Photographs that show a bygone India

- Published

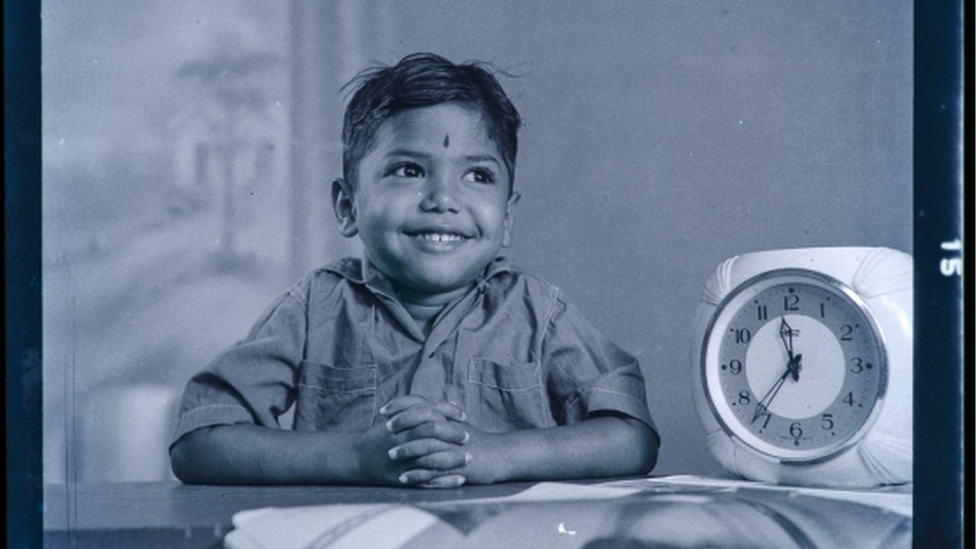

Many of the archival images are portraits of families and famous stars

There was a time an event would not begin without a photographer. "I remember the days when event organisers would even delay a show if the photographer was running late," says Balachandra Raju, a 78-year-old third-generation photographer of Sathyam studio, a still surviving photo studio in India's southern city of Chennai (formerly Madras).

"Now, all you need is a phone that fits in the palm of your hand to take a photo."

Photo studios are on the verge of extinction in the digital era. But as they struggle to keep theirs shutters open, one research project is looking at ways to preserve their legacy by digitising archival images.

The project, funded by the British Library, visited around 100 photo studios across the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu and preserved, or rather digitised, 10,000 prints. Many of the photos were taken between 1880-1980, and they ranged from portraits of families and famous stars to weddings and funerals.

Many would flock to studios to get portraits done, which were popular at the time

Zoe E Headley, one of the researchers, said this is the first project of its kind done in India. "The digital archive will be an asset for those interested in history - what life was like in 19th Century Tamil Nadu."

Ramesh Kumar, another researcher on the project, called it a "gold mine" for photographers. "The research we've done also highlights production techniques used before digital photography arrived in our cities and towns," he said.

Often, they would find old photos stacked on top of one another in the attic of a studio, or stashed away in a cupboard. "No one had bothered to clean them," Kumar said, adding that many photos had deteriorated due to the "tropical climate and humidity" in Tamil Nadu.

The researchers don't have exact statistics on the number of studios still operating in the city, but according to Headley, "the digital revolution has spelled doom for photo studios across the world."

Sathyam Studio has remained in the same spot since 1930

Sathyam Studio, located on RK Mutt Road in Chennai, has been in the same spot since it opened in 1930. At first glance, it looks like a small photocopy shop rather than a photo studio. Inside, portraits of Hemamalini, a famous Tamil film star, and VV Giri, former president of India, grace the reception walls.

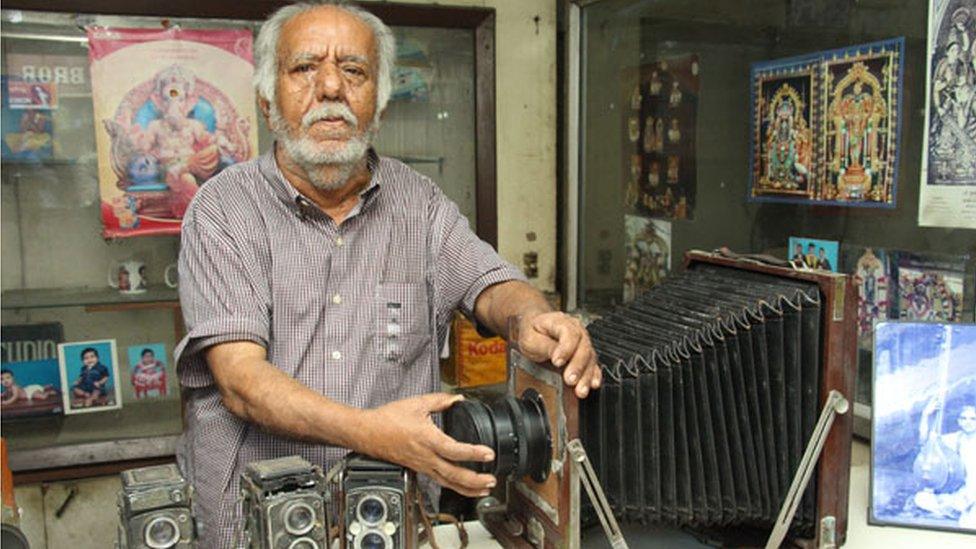

The studio is run by Anandh Raju, who took it over from his father. Mr Raju's grandfather founded the studio during British rule, and even designed a daguerreotype camera, which is now covered in cloth and kept away. One of the earliest forms of photography, the daguerreotype process used iodine-sensitised silver plates and mercury vapour to make images.

Balachandra Raju with the daguerreotype camera made by his grandfather

"This business has lost its sheen," said Mr Raju, "My grandfather, when he built this studio, used to live like a king." The studio's darkroom, which was once littered with shots of glamour and glitz, is now used as a storage room, he added.

Nallapillai studio, in central Tamil Nadu, has suffered a similar fate.

Its proprietor Ranganathan, who uses only one name, said he spends about 20,000 rupees (£230; $310) each month to run the studio that was founded by his great grandfather almost 150 years ago.

To survive in this digital era has been a struggle. "Many customers don't book us for special events anymore," he said, adding that they have all got smartphones to do the job.

"I'm not sure if photo studios will exist five years from now," he told BBC Tamil.

A portrait shot of a member of Hyderabad's royal Nizam family

Portraits like this one were regularly taken at photo studios in Tamil Nadu

But this is why, according to Mr Raju, this archival project is so important.

"I don't know if this project will help my studio," he said, "but when the researchers spent hours in my studio, I saw them get excited over all of these old photos, and it was like they had given these pictures a second chance."