India's Indira canteen: The best meal you can buy for 13 cents

- Published

The governing Congress party in the southern Indian state of Karnataka recently set up Indira canteens in the state capital, Bangalore, which serve more than 200,000 cheap meals every day. The BBC's Geeta Pandey joins the queue to sample the treats and comes back more than satisfied.

It's just after 07:00 and a crowd has already begun to gather outside a squat building, located near the bustling City Market.

At 07:30, the gate is thrown open and the crowds rush in. There's some jostling but soon people fall into line, impatient bodies pressed into each other.

The queue moves quickly. Men and women walk up to a small window, hand over their money and receive one or two green plastic tokens, which are then exchanged at the counter for food.

They pick up their bright yellow trays and move to a table in the room or outside in the courtyard to eat.

I too buy my tokens and join the queue for breakfast. On the menu are idlis (savoury cakes traditionally eaten across south India for breakfast), pongal (a popular rice dish) and some coconut chutney.

The food is fresh, warm, flavourful and delicious. And the best part? Each dish costs a mere five rupees, so if you buy both you pay just about 10 rupees or 13 cents, which is as good as free.

Since they opened their doors on 16 August, the canteens named after Indira Gandhi - the Indian prime minister assassinated in 1984 - have been drawing in the crowds.

The idea is clearly borrowed from the hugely popular and successful Amma canteens, started by J Jayalalitha, the late chief minister of the neighbouring state of Tamil Nadu. I ate at one Amma canteen last year and the food was good. At Indira canteen, it's even better.

Geeta Pandey tried the food for herself

The customers at these canteens - which are like the soup kitchens of the West - are mostly poor people: daily wage labourers, drivers, security guards, beggars - who earn a few hundred rupees a day, sometimes not even that. And for them, every penny counts.

Mohd Irshad Ahmad, who works as a security guard at a Bangalore shopping centre, tells me he's a regular at the Indira canteen.

"The food is very good. Earlier, I used to eat in a nearby restaurant and would pay 30 rupees for breakfast. Now I'm saving 25 rupees. It's a good thing. They should extend this scheme to the rest of the state too."

Lakshmi, who comes every day to the market to buy fruit which she then sells outside a school, says the canteen has freed her from the daily drudgery of making breakfast. "I now no longer need to cook in the mornings. That makes my life so much easier. The food is cheap here so I can afford it. And this is very good food too."

Mohan Singh who lives in a lodge nearby comes to the canteen for all three meals a day. "I spend 40 rupees on three meals," he says. "Eating out is expensive. [Previously] I would spend about 140 rupees on food daily. For me this is a real blessing."

Economists say the canteens are a burden on the exchequer but they are a hit with politicians in a country where hundreds of millions of people live on less than a dollar a day.

Many analysts say the Amma canteen was one of the main reasons behind Ms Jayalalitha's success at the last elections.

In Karnataka, where elections are due early next year, the decision to set up these canteens is obviously a political one even though the authorities insist that their motives are more altruistic.

"Our chief minister decided to feed the poor," Manoj Rajan, the official in charge of the project, told me.

Since they opened their doors on 16 August, the canteens have been drawing in the crowds

A mother feeds her baby at the Indira canteen

"The canteens are aimed at the migrant population, cab drivers, students and working couples who have little time to cook. But, of course, they are open to every citizen."

After the chief minister announced the plan for the canteens in April, Mr Rajan's team worked day and night to turn the plan into reality.

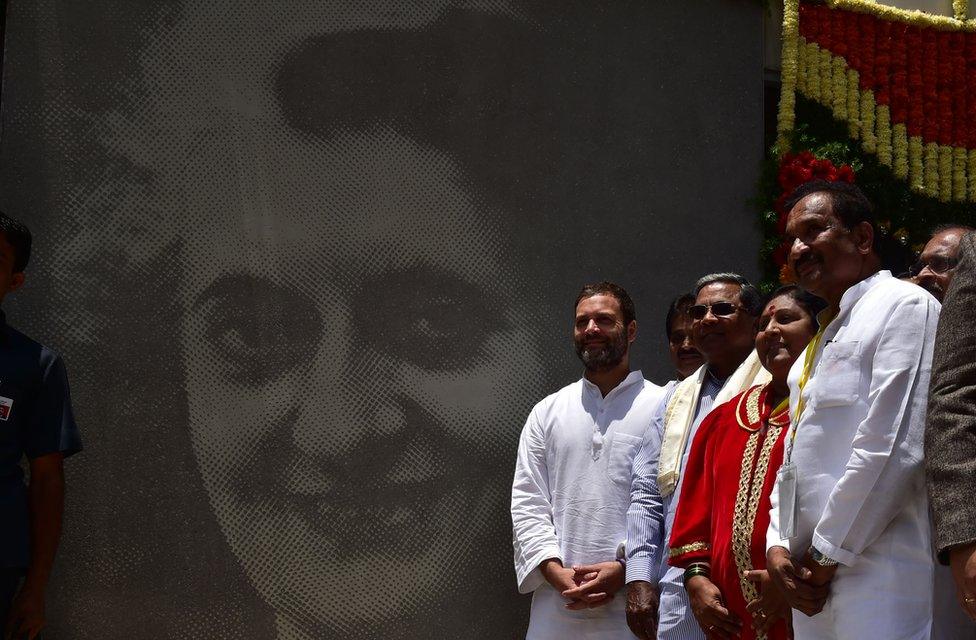

On 16 August, a day after India celebrated 70 years of independence from British colonial rule, Congress party vice-president Rahul Gandhi travelled to Bangalore to inaugurate the canteen to "free people from hunger".

Today, there are 152 canteens in the city, serving 200,000 meals daily. The plan, Mr Rajan says, is to grow to 198 canteens serving 300,000 meals a day by the end of November.

The scheme would then be expanded to cover the rest of the state by January, with more than 300 canteens in total.

The food is cooked in centralised kitchens from where it's distributed to nearby canteens

The canteens have water coolers, toilets and places for the elderly to sit down

As lunch time approaches and we begin to feel hungry again, we turn up at another Indira canteen for another meal. This time we dine in an upscale district called Markham road. Here, the crowd is thinner but the customers include office workers and school students.

The menu, consisting of piping hot rice and sambhar (lentils cooked with vegetables), does not disappoint.

The canteens were inaugurated by Congress party vice president Rahul Gandhi (first from left)

According to a popular saying, the way to people's hearts is through their stomachs. The Congress party is hoping it will also win them votes at election time.

Venkatesh, a fellow diner, tells me people are worried that these canteens would shut down if there was a change in government.

I ask Mr Rajan what would happen if the Congress party lost. "A citizen-centric project will continue, no matter who forms the government," he insists.

- Published4 July 2016

- Published15 December 2016