The 24-year-old challenging Narendra Modi in his own state

- Published

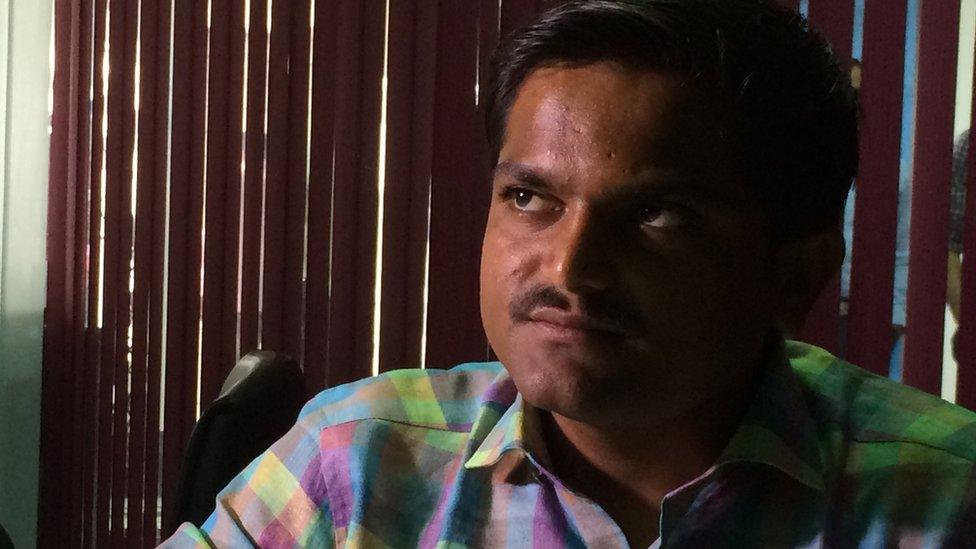

Hardik Patel enjoys massive support among his Patidar community

At a dusty crossroads in small town Gujarat, people are waiting patiently in the winter sun for a man many believe is giving India's powerful Prime Minister Narendra Modi sleepless nights.

Hardik Patel has a mild scowl and a slight stoop. A commerce graduate and son of a businessman, he is utterly middle-class. At 24, he is not even old enough to stand for election under India's rules.

Yet, in less than two years, Mr Patel has become, in the words of one observer, Mr Modi's "tormentor-in-chief".

He is the face of massive caste protests which have rocked the prime minister's home state - which goes to polls on Saturday - and is leading a movement demanding that the Patels - or the Patidar caste - be given better access to jobs and education through the quota system.

'Patels feel left behind'

Some 14% of people in Gujarat are Patels, a socially privileged, influential farming community which has traditionally voted for Mr Modi's BJP, that has ruled Gujarat for more than two decades. In the past the community has fought violently against affirmative action, believing that merit should the sole determinant for college seats and government jobs.

But things have changed.

India is in the throes of massive churn and tilling the land is increasingly being seen as a back-breaking, unprofitable profession, that is less prestigious than others.

A number of landowning castes - Jats in Haryana and Marathas in Maharashtra, for example - are in ferment because they feel they lack the means to educate themselves and get professional jobs.

The Patels are demanding affirmative action for the community

Quality state-run professional colleges are too few, and their mushrooming private counterparts too expensive for most people. Declining farm incomes are pushing community members into cities, where the lack of jobs has made competition for them intense. Some 48,000 small and medium factories, many owned by the Patels, have shut in Gujarat in the face of competition from cheaper Chinese imports.

Anxious about their future, they have taken to the streets to demand affirmative action, even though there is little scope to extend quotas. "The Patels feel left behind," says lawyer Anand Yagnik. He says most of them support quotas.

In 2012, the BJP won 115 of Gujarat's 182 seats under Mr Modi's leadership. Two years later, he stormed to power in Delhi with a general landslide, and Gujarat has since been ruled by politicians who lack his stature. So the BJP no longer looks invincible in the state. Under fire from Mr Patel's community, which is threatening to desert it in droves and damage its prospects for a sixth outright win, Mr Modi's party is suddenly on the back foot.

The Patels can influence the ballot in some 70 seats, where they are considerable in number. The BJP appears to have bungled in its efforts to placate the community with its strong arm tactics.

Twelve community members died , externalafter police fired on Patel demonstrators two years ago. Mr Patel himself was charged with sedition and jailed for nine months, and then, according to his bail conditions, told to remain out of the state for six months.

