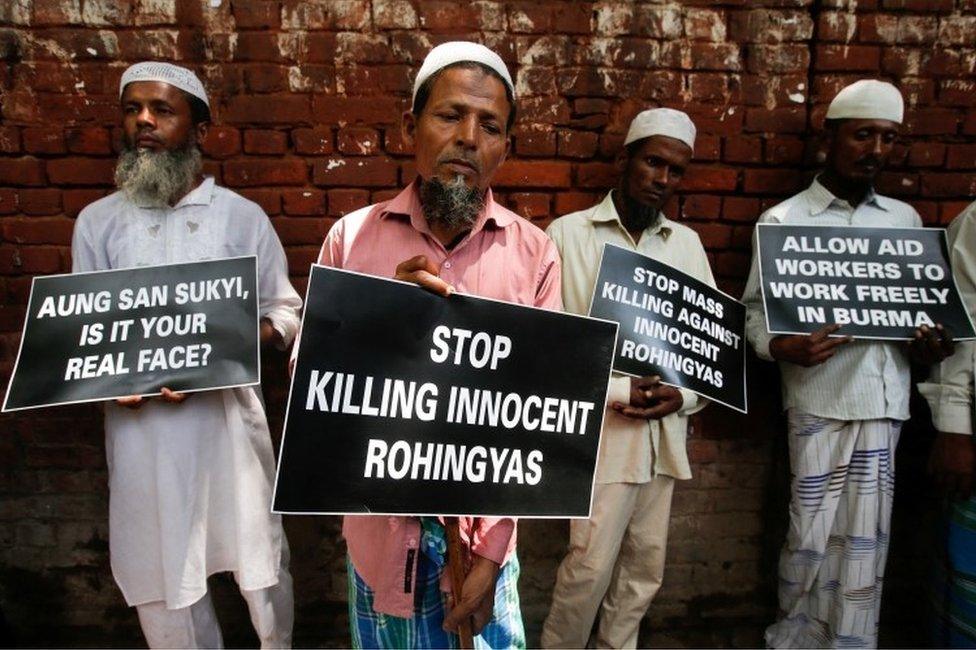

At home in Myanmar, they are unwanted and denied citizenship. Outside, they are largely friendless as well. Now the government says that Rohingya living in India pose a clear and present danger to national security.

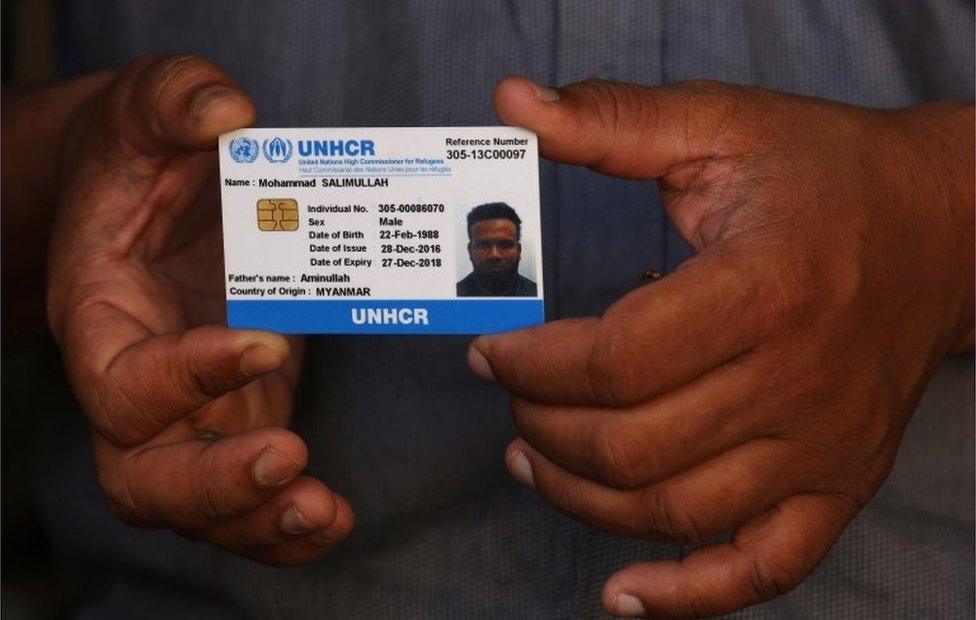

First, a government minister kicked up a storm earlier this month when he announced that India would deport its entire Rohingya population, thought to number about 40,000, including some 16,000 who have been registered as refugees by the UN.

