Has Mumbai become India's most unliveable city?

- Published

People say the stampede that killed 23 people on Friday was an accident waiting to happen

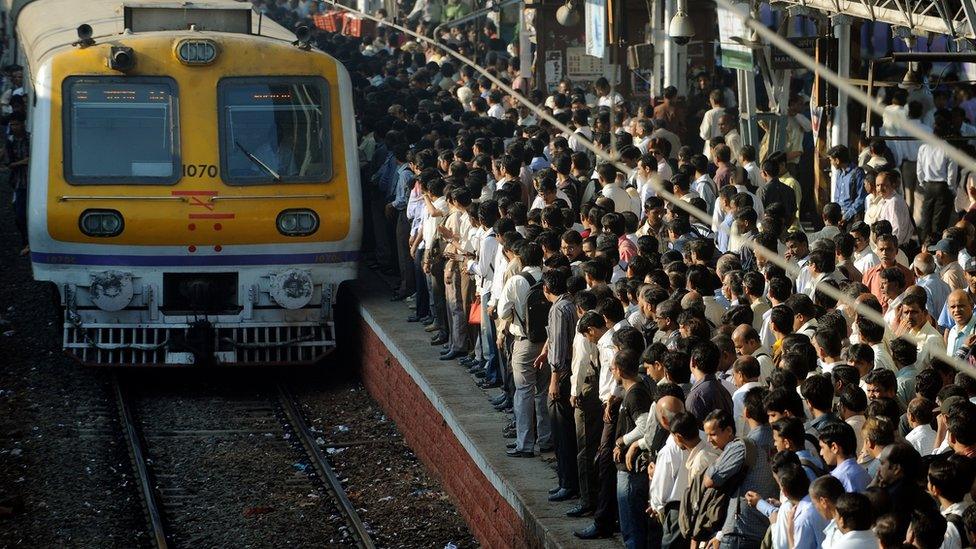

A deadly stampede at a busy Mumbai station that killed 23 people last Friday has caused anger, not only because it could have been avoided, but because residents feel that it is yet another example of the city suffering due to officials' apathy, writes the BBC's Ayeshea Perera.

The feeling is overwhelming. The stampede at Mumbai's Elphinstone Road railway station was an accident waiting to happen.

The stairway leading out of the station into a busy office district in central Mumbai was far too narrow to handle the thousands of passengers who used the station every single day. Daily commuters spoke of how it would unnervingly shake every time a train pulled in or out of the station.

Mumbai, with a population of roughly 22 million, is the world's fourth most populated city. And population has been its nemesis. Surrounded by water on three sides, the city has no space to expand. And the result is an enormous pressure on public services.

There had been a number of petitions to civic authorities, asking for Elphinstone bridge to be renovated, but to no avail.

"The foot overbridge and staircases are cramped, and the station was always at risk of a stampede. We often brought this up, but railway authorities ignored our concerns," Subash Gupta, a member of Mumbai's railway passengers' association told BBC Marathi.

A report said Mumbai's residents showed an unusual "willingness to put up with inconveniences for a livelihood"

In a twist of irony, one newspaper reported that the long overdue funds to renovate the station bridges had been granted on the same day as the deadly accident. Another quoted the former minister of railways Suresh Prabhu as saying he had allocated 120m rupees ($1.8m;£1.3m) towards boosting the infrastructure in 2015, external and did not know why it had not been used. Public documents accessed by a television channel, external show that of that sum, a meagre 1,000 rupees had been set aside for the repairs.

And it's not just the railways that are the problem. A few weeks ago, heavy rains caused severe flooding, stranding tens of thousands of residents as roads literally turned into rivers. A few days later, a residential building collapsed, killing more than 30 people. The crumbling infrastructure of India's financial capital seems to be breaking down all at once.

The Mumbai Human Development Report, external of 2009, noted that a "willingness to put up with inconveniences for a livelihood" appear to be among the unique features of the city's residents.

So inconveniences like cramped and unhygienic housing, diminishing open space and crowded train travel are accepted as part and parcel of daily life.

But now people have just about had enough.

The anger is palpable. Fed up residents are being vocal about how much they feel their city is suffering due to political and official apathy.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

"Everything has gone wrong. Politicians either don't understand or they don't care. Mumbai pays a bulk of India's taxes, but it gets nothing back," senior urban planner Chandrashekhar Prabhu told the BBC.

The problem, according to Mr Prabhu, is that Mumbai is being "slowly strangled" by politicians and corporate lobbies who treat the city as a "milking cow" and have no sense of responsibility towards its people.

"We only notice when a stampede kills 23 people in one go. But about eight to 10 people die every day in stations due to issues like unsafe crossings and overcrowding. It's become so normal, no-one talks about it. It's like these deaths mean nothing".

Mumbai's train system, according to a 2010 estimate by the World Bank, suffers from some of the most severe overcrowding in the world, carrying 4,500 passengers in trains with a rated capacity of just 1,700.

It funded a project to increase the number of carriages from 9 to 12 in an effort to decongest the lines, but the project took so long that, by the time it was implemented, it did very little to change the situation.

Naresh Fernandes, the editor of Indian news portal scroll.in and an author of several books on the city, said the lack of planning in Mumbai could only be described as "criminal".

Some urban planners believe Mumbai's infrastructure is in serious trouble

"Mumbai has had so many wake up calls and yet it's as if these things don't sink in," he told the BBC. "Take the terrible flooding the city saw in 2005. There was so much anger and yet officials continue to pass and enact policies that only exacerbate the issue."

The 2005 Mumbai floods, when the city received an unprecedented 944 mm of rain, killed some 500 people and brought the city to a complete halt. The airport was shut for more than 30 hours, offices and schools were closed and citizens were stranded in waist deep water across the city.

The biggest issue at the heart of everything, both Mr Prabu and Mr Fernandes say, is poor urban planning, driven by Mumbai's high real estate values and a powerful builders lobby that influences policy in the city.

The result is that money is sucked out of essential public infrastructure projects and pushed instead into things like clearing land for new housing projects, gated communities for the very rich and infrastructure projects that not everyone can use.

"Mumbai is being taken away from its people," said Mr Fernandes who described this as his "pet peeve". "It has given up on the notion of the public."

The 2005 floods were a "wake up call" that have not been heeded, says local journalist Naresh Fernandes

Mr Fernandes alleged that the railways suffered in particular because there was no money or kickbacks to be had from them any more. "This is why we end up with things like sea links and the upcoming coastal road, which are essentially vanity projects," he said.

Travel expert Sudhir Badami believes that part of the solution, at least, is a radical overhaul of the transport system. He is an avid proponent of introducing a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system to ease the congestion on the railways and give people another viable commuting option.

But Mr Fernandes says that Mumbai's citizenry also has to stand up and be counted. "It is a callous system. It is tempting to blame individuals and yes, we are being serviced very badly, but plastic is in the drains because someone put it there. We should also take some responsibility."