Mr Modi has held more than two dozen public meetings in the run-up to the elections

Imprisonment and exile made him a hero in Patel eyes. In the small town of Talala, supporters call him a messiah and gift him framed pictures of Asiatic lions whose last abode is the nearby Gir forest. "He's the real lion among us," one of them told me.

"The BJP is facing its toughest election since 2002. The threat from Hardik Patel is serious. He's the biggest story of the Gujarat elections," says Uday Mahurkar, a senior journalist and author of a book on Mr Modi's government.

So when Mr Patel arrives three hours late in a silver SUV at the crossroads, his supporters surge forward to get a glimpse of him. Many are young men on motorbikes, with smartphones and sunglasses, and wear tee-shirts emblazoned with pictures of their leader. If they have jobs, they tend to be low-paid. Some have no job at all.

Youth uprising

First-time voter Bhavadib Maradia, 19, says he doubts he'll get a job in the private sector after he graduates, and to qualify for a government job he will need a quota.

Kirti Panara, a 42-year-old small plastic goods trader, says he wants his daughter to become an engineer or doctor and escape small-town drudgery. The only sugar factory in the area has been shut for years, and telecoms adverts around the town square promising a "digital life" somehow ring hollow for the locals.

Mr Patel waves out of the car sunroof, and then comes out to meet his supporters. Women smear vermillion on his forehead, offer him sweets and pose for selfies. It's a rag-tag army of fans without a party, but the outpouring of support is remarkably spontaneous. "Brother Hardik, march ahead, we are with you," they shout out in unison.

After urging supporters to vote the BJP out, Mr Patel's untidy motorcade weaves its way through the throngs lining the narrow roads.

A resurgent Rahul Gandhi has helped the Congress to stitch up a coalition with Mr Patel

At a packed public meeting in nearby school grounds, Mr Patel, in his trademark checked shirt and denim, is blunt about taking on Mr Modi and his BJP: he talks about farming in distress, the lack of jobs and the urban-rural divide. When he seeks affirmation from the young audience, a sea of hands clutching mobile phones goes up in the air.

Last month, Mr Patel announced a tie-up with the Congress party, which last won an election in the state in 1985, but has consistently picked up more than 30% of the popular vote in state elections.

Led by a resurgent Rahul Gandhi, the Congress has also stitched up an alliance with two other newer, electorally untested leaders - Alpesh Thakor, a 40-year-old leader of a grouping called the OBCs (Other Backward Classes) which fall between the traditional upper castes and the lowest; and a 36-year-old Dalit (formerly untouchable) leader, Jignesh Mevani, who is running as an independent. They are all united in their resolve to defeat the BJP.

Urban vote

It's a rainbow alliance of disparate bedfellows: affirmative action beneficiaries (OBCs and Dalits) and aspirants (Patels) who have had an adversarial relationship in the past. The BJP hopes that the alliance votes will not easily transfer to the Congress and believes that Mr Modi's undisputable charisma - he held more than two dozen public meetings in the run-up to the election - will see the party through when results are declared on 18 December.

Gujarat is a highly urbanised state, and the BJP enjoys the overwhelming support of the urban middle class. Five years ago, the party won 71 of the 84 seats in big cities and smaller towns.

This time, the 98 rural seats could cause a headache to the party. Many villagers say they are not happy with last year's controversial currency ban which squeezed incomes and cut crop prices. "Development is about the development of youth and farmers, of villages. It should not be lopsided in favour of cities," Mr Patel told me.

The BJP is also coping with an inevitable anti-incumbency factor after ruling uninterruptedly for more than 20 years. Whether it will be able to triumph over caste and identity with its talk about development and muscular Hindu nationalism remains to be seen.

When it comes to funds and mobilising voters, the BJP has a clear advantage. But it's not having an easy time - one leading opinion poll found a narrowing gap between the BJP and Congress, external that could even lead to a close finish. However urban votes could still tilt the vote in favour of the BJP. "The evidence so far seems to suggest that while the going may be tough for the BJP, the party will still scrape through and form the next government in Gujarat," says Sanjay Kumar, a pollster who has conducted three rounds of polling in the state.

Mr Patel believes the time to defeat the BJP is now.

"If things don't change this time, it will mean that the people of Gujarat are powerless against the BJP," he says.

- Published26 August 2015

- Published23 February 2016