The Rohingya are seen by many of Myanmar's Buddhist majority as illegal migrants from Bangladesh. Fleeing persecution at home, they began arriving in India during the 1970s and are now scattered all over the country, many living in squalid camps.

The government's announcement has come at what many say is an inappropriate time, as violence in Myanmar's western Rakhine state has forced more than 400,000 Rohingya Muslims across the border into Bangladesh since August.

When petitioners went to the Supreme Court challenging the proposed ejection plan, Narendra Modi's government responded by saying it had intelligence, external about links of some community members with global terrorist organisations, including ones based in Pakistan.

It said some Rohingya living here were indulging in "anti-national and illegal activities", and could help stoke religious tensions.

Most Rohingyas in India live in squalid camps

Experts agree the threat from Myanmar's newly-emergent Rohingya militant group, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (Arsa), should not be underestimated. Analyst Subir Bhaumik describes Arsa as "strong and motivated", although its exact size and influence remain unclear.

The current crisis began in Rakhine in August with an Arsa attack on police posts which killed 12 security personnel. Reports say the group has at least 600 armed fighters.

Bangladeshi officials claim that Arsa has links with a banned militant group Jamaat-ul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB), external, which was held responsible for the July 2016 cafe attack in Dhaka in which 20 hostages died. Delhi believes groups like Arsa pose a threat to regional security.

But critics of the move wonder how much credible intelligence India has on Rohingya refugees on its soil with terror links.

They say India has fought long-running home-grown insurgencies with rebel groups in the north-east and Maoists in central India, which have arguably posed a greater threat to national security than what they say is a rag-tag and scattered Rohingya population.

Also, many question a proposed move to punish a community for the perceived crimes of some - in other words, is it right to consider all Rohingya a security threat?

Watch: Who are the Rohingya?

On the other hand, India's Home Minister Rajnath Singh insists Rohingya are not refugees or asylum-seekers. "They are illegal immigrants, external," he said recently.

But critics say this is untenable because India is legally bound by the UN principle of "non-refoulement" - meaning no push-backs of asylum seekers to life-threatening places.

Also, India's constitution clearly says that it "shall endeavour to foster respect for international law and obligations in the dealings of organised peoples with one another".

Like much of Asia, which is home to a third of the more than 20 million displaced people in the world, India has a curious track record in refugee protection.

Although the country is not party to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention and its 1967 protocol and doesn't have a formal asylum policy, it hosts more than 200,000 refugees, returnees, stateless people and asylum seekers, according the UN refugee agency, UNHCR. (These include more than 100,000 Tibetans from China and more than 60,000 Tamils from Sri Lanka.)

The Rohingyas are thought to number about 40,000 in India

At the same time, India has always taken in refugees based on political considerations. It took in tens of thousands of refugees from Bangladesh during the country's 1971 war of independence from Pakistan even as it trained and supported pro-liberation guerrillas, for example.

Many like Michel Gabaudan, former president of the advocacy group Refugee International, believe that India distrusts the international refugee process partly "because it [has] received little recognition for taking in refugees" in the past.

'Unenviable'

A 2015 paper, external by a group of Indian researchers said the image of Rohingya in India was "unenviable - foreigner, Muslim, stateless, suspected Bangladeshi national, illiterate, impoverished and dispersed across the length and breadth of the country".

"This makes them illegal, undesirable, the other, a threat, and a nuisance," the paper said.

This also makes them, says analyst Subir Bhaumik, "a favourite whipping boy for the Hindu right-wing to energise their base".

"Remember how the issue of the Bangladeshi illegal migrant was invoked by Mr Modi and his party during the 2014 election campaign?" he said, referring to the prime minister's efforts to generate support from his Hindu base in areas with many migrants.

In Myanmar, Rohingya are seen as illegal migrants from Bangladesh

In the end, many say, what is is deeply troubling is a country talking about returning Rohingya people to Myanmar even as they appear to be the target of what the UN says "seems a textbook example of ethnic cleansing".

"Any nation has a right, and indeed a responsibility, to consider security risks, but that cannot be confused as an excuse to knowingly force an entire group of people back to a place where they will face certain persecution and a high likelihood of severe human rights abuses and death," Daniel Sullivan of Refugees International told me.

That is something India would possibly do well to remember.